Key Points

- What employers and job seekers want diverged briefly in the pandemic, but have come closer in recent months.

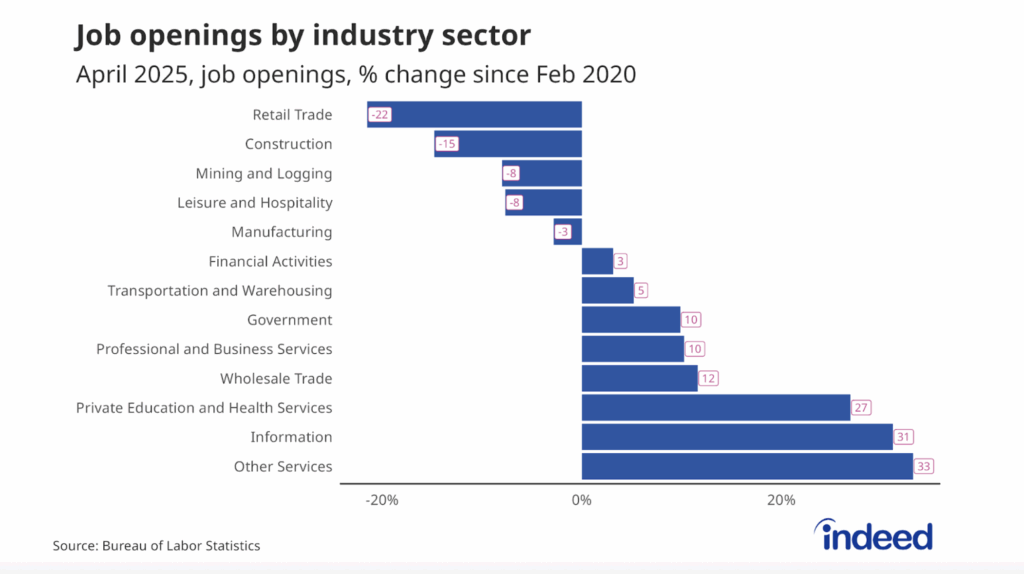

- Differences between sectors where employers have jobs to fill and the ones where job seekers are searching are below pre-pandemic levels, suggesting the mismatch does not explain the recent increase in hiring difficulties.

- Although lower than pre-pandemic, substantial occupational mismatch still exists, notably in sectors like nursing, food preparation & service, and management, where employers have a harder time than average attracting job seekers, and administrative assistance, customer service, and loading & stocking, which show more-than-average competition among job seekers.

Hiring is hard right now. Labor demand is strong, with employers expressing greater urgency in hiring and showing more willingness to offer recruitment incentives. At the same time though, total employment is still below pre-pandemic numbers. What then is holding back employment growth?

The labor market has clearly tightened substantially since mid-2020 as the economy has recovered from the initial pandemic shock. But there’s a sense that something else is going on in the economy. One big question is whether mismatch explains the difficulties employers are having staffing up, that is, whether there’s been a wholesale shift in the labor market so that occupations job seekers are interested in no longer match jobs on offer.

In order to investigate this question, we turned to Indeed data on how job seekers are interacting with job postings. There haven’t been big changes in what job seekers are looking for relative to where employers are hiring. It turns out that occupational mismatch between job seekers and employers is substantial, but has generally been declining since 2017. The only exception was a brief uptick in the beginning months of the pandemic. This finding is consistent with an overall labor market tightening.

Trend in Occupational Mismatch Has Resumed Downward Trend

Indeed data allows us to identify job seeker interests based on the jobs they click on. These clicks give us a forward-looking measure of where job seekers want to go and what they want to do. If the pandemic caused large-scale rethinking of the occupations job seekers are looking for, then there would be a substantial shift in the types of jobs they’re clicking on.

The changes in the economy may also have affected employer needs and changed the sectoral distribution of job opportunities. If that were true, then the shares of job postings by sector would also change.

Indeed has developed a metric, tracked monthly, for measuring the mismatch between available jobs and job seeker interests. If economic trends moved job seekers and employers further from each other, we’d see a rise in our mismatch measure. Instead we’ve seen the mismatch measure quickly return to its long-run downward trend after a relatively small and brief rise from March to June 2020.

Mismatch rose at the start of the pandemic as job seekers and employers moved in opposite directions in sectors such as administrative assistance, where the share of postings decreased while the share of job seeker clicks increased. That made the sector more competitive for job seekers. Other sectors, such as driving, went in the opposite direction, becoming more competitive for employers as the share of job seeker clicks declined and the share of job postings rose. Since June 2020, mismatch has fallen, with the distributions of job seeker clicks and job postings becoming more similar. In other words, workers and employers got more in sync in 2021.

However, overall mismatch remains substantial and there’s plenty of room for improvement. Our mismatch measure is based on comparing the distributions of clicks and postings by occupational sector. In January 2022, the metric stood at just over 20%. This means 20% of job seeker clicks would have needed to move to other sectors to balance job seeker interests and employer needs.

Top Contributors to Mismatch

The 20% figure means job opportunities aren’t evenly distributed across the economy. As the table below shows, some large sectors, such as nursing, food preparation & service, and management, stand out as fields where it is particularly hard to attract job seekers. In others, such as administrative assistance and customer service, job seekers face stiff competition to find work because the share of job seeker clicks is greater than the share of postings.

The top contributors to mismatch on both sides of the ledger, such as administrative assistance on one side and nursing on the other side, have been notably stable over time, meaning we haven’t had major upheavals in the relative amount of competition by sector.

Why has occupational mismatch declined?

One interpretation of the overall decline in mismatch could be that employers in sectors that might otherwise be experiencing particular problems hiring are making their postings more attractive by offering higher wages, more remote work, or other incentives. This responsiveness to evolving labor market conditions could be pushing mismatch lower even as employers still feel a crunch. Taking expensive measures such as boosting wages and benefits to recruit the workers they need may feel like a crunch to them even if it is happening across a wide range of sectors.

This higher compensation story is consistent with the point that declining mismatch is due to jobs and job seekers moving toward each other. It contrasts with the pre-pandemic decline in mismatch. That was primarily driven by jobs coming back in sectors where job seekers were more plentiful, such as human resources and community & social service, as the economy continued its long, slow recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

Conclusion

Many people may be looking to change careers right now. But, for those career changes to create hiring difficulties, workers would need to be shifting away from the jobs that are currently on offer.

When we compare the share of clicks on Indeed job postings for different sectors with the distribution of job opportunities by sector, we find occupational mismatch is substantial. It is a persistent problem, one that makes it harder for employers to find the workers they need and for job seekers to land the positions they want. But it’s not new and it’s not getting worse. In fact, it has improved along with the tightening of the labor market and is lower today than it was pre-pandemic. The data show a relatively steady downward trend from 2017 through January 2022.

Indeed’s measure of occupational mismatch rose briefly at the beginning of the pandemic. But given the dramatic changes in other labor market indicators such as unemployment and labor market participation in March and April of 2020, the increase in mismatch was relatively mild. Mismatch is a long term challenge in our economy, but it does not explain why it’s recently become harder for employers to find workers.

Methodology

We measure occupational mismatch based on the difference in shares of job postings and job seeker clicks using the Duncan and Duncan dissimilarity index, a formula we’ve used in past research. Clicks allows us to focus on the forward-looking interest of job seekers rather than their past work experience. Clicks also capture the intensity of job seeker interest since a single job seeker may click on many different job postings. The difference in shares means that we’re comparing the distribution of job seekers and job postings rather than raw numbers. Zero mismatch does not mean there is an appropriate job seeker to fill every job posting. Instead, zero mismatch would mean that the relative difficulty of hiring or finding a job is the same across all sectors. By contrast, high mismatch means in some sectors it’s hard to hire, while in other sectors it’s hard to find a job.

Economywide mismatch is driven by large categories. The formula captures the aggregate differences in the shares of job postings and clicks by category. Furthermore, mismatch rises with more categories, which explains why mismatch is lower here, where we use 55 sector categories, compared with our past research at the normalized job title level of 6000+ categories.