This report looks at job switching trends from several angles. First, it considers job switching rates by industry. Second, the report examines how this practice affects total employment in different industries. Third, it looks at what job switching means for employers. Fourth, we compare trends in higher- and lower-paying industries. Finally, the report describes hiring patterns in six industry groups.

Key points:

- Workers are switching jobs at a 4.1% rate thanks to a strong economy, much higher than the 2.3% rate during the Great Recession.

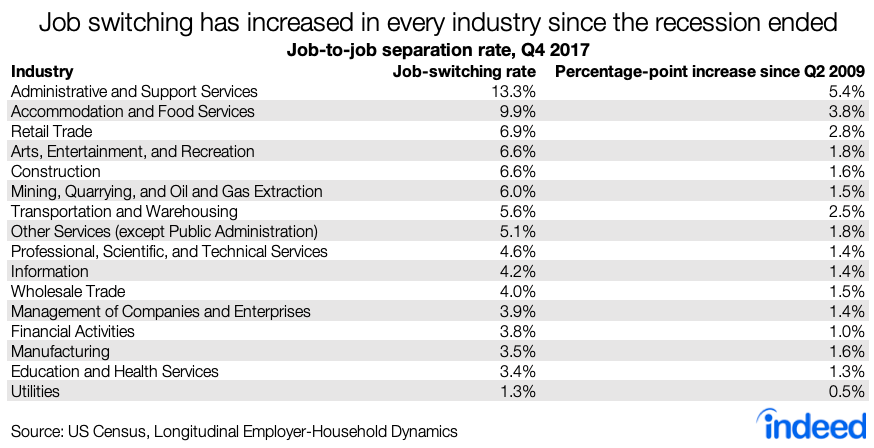

- The job switching rate is highest in the administrative and support services and accommodation and food services industries, and lowest in utilities, education and health services, and manufacturing.

- Workers usually leave their industries when they switch jobs, but the rate they jump to other industries hasn’t changed much in the past decade.

- In a tight job market, employers increasingly are hiring job seekers who are already working, as well as those who lack credentials previously demanded, such as a college degree.

- In addition, employers are adjusting recruitment strategies by offering more generous pay and benefits.

Introduction

These are good times for US job seekers. The unemployment rate is low, wages are rising, and, in some industries, jobs are going begging. But there’s one signal of a strong job market that isn’t getting the attention it deserves — the rising rate of job switching.

In the first three months of 2018, the most recent data available, about 4% of employed workers left their jobs for a position somewhere else, up from a job switching rate of just 2% in the third quarter of 2009, right after the depths of the Great Recession.

It’s common for job-hopping to climb as the job market tightens. A new position is often the best way to get a raise, escape a nightmare boss, or shorten a commute. Of course, finding work is hard in a downturn or when economic growth is weak. But when the economy is strong and jobs are plentiful, workers can more readily find that better opportunity they’ve been dreaming about. They might even be sought out by prospective employers.

Yet good times for workers are challenging for employers. Hiring managers today are finding it tough to bring on the employees they need, especially in industries where competition for workers is stiff.

The right strategy for attracting workers varies by industry. Some employers find they must raise pay and other forms of compensation, while others are going after groups they might have overlooked in the past, such as those who have been out of work for a long time, or lack the education or experience formerly demanded. One thing is clear though — when unemployment is low and the pool of jobless workers is small, it is especially important to recruit staff from the ranks of those already holding jobs.

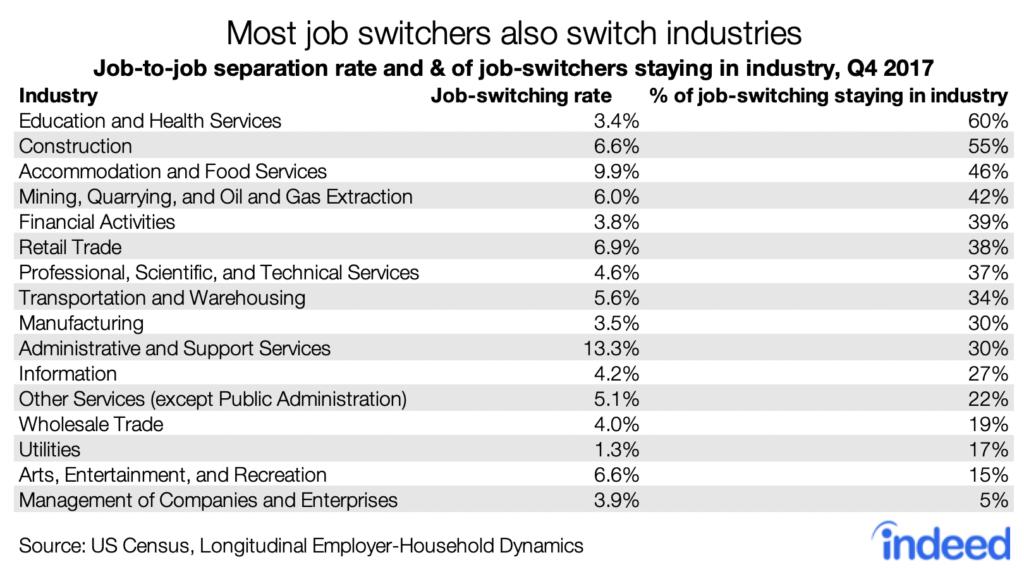

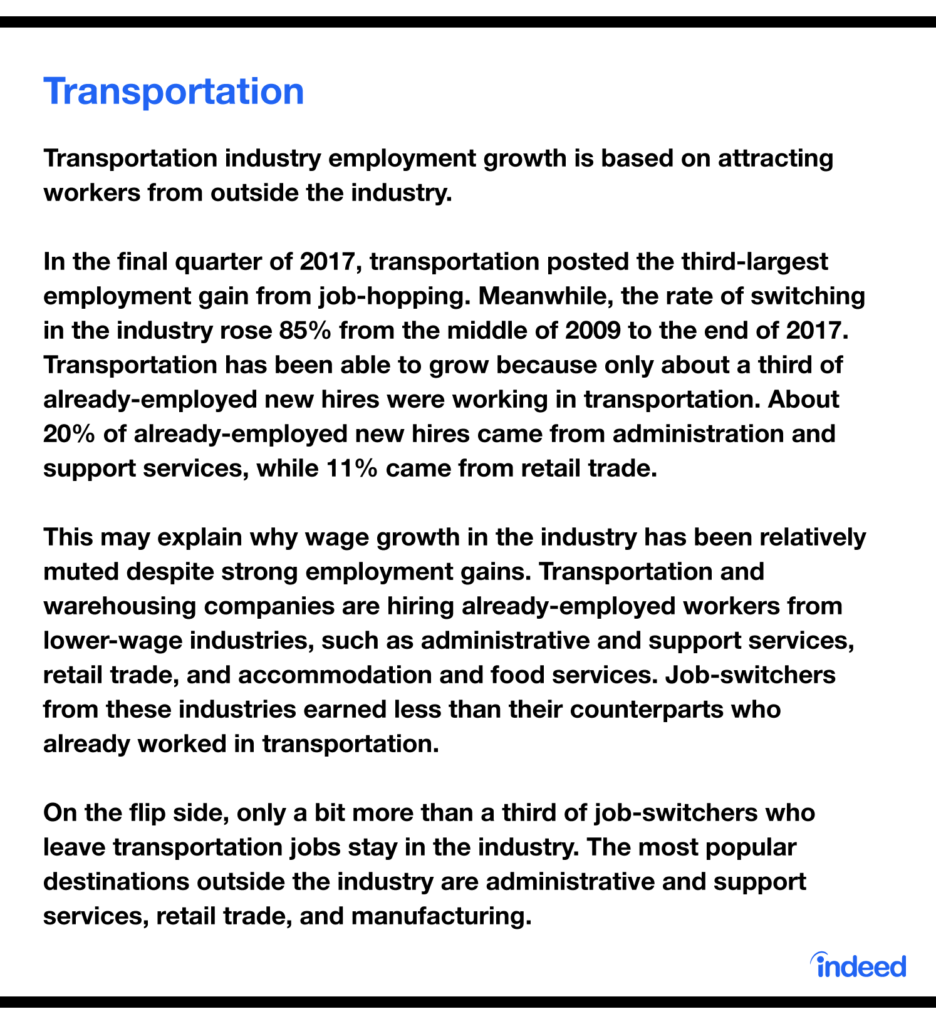

Workers usually leave industries when they switch jobs

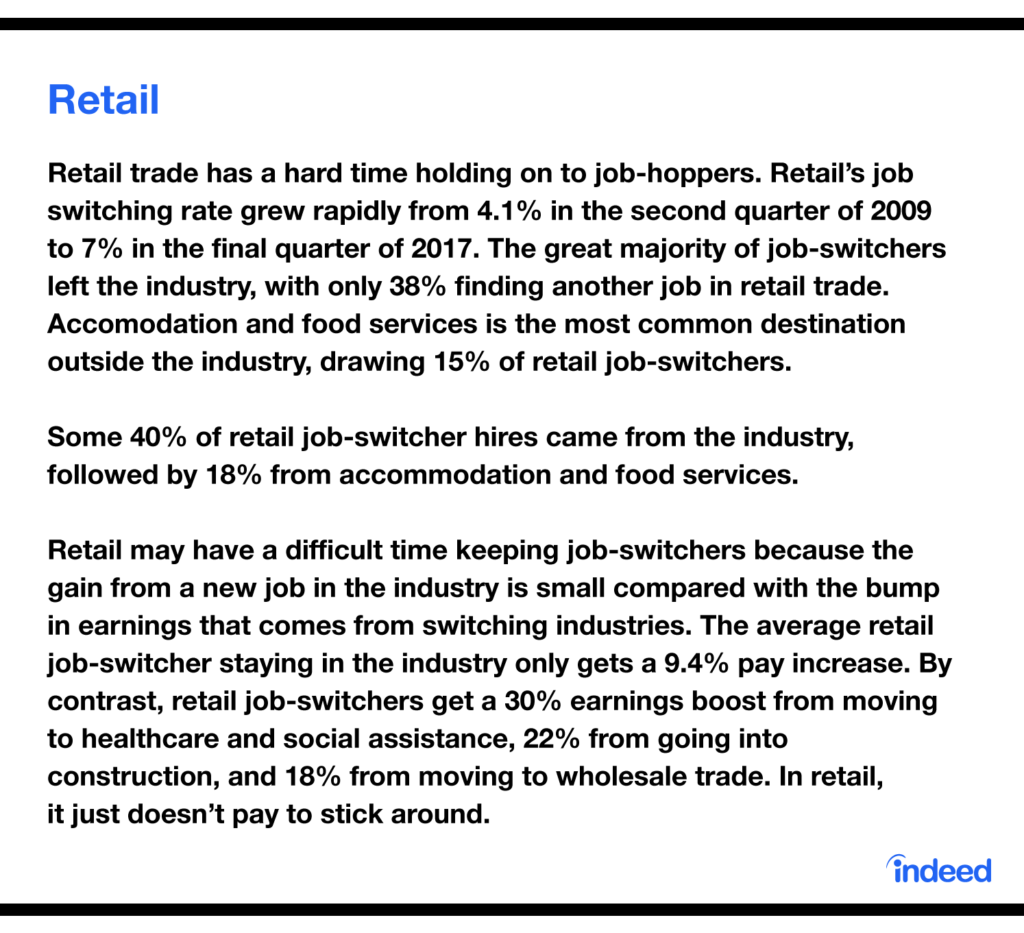

When workers switch jobs, they typically also change industries. In fact, the only two industry groups that most job-switchers stay in when they take new jobs are education and health services, and construction.

The reason why workers jump industries so often is plain — lots of occupations are found across a wide range of industries. For example, all kinds of enterprises need accountants. So if an accountant at a retail company gets a new position at a hospital, that person is not only switching jobs, but industries as well.

This also explains why such a high percentage of job-switchers in education and health services stay in that industry group. Nurses overwhelmingly work in healthcare and teachers overwhelmingly in education. Their experience and skills are highly specialized and aren’t easily transferred to other industries.

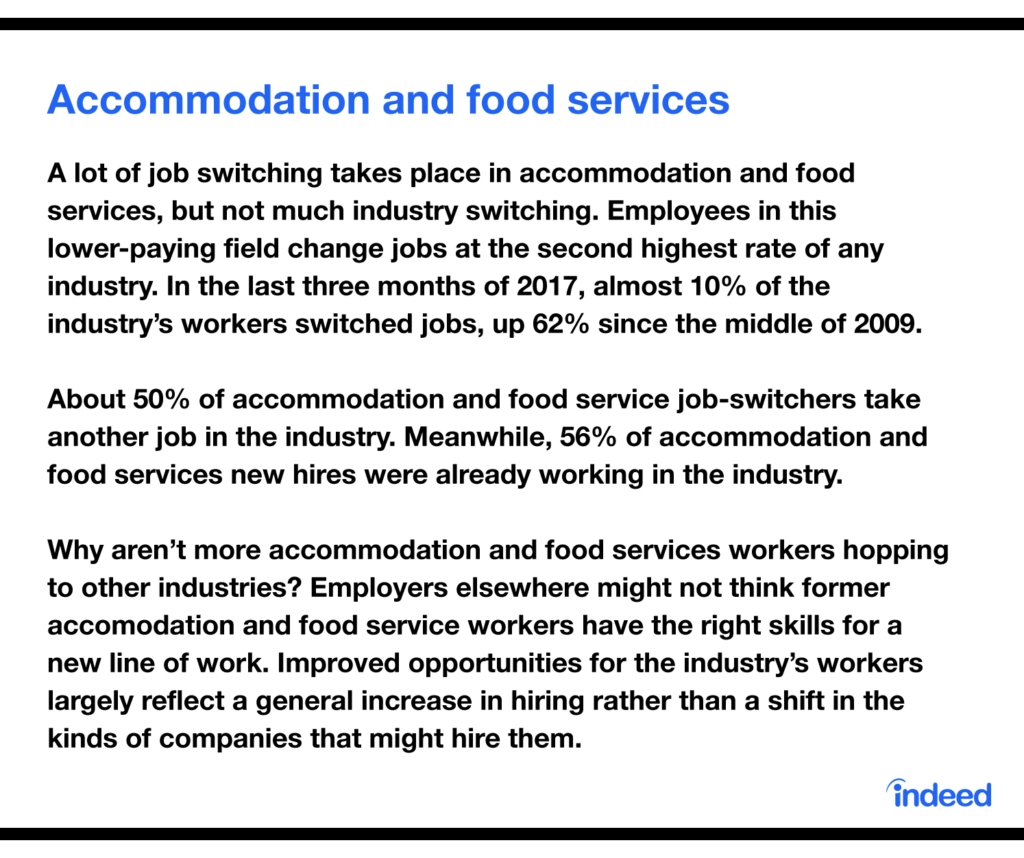

Although most job switching also involves industry switching, the rate that workers move to different industries when they switch jobs hasn’t changed much. Consider workers in accommodation and food services. These workers have better chances of changing jobs in a tight labor market, but the likelihood they will move to different industries when they switch jobs is about the same as it was 10 years ago. The bottom line: In a stronger labor market, more workers get new jobs in new industries. But that’s due to a higher overall rate of job switching, not because job-switchers are more likely to venture into new fields.

How job switching affects employment in different industries

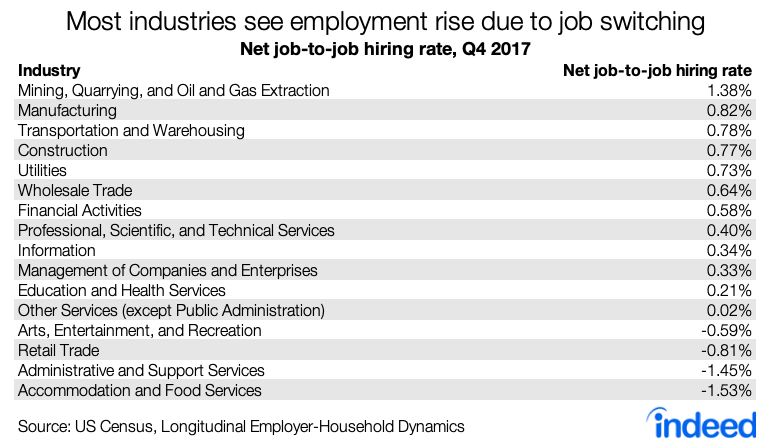

Job switching isn’t a net negative in most industries. In fact, industries usually post gains in total employment because of job switching.

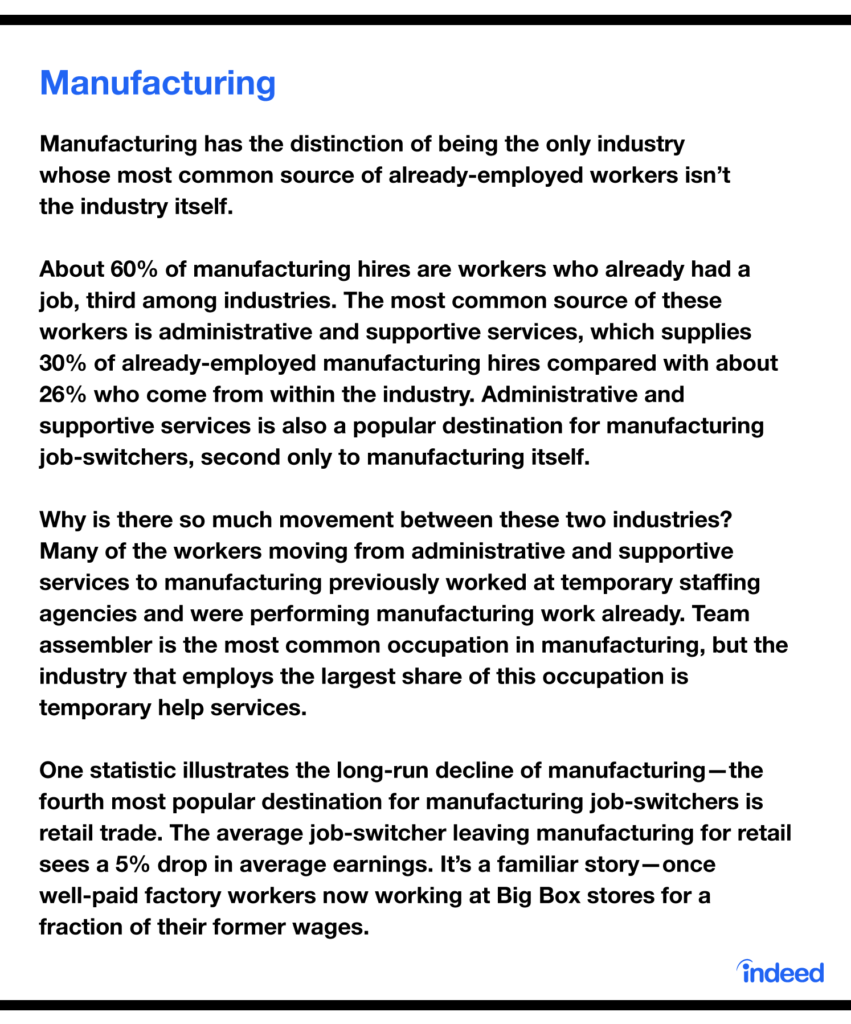

For example, manufacturing employment grew during the last three months of 2017 from job switching. While 3.5% of manufacturing workers left jobs, that was more than offset by job-hoppers who took manufacturing positions. These new manufacturing workers boosted industry job rolls 4.3%. Counting employed manufacturing workers who left the industry and those who came into the industry produces a net job-to-job hiring rate equal to 0.82% of total manufacturing employment. So while there was a lot of churn, manufacturers ended up with more employees thanks to job switching.

Of course, not all industries see net employment gains from job switching. In a few, mostly low-wage, industries, job switching subtracts workers. For example, in accommodation and food services, an exodus of job-switchers for other industries shrank employment 1.5% in the last quarter of 2017. Employment increased 8.4% from hiring workers who already had jobs, but 10% of accommodation and food services workers left their jobs for new ones.

What job switching means for employers

From an employer’s point of view, job switching can present problems. When workers change jobs, employers have to hire and train replacements. And that’s not easy when the job market is strong. A booming economy reduces the ranks of the unemployed, most of whom probably had jobs recently and can easily find work. As the pool of unemployed job seekers shrinks, employers must turn to new sources.

So who benefits?

- First, employers shift their hiring away from the jobless and toward those who are already employed. This happens in every industry, although some industries still mostly hire workers who have been out of work for some time.

- Second, employers are more apt to hire workers with lower levels of education. The share of new hires with less than a college degree is increasing as the labor market strengthens.

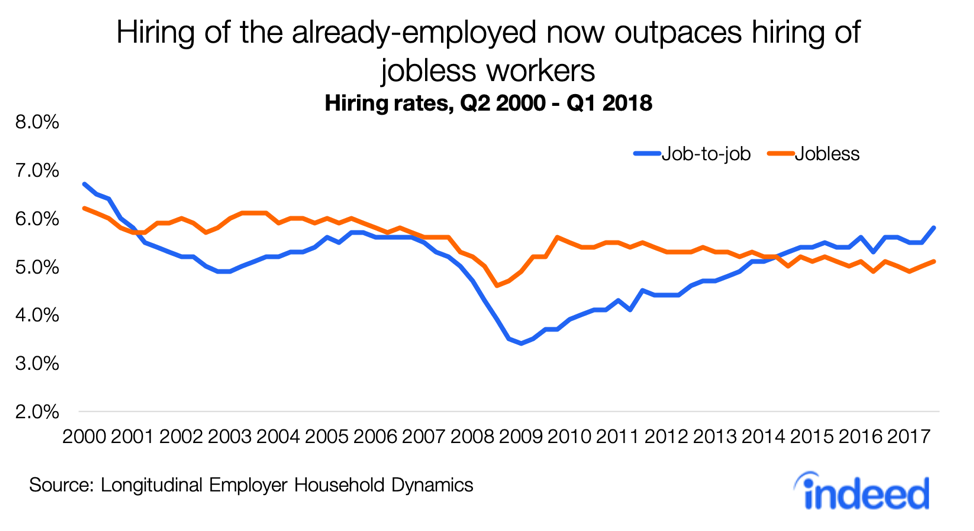

Employers have shifted hiring toward job seekers who are already working

In a job market recovery, timing varies for hiring different kinds of workers. Employers first turn to the ranks of the jobless. After a while, the number of unemployed workers falls so much that employers must look elsewhere. At that point, the hiring rate of already-employed workers starts to climb. Eventually, employers mostly hire people who have jobs.

This is good news for employed job seekers. Increased hiring competition is a boon for those who are looking for higher pay, better benefits, more favorable working hours, or other improvements in their work situations.

The shift toward hiring already-employed job seekers is stark and has taken place in every industry. During the Great Recession, in the second quarter of 2009, only 38% of new hires were job-switchers compared with 50% in the last quarter of 2017.

An employer is probably hiring a job-switcher from another industry. Only three industries groups — accommodation and food services, education and health services, and construction — get more than half their job-switchers from other employers in the same industry.

High-wage industries hire already-employed workers

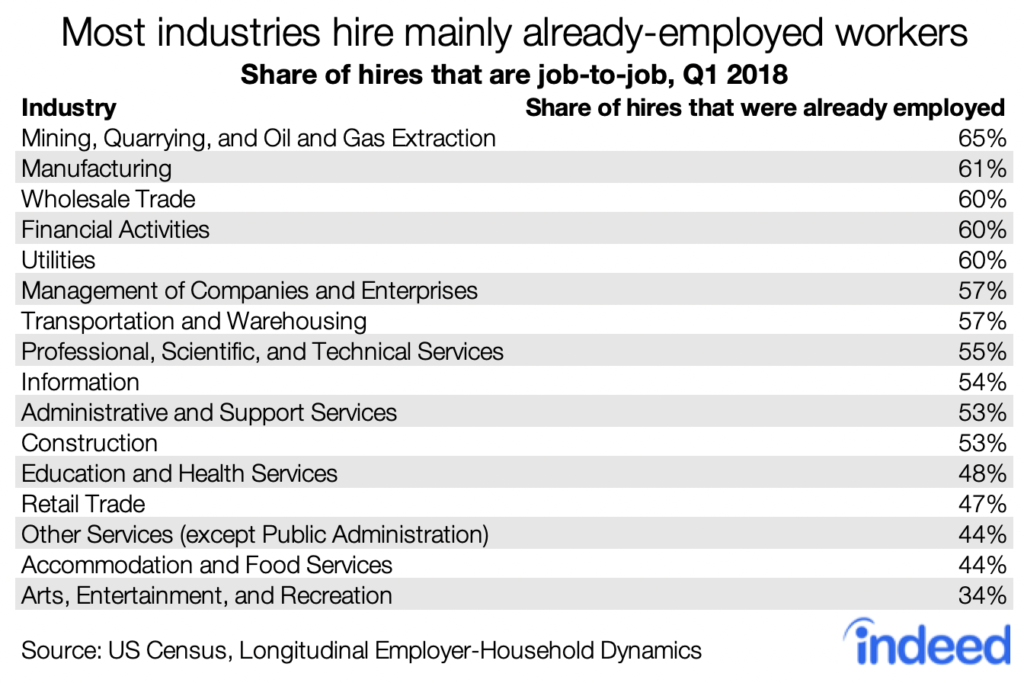

The tendency of employers to hire already-working job seekers varies by industry. In the first quarter of 2018, 65% of new hires in mining were job-switchers, but the share in arts, entertainment, and recreation was only 34%.

In general, higher-paying industries, such as finance and insurance, tend to take more job-switchers. This trend doesn’t necessarily reflect education levels. Manufacturing has the second-highest share of already-employed new hires. The association of job switching and higher pay suggests employers in those industries are more likely to stress recent work experience when making hiring decisions than their counterparts in lower-paying industries.

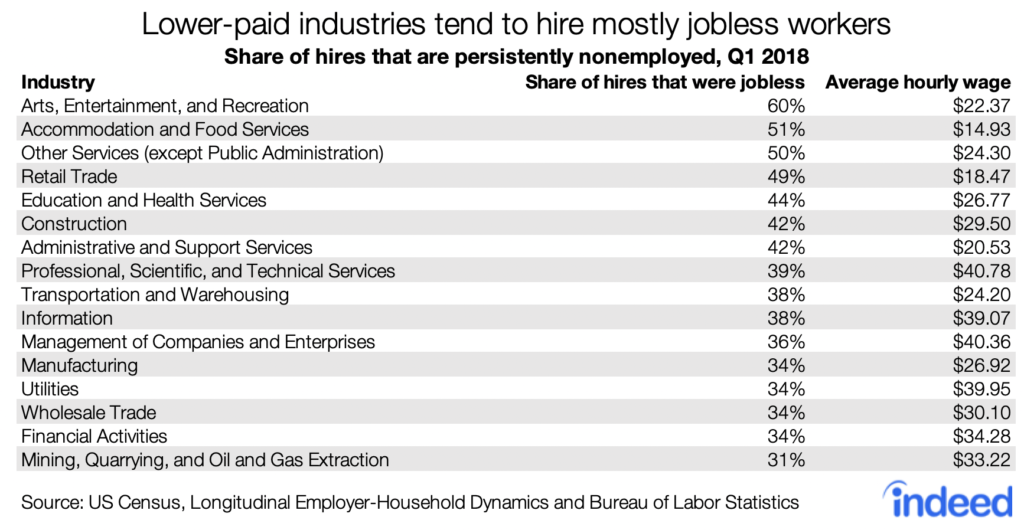

Low-wage industries hire the jobless

In today’s job market, even people who have been out of work for a while are in demand. In three industries, more than 50% of hires were job seekers who had been out of work for at least three months. The industries that hire these longer-term jobless workers, such as accommodation and food services, tend to pay lower wages. In short, those who’ve been out of work for a while can find jobs, but the positions they take might not pay much.

The same holds true for less-educated workers. In the first quarter of 2018, people without a college degree represented a higher share of all hires than at the beginning of 2009. To be sure, roughly 60% of people in the workforce lack a college degree. As the labor market tightens, hiring tilts further toward these less-educated workers. Employers are more willing to hire such workers even though they might not be exact fits for the jobs they are taking.

Conclusion

A stronger job market is presenting real opportunities for workers who are already collecting paychecks. It is a terrific time to look for a new job or bargain with a current employer for higher compensation.

At the same time, the hiring boom is forcing employers to adjust recruitment strategies. They may have to offer more generous pay and benefits, as well as hire job seekers who lack credentials previously considered essential, such as a college degree or industry experience. It might just turn out though that these workers are capable and quick to learn, and excellent additions to the workforce.

Methodology

The main data source for this report is the Job-to-Job Flows (J2J) data from the US Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics program. This is constructed using administrative data that allow researchers to see matches between workers and employers as well as when those matches begin (a hire) and when they end (a separation). The data on moves between industries and resulting wage changes are from the origin-destination dataset and were aggregated nationwide using state-level data. The data cover up to the first quarter of 2018. Data from Wyoming, Alaska, Maine, and New Hampshire are not available for the full-time frame, so data from the first quarter of 2016 aren’t perfectly representative.

Job switching is defined as a worker moving from one job to another within the same or the adjacent quarter.

A jobless hire is defined as a hire of a worker who has no registered earnings from a job for a full quarter.

Earnings growth is defined as the quarterly growth rate of average quarterly earnings for workers who directly switched jobs in one quarter.