Key points

- The Canadian labour market has fared well in 2019, posting strong job growth throughout most of the year before slipping in the fourth quarter.

- Conditions have remained favourable for job seekers, with the working-age employment rate hitting a new high in September, though weakness continued in Prairie provinces.

- A tighter labour market has kept the job vacancy rate elevated, while wage growth picked up by varying degrees depending on the measure.

- The outlook for 2020 is cloudy, partly due to uncertainty about whether the broader economy will be strong enough to keep job growth at a solid pace.

Looking at the Canadian labour market in 2019, it’s hard to miss the similarities between this and last year. An already elevated share of Canadians age 15 to 64 with jobs hit a new high before falling back toward the end of the year, while employers continued to report hiring difficulties. Certain indicators like jobless spells made encouraging strides and wage growth showed signs of life. At the same time, many areas of weakness persisted, particularly in the Prairies and the natural resource sector. Looking to the year ahead, the sources of concern haven’t changed, mainly relating to the job market’s durability in the face of subdued domestic economic growth and an uncertain global environment.

Another job seeker’s labour market in 2019

Canada has added a lot of jobs in 2019. The year-over-year rate of employment growth outpaced population growth, which itself hit a multi-decade high, for nearly the entire year. It took a sharp tumble in November for employment and population growth to converge again.

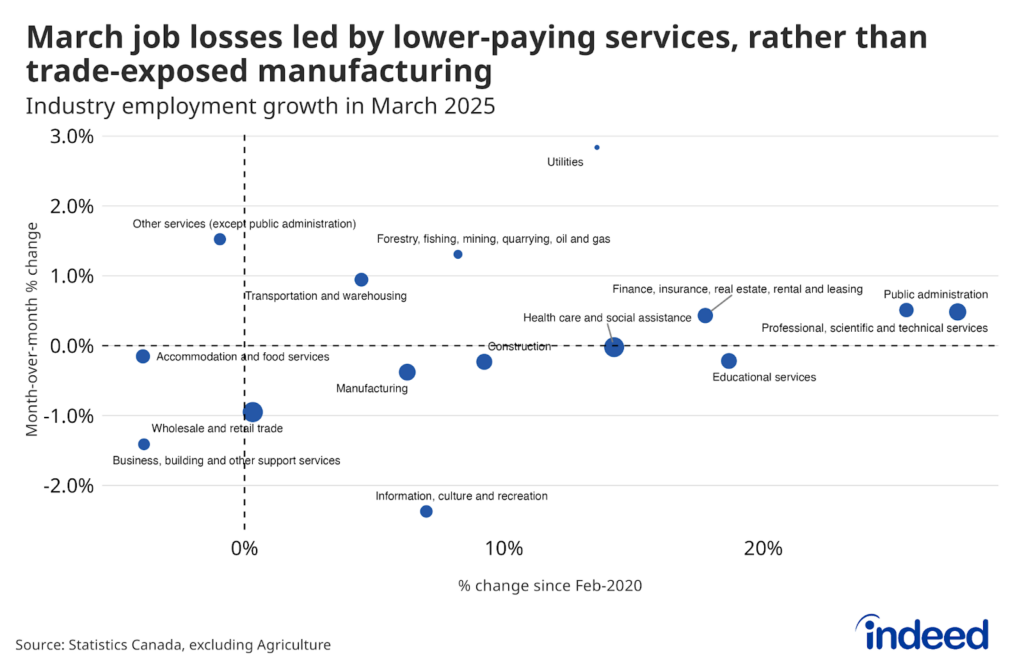

The service sector has driven these gains, with predominantly public sector-related industries like healthcare, education, and public administration posting strong growth. Jobs in professional, scientific, and technical services, which includes much of the Canadian tech sector, have also expanded rapidly, continuing their strong pace over the past few years. Transportation and warehousing, another of Canada’s fastest-growing sectors in recent years, has also added jobs, but at a slower rate than in 2018.

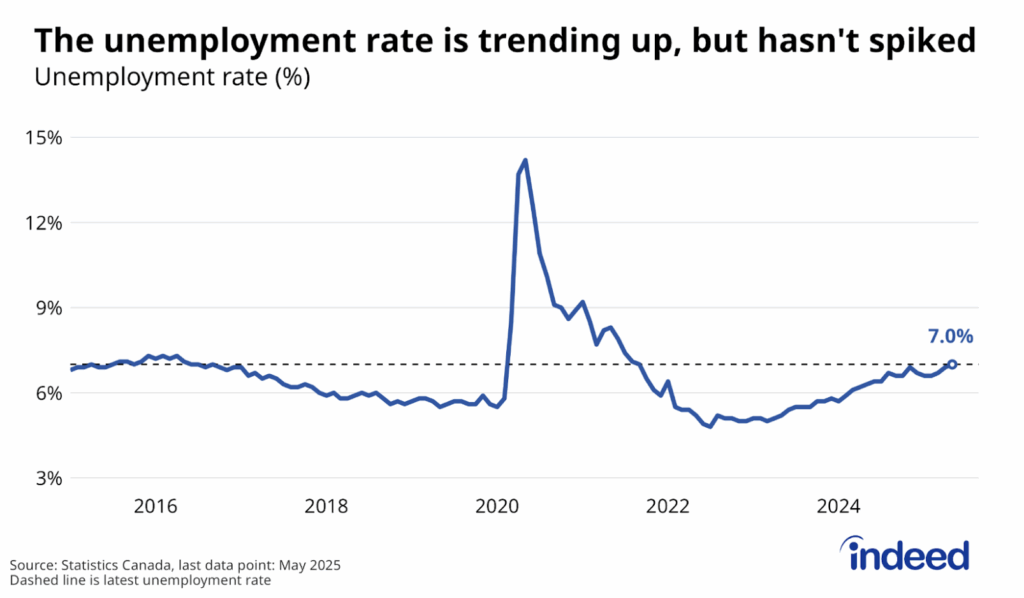

Swift overall employment growth sent the working-age employment rate — the share of Canadians age 15 to 64 with a job — to a record 74.7% in September. A weak start to the fourth quarter knocked the rate back to 74.2% in November, where it began the year, but it remained 1.7 percentage points higher than in early 2016, showing a similar pattern as the overall unemployment rate. Other positive developments for job seekers have included declines in underemployment, that is, those working part-time who’d rather full-time work, as well as shorter lengths of jobless spells.

Improving conditions for job seekers have made for a tougher hiring environment. Both the Bank of Canada’s Business Outlook Survey and the Business Barometer Index of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business find a relatively high share of employers reporting their operations are straining because of difficulties finding workers. In both cases, reports of shortages have generally grown in tandem with the declining unemployment rate. This suggests that tougher hiring conditions primarily reflect broad labour market tightening rather than rising mismatch between job seeker skills and job openings.

Employer competition for fewer unemployed candidates has boosted job vacancies. The job vacancy rate hit 3.5% in the second quarter, according to Statistics Canada’s Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, a full percentage point higher than in mid-2016. Still, the pace of growth slowed this year following large increases over the previous two years, suggesting the vacancy rate could be set to plateau.

The tightening job market could also be translating into stronger wage growth. After softening in the second half of 2018, year-over-year hourly earnings growth picked up to 2.6% in the second quarter of 2019, according to the Bank of Canada’s Wage-Common measure, which reflects trends across several wage indicators. Preliminary data according to the Bank’s October Monetary Policy Report suggests a further acceleration to 3% in the third quarter. While not quite at the perhaps exaggerated rate above 4% pace reported in recent LFS data, the projected third quarter wage-common growth rate still represents progress.

Prairie job markets continue to struggle

The improvement Canada’s job market has displayed in recent years isn’t evident in all regions. Conditions have strengthened most in Quebec and B.C., while Ontario has registered more gradual gains. Working-age employment rates in Atlantic Canada have also ticked up, although they remain lower than elsewhere. However, the Prairies have missed out on any improvement. The employment rate in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba together is down 2.1 percentage points from the start of 2015, easing further over the past year.

Working-age residents of the Prairies are employed at higher rates than most other provinces, even though unemployment rates — especially in Alberta — are relatively high. That’s because a greater share of the population is in the labour force. Still, Prairie labour markets aren’t operating like they were before the oil price crash. Weekly earnings growth in Alberta has lagged the rest of Canada, while the lengths of typical jobless spells in oil-producing provinces have generally gone from the among the shortest to some of the longest in the country.

Questions for the year ahead

The Canadian labour market has had a solid 2019, notwithstanding the ongoing weakness in the Prairies. However, heading into 2020, we’re left with more questions than answers on whether progress can continue, especially in light of a rough start to the fourth quarter.

1. Have we hit full-employment?

With the unemployment rate low and some wage growth indicators picking up, we could be approaching a point where increased difficulty finding workers puts a lid on the pace of further job gains. This might play out differently by region. For instance, Quebec and B.C. are potentially closer to this point than other provinces because their working-age employment rates are well above their peaks last decade. Meanwhile, there’s certainly room for improvement in provinces like Alberta, but employers there currently have limited appetite to hire. As a result, the national labour market performance could come down to whether Ontario employment rates can catch up to Quebec and B.C.

2. Is the economy strong enough to keep job growth chugging?

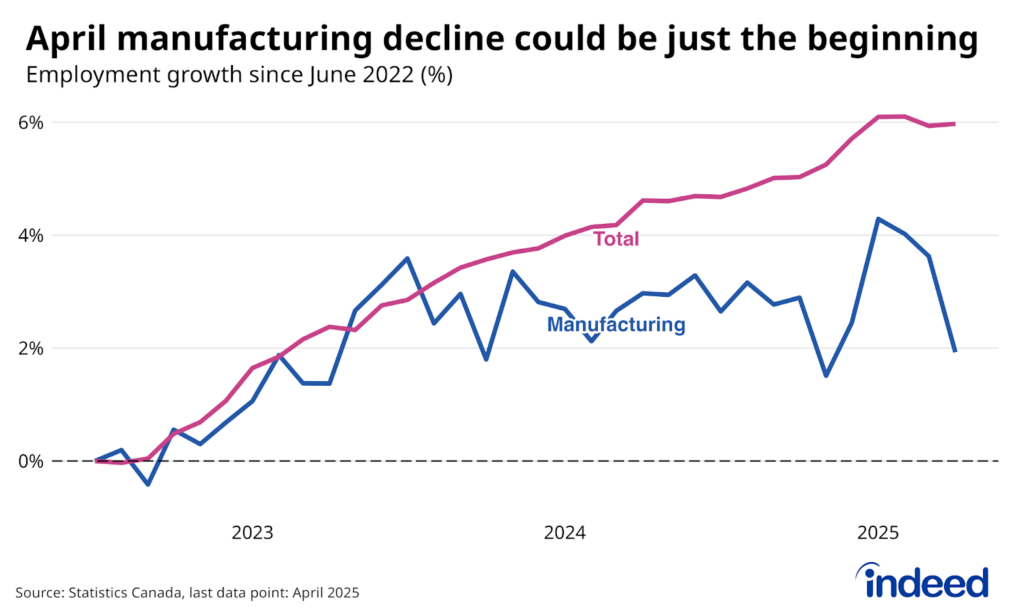

Even if there’s capacity for further labour market improvement, will the broader economy cooperate? Throughout most of 2019, job growth has fared better than other measures of economic activity, like GDP growth. One factor helping explain the divergence between the growth of the economy and growth of employment has been that Canadians have averaged fewer hours at work per week than they did in 2018. However, if projections of subdued growth are on target, employer demand for workers might cool, which could slow job gains. We could be seeing signs of this already, especially in goods-producing industries like manufacturing and natural resources, where employment is down in recent months.

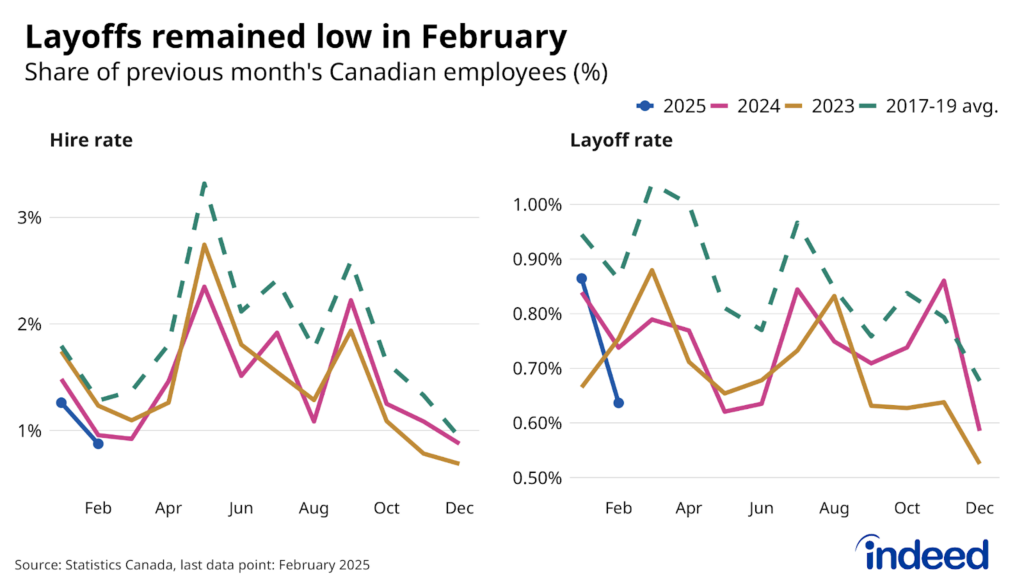

To be sure, a slowdown in job growth wouldn’t spell doom for the Canadian labour market, given its solid progress over the past few years. It would take an outright recession to substantially reverse these gains. In this case, we should be watching for a sharp jump in newly unemployed workers for signs of an economic downturn.

3. If wages keep rising, how will employers respond?

Recent strength in wage gains has occurred despite weak productivity growth and stable inflation. Should these trends continue in 2020, rising labour costs will probably come at the expense of business profits. With productivity growth stuck in neutral, achieving meaningful real wage growth for Canadian workers depends on them getting a bigger share of the pie. However, if this is the case, how long will it be before employers adjust and how will they do so?

A rosy scenario would be for businesses to respond to a higher wage environment by making productivity-enhancing investments, helping boost both profits and wages. However some employers might scale back hiring, which could dampen further wage gains. Others might try to pass on higher labour costs to customers, potentially putting upward pressure on inflation.

Overall, the Canadian labour market made further strides in 2019, at least before its fourth-quarter dip, building off the progress seen in recent years. This has made for a job seekers market, while an elevated share of employers are finding it tough to bring on workers. At the same time, weakness in the Prairies and an uncertain outlook cloud the picture, reflecting persistent economic challenges at home and potential deterioration abroad.

Methodology

Data in this post reflects Labour Force Survey data through November 2019, Survey of Employment, Payrolls, and Hours data through September 2019, and Job Vacancy and Wage Survey data through the second quarter of 2019.