Key points

- The Canadian employment situation has improved since the end of 2015, but progress in unemployment and full-time employment rates has varied across the electoral map.

- Areas where the NDP was competitive in 2015, usually splitting with the Liberals, saw major improvement, primarily in Quebec and B.C. Gains were more modest in places the Liberals swept or split with the Conservatives, while solid Conservative regions lagged.

- Voter perception of the labour market won’t be uniform across Canada. Confidence in the job outlook might be higher in regions where the NDP and Bloc Quebecois had some success last election, and less optimistic in a number of areas where the Liberals and Conservatives will likely be competing.

Recent job gains have been uneven across regions

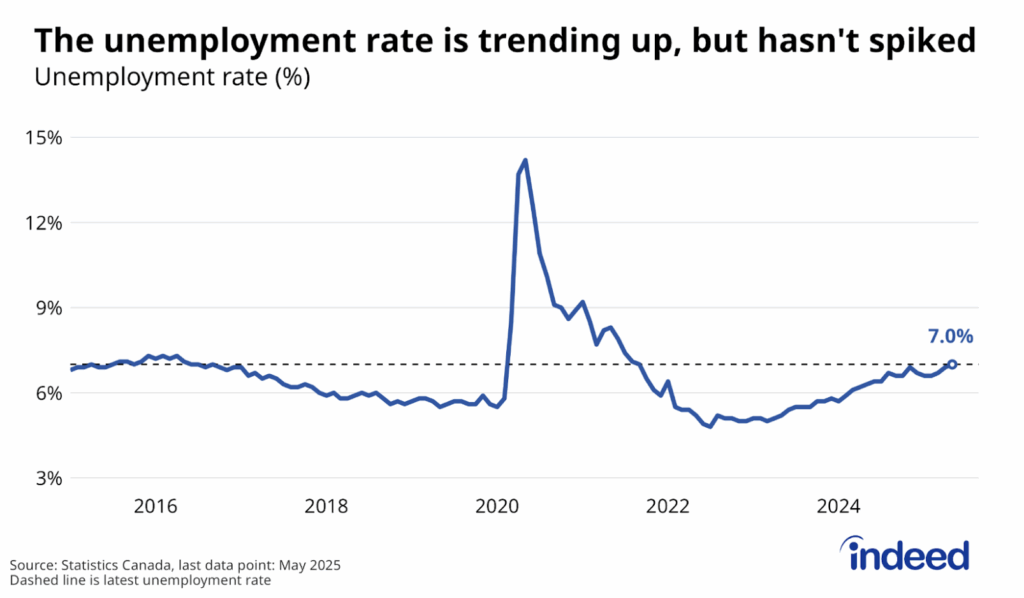

The Canadian job market is generally on a stronger footing heading into this year’s election than it was in 2015. Not only has the nationwide unemployment rate fallen to near multi-decade lows, but the working-age employment rate — the share of Canadians age 15-64 with a job — just hit a new all-time high. With jobs and the economy once again a key voter concern, will these trends have a significant impact at the ballot box?

It might vary across the country. We find that recent labour market strength has been concentrated in certain areas of the 2015 electoral map. In particular, regions where the NDP or Bloc Quebecois were competitive, typically splitting with the Liberals, have seen substantial improvement, mostly in Quebec or B.C. Meanwhile, there’s been more modest progress in areas the Liberals either swept or split with the Conservatives, primarily in Ontario and Atlantic Canada. Finally, the post oil-crash labour market malaise in Alberta and Saskatchewan has had solid Conservative regions lagging.

These uneven regional employment trends could affect the election. With the Liberals the incumbent party defending seats in every province, their popularity might vary across the country depending on how each area’s job market has done. This would imply a potential edge in Quebec and B.C., where the NDP and Bloc had some success in 2015, and less of an advantage elsewhere.

At the same time, with labour markets showing at least some improvement in most parts of the country, voters might be focusing less on the job outlook per se and shifting their attention to other issues, including the cost of living — itself related to the pace of wage growth — and the environment. The matchup is shaping up to be a close one. How voting patterns do or don’t shift in different regions will help give an indication of the job market’s role in the 2019 election.

Tracking employment growth based on 2015 election results

Tracking recent job market developments across the Canadian political landscape can be a challenge. Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey provides up-to-date employment data for 34 select metropolitan areas (taking Ottawa and Gatineau separately), all of which contain multiple electoral districts. Unfortunately, the jobs data aren’t detailed enough to assess trends at the riding level.

To get around this, we categorize metro and the remaining non-metro areas of each province based on the results of the ridings located within their boundaries in the last election (see methodology). Areas where one party took at least three-quarters of electoral districts, like Toronto (89% Liberal), and Calgary (82% Conservative), are classified by their top party. Other regions are categorized according to their top two seat-winners. For example, Vancouver is classified as Liberal-NDP (63% Liberal, 25% NDP), while non-metro Ontario is classified as Liberal-Conservative (63% Conservative, 25% Liberal). Given their similarities, we analyze regions that split between the Liberals and NDP or Bloc as one group. Consistent with their parliamentary majority, most Canadians live in regions where the Liberals won seats last election.

Job market improvement concentrated in regions where the NDP was competitive

The job market pick-up since the end of 2015 in NDP and Bloc-competitive areas like Vancouver and Montreal is evident according to several measures. In August, the average unemployment rate over the previous 12 months in Liberal-NDP/Bloc regions was 2.1 percentage points lower than in December 2015, while other NDP-competitive areas also saw a substantial decline. Regions the Liberals swept or split with the Conservatives also made progress, but with declines closer to 1 percentage point. Unemployment was up slightly in Conservative areas.

The same pattern is evident when looking at the share of Canadians between 25 and 54 — prime working age — with full-time jobs. This measure is a complement to the unemployment rate because it isn’t influenced by people leaving the labour force or changes in part-time work.

Full-time employment rates in Liberal-NDP/Bloc regions have jumped 3.4 percentage points since the end of 2015 to a record level, while rates in Liberal and Liberal-Conservative areas were up a less striking 1.3 and 1.4 percentage points respectively. Prime-age full-time employment rates in Conservative regions only edged up slightly, but remain highest in Canada, reflecting higher shares of the population in the labour force.

Most areas in each political bloc followed their group’s overall trend, but some stood out with unique patterns. Despite being classified as Liberal or Liberal-Conservative, prime-age full-time employment rates in areas like Ottawa, Sudbury, and non-metro Ontario improved substantially, while they lagged in others, like London, St. Catharines-Niagara, and Winnipeg. Quebec City bucked the trend of Conservative regions in the Prairies, posting solid gains like the rest of its province.

Job growth was more broad-based where the Liberals split with the NDP or Bloc

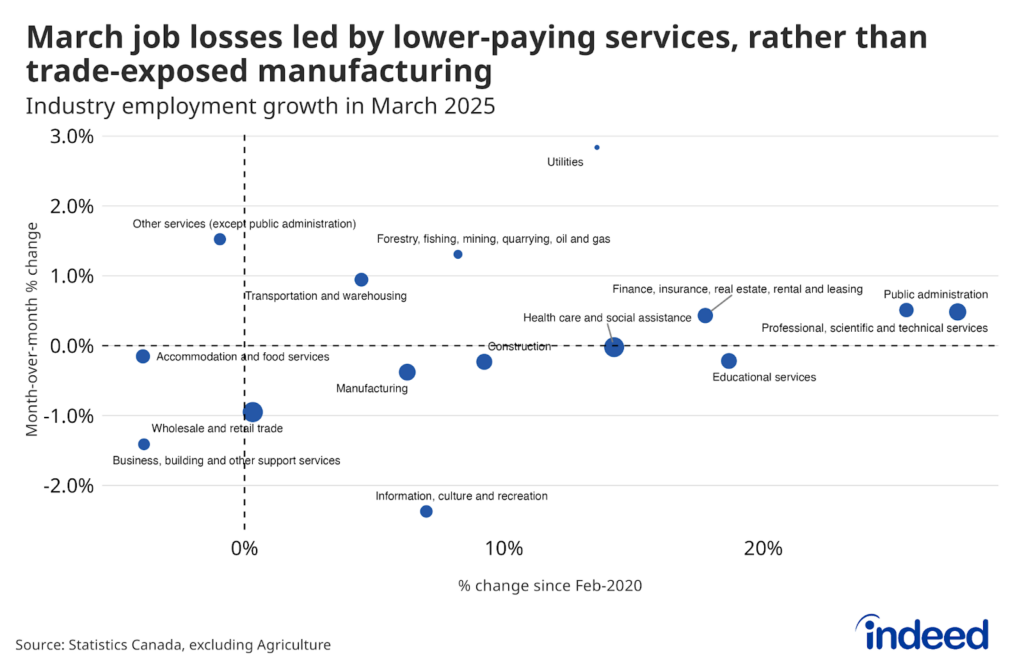

What kind of jobs are on the rise in Canada? In a trend predating the last election, Canadian employment growth has been led by typically mid- and well-paying white-collar occupations. Meanwhile, the number of people working in lower-paying jobs, often involving manual labour and office support, has lagged. This pattern has been evident across the country, with employment rates in lower-wage jobs falling relative to other occupations in all regions between 2015 and 2018. (We exclude NDP & Other regions because of smaller sample size.)

At the same time, growth in mid- and high-paying roles was more varied. High-paying roles led job growth in Liberal regions, especially in Toronto, while gains in Liberal-Conservative and Conservative regions tilted toward mid-wage roles.

Job growth was more broad-based in areas the Liberals split with the NDP and Bloc. In particular, while employment rates in higher-paying roles rose similarly as in Liberal and Conservative areas, employment in mid-wage occupations surged, outgaining the rest of Canada. Meanwhile, the drop in lower-wage jobs was less severe than in Liberal or Conservative regions.

In Liberal-NDP/Bloc regions, all three wage tiers were represented among occupation groups adding the most jobs. These included mid-paying administrative roles, high-wage professional roles in business and finance, and lower-paying service representative positions. All three occupations probably contributed to growth in the finance, insurance, and real estate sector, which added more jobs in these regions than elsewhere.

Overall, this suggests that labour market gains in areas the Liberals split with the NDP or Bloc have been greater than elsewhere in part because job opportunities have been more broad-based, especially for individuals with less education. Consistent with this, employment rates among adults of prime working age without post-secondary education have shown more improvement in B.C. and Quebec since the end of 2015 than in Ontario or Alberta.

Voters probably feeling better about the job market in some regions than others

Recent labour market developments are just one of many factors that could influence the 2019 election. Nonetheless, analyzing after the polls close how seats shift in different regions could give a sense of the job market’s impact. B.C. and Quebec have seen the most improvement since the last election. One sign to watch to see whether employment growth played a role would be if the Liberals end up faring better in these areas than elsewhere. Voters in other parts of the country may be less upbeat about the current labour market situation.

Methodology

We track how the job market has evolved across the Canadian electoral map by grouping together metro and non-metro areas based on the 2015 electoral results of the ridings located within their borders, determined using Statistics Canada’s boundary files. Judgment was used in cases where ridings crossed metro boundaries. We focus on metro and non-metro areas rather than economic regions because Statistics Canada publishes the Labour Force Survey (LFS) in greater demographic detail at the metro level.

Areas where the top seat-winning party took at least three-quarters of electoral districts are classified by their top party. Other regions are categorized according to their top two seat-winners. Given their relatively small population size, we analyze solid NDP regions together with areas the NDP split seats with the Greens, Bloc Quebecois, or Conservatives. The classification of all metro and non-metro areas is listed below.

**Since the second and third-winningest parties in Regina and Sherbrooke each took home an equal number of seats, we used the total vote count of each party in both metros to break the tie.

We then group together population and employment data from the LFS by each political grouping to calculate unemployment rates and full-time prime-age (25-54) employment-to-population ratios for each region. Results presented reflect 12-month moving averages of the three-month non-seasonally adjusted averages published by Statistics Canada, through August 2019.

To analyze job growth by occupational wage tier in each region, we grouped Canadian occupations at the two-digit NOC level into low-, mid-, and high-paying jobs based on their national 2018 average hourly wages using a quantile process. We present changes in employment-to-population ratios by wage tiers rather than raw employment growth to avoid conflating the effect of population growth on job growth.