Key points:

- There are patterns to which people, sectors, and places tend to fare worse or survive better in recessions. People who are disadvantaged in the labor market to begin with tend to do even worse in recessions.

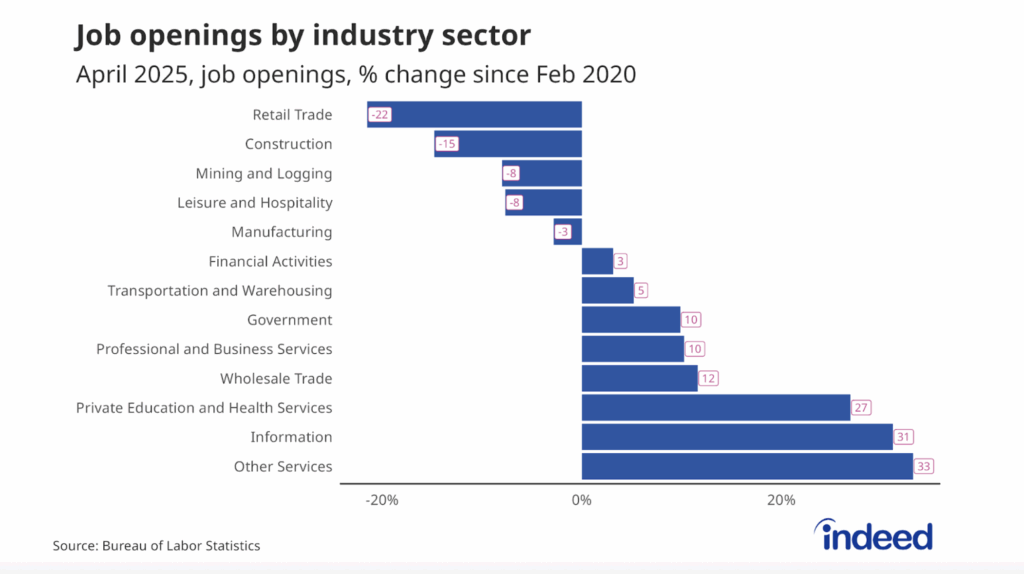

- The most resilient industry sectors are services provided locally that people need even in bad times, such as health care, education, and local government, plus food manufacturing and food stores.

- For recruiters, some of the challenges of today’s tight labor market might get easier in a recession. Organizations still hiring in a downturn should find many strong candidates.

- For job seekers there’s no silver lining: In downturns, there are fewer available jobs—and more job seekers competing for each one.

With unemployment at a near-50-year low, it’s hard to believe that recession fears are rising—but they are. In recent months, articles like “Companies Need to Prepare for the Next Downturn” and “You Never Know When a Recession Will Sneak Up on You” have appeared. Economic forecasters surveyed by the Wall Street Journal in May thought there was a 23% chance of a recession in the next 12 months, up from 15% a year ago. That means recession is unlikely in the next year—but worries persist even so.

Why have recession fears increased? It’s not because of bad labor market news. Today unemployment is lower, wage growth is higher, and job growth is just about as strong as a year ago. But the economy faces real risks. Here’s what those are—and what this means for employers and job seekers.

Four risks facing the economy

First is that today’s growth is unlikely to last forever. Unemployment at 3.6% is more than half a point below where the Federal Reserve thinks it will settle eventually, and job growth is much faster than what’s needed to keep up with the growth of the working-age population.

Second are political risks to growth, like a trade war with other countries or reduced immigration. Third, global shocks—like Brexit—could reverberate far beyond the borders of Europe and impact the U.S. also.

And fourth, long-term drags on growth like an aging population and slowing productivity mean that the good times aren’t as good as they used to be.

What will the next downturn look like?

When the next downturn comes, what might it look like? The past offers lessons. The five times unemployment peaked in the past 50 years—2009, 2003, 1992, 1982, and 1975—paint a mixed picture. Each slump was different. However, even though economists still debate the causes of these recessions, there’s some agreement about what triggered each.

Sub-prime mortgages and a broader financial crisis were the story in 2009, with Sunbelt metros like Las Vegas and Phoenix, as well as Detroit, hardest hit.

But 2003 was a dot-com bust, centered in expensive coastal metros of San Jose, Boston, and San Francisco. 1992 was different still, with the savings and loan crisis and defense cutbacks—and southern California had the biggest job losses.

The 1982 downturn was brought on by the energy crisis and high interest rates, and the Rust Belt fared worst—and nationally unemployment rose even higher than during the Great Recession in 2009.

And the 1975 slump, aggravated by an oil shock and price controls, was worst in Detroit, Charlotte, and Miami.

How people, places and industries fare in recessions

The past 50 years might look like a game of recession roulette, with different industry sectors and places at the heart of each downturn. But, in fact, there are patterns to which people, sectors, and places tend to fare worse or survive better in recessions.

People who are disadvantaged in the labor market to begin with tend to do even worse in recessions. The less educated and racial and ethnic minorities see bigger increases in unemployment during recessions than other groups. This is the flip side of the current boom, which has brought larger wage gains and bigger drops in unemployment to most groups of people who are usually left behind. In short, gaps tend to narrow in booms and widen in recessions.

Among sectors, goods-related industries tend to be more volatile than service industries. Goods-related industries like energy, mining, construction, and manufacturing are affected by oil prices and shifts in global demand. The most resilient sectors—those whose worst years were less bad than other sectors—are services provided locally that people need even in bad times. In recent decades, health care, education, and local government employment have been most resilient, along with food manufacturing and food stores. After all, when bad times come, it’s easier to cut back on vacations and gadgets than on food and medical expenses.

The most resilient places are those where the most resilient sectors are concentrated. Looking at each metro’s worst year of job growth since 1969, Austin held up best—in no year did employment ever fall by more than 1%. San Antonio, Durham NC, and Omaha had only slightly worse worst-years than Austin.

However, not all resilient markets are boomtowns. Rochester NY, Albany NY, and Allentown PA tend to grow slowly, but they neither boom nor bust. Their worst years of the last five decades were better than the worst years of most other metros. The 20 most resilient of the 104 metros with population above 500,000 are shown in the map and have two things in common. Many are college towns, and many are state capitals (plus the national capital).

How should recruiters and job seekers think about downturns?

How should recruiters think about the next downturn, whenever it comes? Like most other industries, the recruiting industry is not immune to recessions. In the Great Recession, employment fell 5% year-over-year at its worst—but hiring was down more than 20% year-over-year.

And yet, for recruiters, some of the challenges of today’s tight labor market might get easier in a recession. Organizations still hiring in a recession should find many strong candidates: at the worst of the Great Recession, there were more than six unemployed workers per job opening—while today there are more job openings than unemployed workers.

Furthermore, fewer workers quit during recessions because fewer other opportunities exist. The quits rate is almost twice as high in today’s tight labor market than it was at the worst of the Great Recession.

For job seekers, though, it’s hard to find the silver lining of recession clouds. In downturns, there are fewer available jobs—and more job seekers competing for each one. The best advice is to take advantage of today’s tight labor market, now that wages are rising and employers are casting their nets more widely to hire.

Go after that dream job today even if it might be a stretch or you’re not the perfect fit on paper—and build up the skills and employment history that will help you through harder times. Finally, both job seekers and recruiters can prepare for the next downturn by looking to hire or to work in more resilient sectors and places.

This post is a condensed version of an Indeed Interactive 2019 keynote speech given by Indeed’s Chief Economist Jed Kolko. It originally appears on the Indeed blog.