Key Points:

- Over the past year, the pace of US workers quitting their jobs picked up, a sign they were more confident they would be able to find new employment.

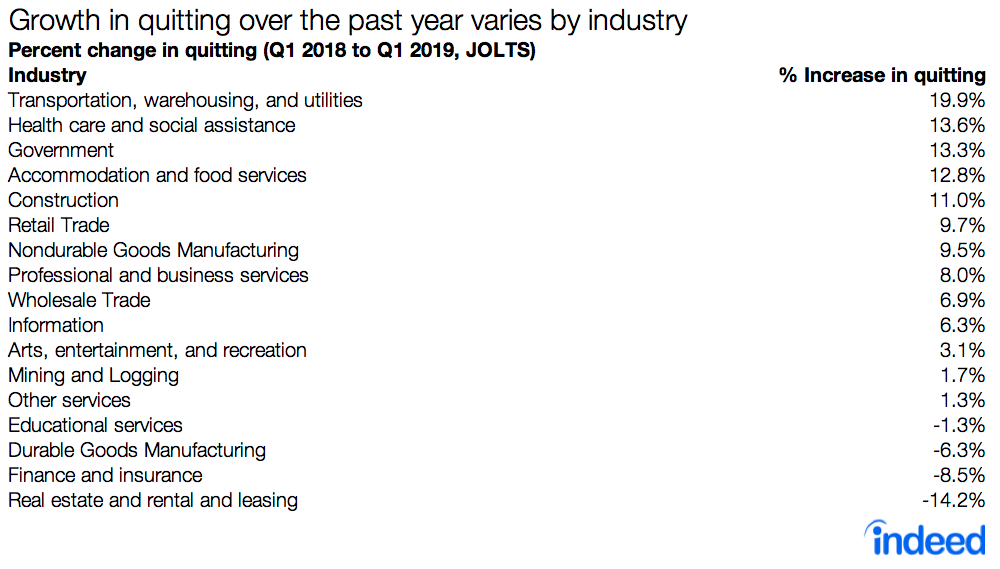

- The pickup was strongest in construction, food service, government, and health care and social assistance. There was also a rapid rise in quits in the transportation, warehousing, and utilities industry, probably due to flat wage growth.

- In a tighter labor market, high wage growth might not be enough to retain talent when pay is rising even more elsewhere.

As the US labor market has gotten stronger, the pace at which workers quit their jobs has started to pick up. More workers voluntarily leaving their jobs is a good economic sign since they probably have new jobs lined up or think they’ll get one soon.

In other words, quitting is an indication that employees and job seekers are more confident. Employers that ignore this trend and fail to adjust pay risk losing valued employees.

Across the entire labor market, quitting rose 8.9% from the first quarter of 2018 to the first quarter of 2019, but the increase varied by industry. The transportation, warehousing, and utilities category posted a noticeable increase, with quits jumping almost 20%. Accommodation and food services, health care and social assistance, and government, all notched quit increases of 13-14%. Construction was just behind, with quits climbing 11%.

Why are more workers quitting?

Quitting can rise in an industry for a number of reasons, but the two main ones are a strong labor market and faster wage growth in that industry. A stronger labor market means employers must fill more openings from the ranks of the already employed, who have to quit their jobs, instead of hiring jobless workers. Similarly, faster wage growth in an industry signals workers that opportunities abound and they might get higher pay by taking a new job. Overall, wage growth has jumped from 2.5% to 3.3% since the beginning of 2018, and is going up even faster in some industries.

Most of the industries in which quits are rising faster are predictable. When unemployment is lower and job openings are plentiful, workers in construction, accommodation and food services, and government tend to leave their jobs more than workers in other industries. Meanwhile, the faster growth of quitting in health care and social assistance reflects a very tight labor market in which there are over two and half open jobs for every unemployed worker. Accommodation and food services sees higher growth in quits during tight labor markets and when wage growth accelerates because the industry employs a significant number of low-paid workers who may have opportunities for higher wages elsewhere.

Construction is an interesting case. Quits in construction tend to decline when wage growth in the industry is higher. Recently, construction wage gains have slowed, which may be responsible for the industry’s uptick in quits.

In a few industries, quits are declining. The fall in quits in real estate and rental and leasing and in finance and insurance may be due to weaker job markets in those industries. Over the past year, the unemployment-to-job-opening ratio rose in both those industries, signaling labor market weakness. These are high-paying industries and growth in quits in them tends to be low no matter what the state of the labor market.

Transportation workers may be quitting out of frustration with wage growth

Transportation, warehousing, and utilities, which has seen strong growth in quits, doesn’t typically experience such an acceleration as the labor market tightens. Yet quitting in this industry has been among the highest over the past year. What’s going on?

Stagnant wage growth seems to be the answer. Pay gains for workers in transportation and warehousing have not changed a lot over the past year, but have held steady around 2.9%. Workers may be frustrated they aren’t seeing the kind of bump-up in wage growth that is taking place in the rest of the labor market. The result: they’re quitting to seek higher wages.

In a tighter labor market, workers have more opportunities to boost their pay. Sometimes those opportunities are outside their current industries. If wage growth doesn’t accelerate in the industry they’re working in, they can head for the exits. Employers face a choice: they can match gains elsewhere and keep their employees or they can watch them leave. The cost of inaction might be high.

Methodology

The increase in quits is measured as an industry’s year-over-year growth in quits.

We looked at how responsive growth in quits in each industry is to the strength of that industry’s labor market, measured by its ratio of unemployed workers to open jobs.

We ran regressions to measure how much quitting accelerates when the labor market is stronger. First, we regressed the year-over-year growth rate of quits in each industry on a natural logarithm of the ratio of the number of unemployed workers to job openings in that industry, with industry and year fixed effects. The coefficient on the log of the unemployment-to-job-opening ratio is our measure of the sensitivity of quits to the health of the industry’s labor market.

The measure of an industry’s sensitivity to the health of the overall labor market is calculated using a similar regression, but the unemployment-to-job-opening ratio in the regression is the ratio for the nonfarm labor market.

We then observed whether an industry’s average wage growth had an effect on quits. For this regression, our list of industries was condensed due to availability of industry wage data. We regressed the year-over-year growth rate of the number of quits on the log of the overall unemployment-to-job-opening ratio and the year-over-year growth rate of the average wage for production workers in that industry.

Using the log of the quits rate as the dependent variable yielded similar results to those presented here.