Key points:

- Despite a solid bounceback, the Canadian labour market remains a ways from normal.

- Closing the remaining gap in the near term will require historically fast job growth, and in that regard, there are reasons for both optimism and concern.

- Among the reasons for optimism, job postings are returning to normal across a growing range of positions, and an eventual end to the pandemic will provide a welcome boost to struggling sectors.

- At the same time, several potential scars from the crisis could persist.

As a historically tumultuous year for the Canadian labour market comes to an end, what are the prospects for 2021?

Like with the pandemic itself, the main question is whether conditions can return to some semblance of normality. The recent surge in COVID-19 cases across most of Canada has made the outlook even murkier. Nonetheless, progress in taming the health crisis — especially the availability of effective vaccines — should eventually emerge as a major tailwind for the job market. However, what turns out as “normal” in a post-pandemic world might be different than what prevailed before.

Here are some questions I’ll be keeping an eye on in the year ahead:

1. Can the employment rate recover?

For the Canadian labour market, 2020 was a year for the record books. Each Labour Force Survey from March through June brought what was a new record employment change, with the first two down, and second two up. By November, over 80% of early-pandemic losses had been recouped. However, the initial drop was so sharp that Canadian employment remains 3.0% below its February level, further than the peak-to-trough decline during the 2008-09 recession.

Getting the employment rate back to its pre-pandemic level over the coming year will require job growth remaining in recovery mode for a sustained period. Starting in December, employment gains must average at least 76,000 jobs per month for the share of adults with a job to return to its February level before the end of 2021, assuming 1.2% annual population growth.

Such a pace would be slower than any of the monthly gains during the initial coronavirus rebound, prior to November. However, it would be quite rapid compared with the 26,000 average increase posted during the 2017-19 labour market expansion. If growth averages a somewhat slower, though still strong, 50,000 jobs per month, the employment rate wouldn’t reach its pre-pandemic level until late 2022.

2. How quickly can laid-off workers return?

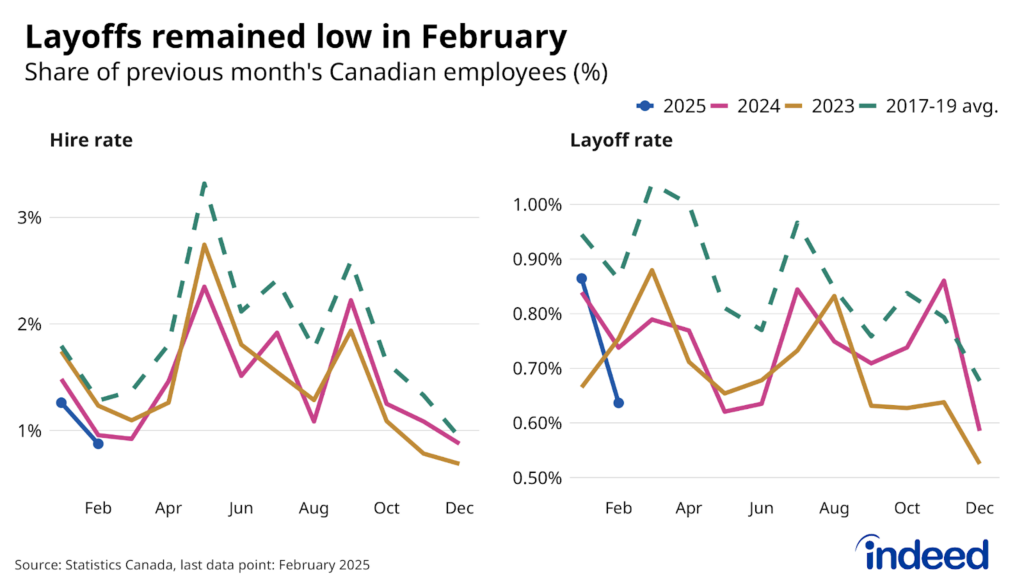

The labour market recovery has seen a swift return to work for some, and a more gradual — and, in some cases, painful — process for others. Roughly 40% of net job losses through May were temporary layoffs, affecting workers who expected to be recalled. The ranks of this group have shrunk substantially, but not to zero, still accounting for 27% of the remaining employment shortfall in November.

On the flip side are those who were permanently laid off, including some who’ve now been out of work for an extended period. Their numbers have also shrunk, but more slowly than their temporarily laid-off counterparts, who tend to be re-employed at faster rates. For overall conditions to get back to normal, this group must return to work relatively swiftly.

One encouraging sign has been a substantial, though still incomplete, rebound in employer demand. As of December 4, job postings on Indeed Canada were just 5% below last year’s trend after bottoming out at 49% below. This bounce-back in hiring appetite spans different wage levels and areas of the economy, including manufacturing, customer service, and tech.

3. When will the post-pandemic tailwind arrive?

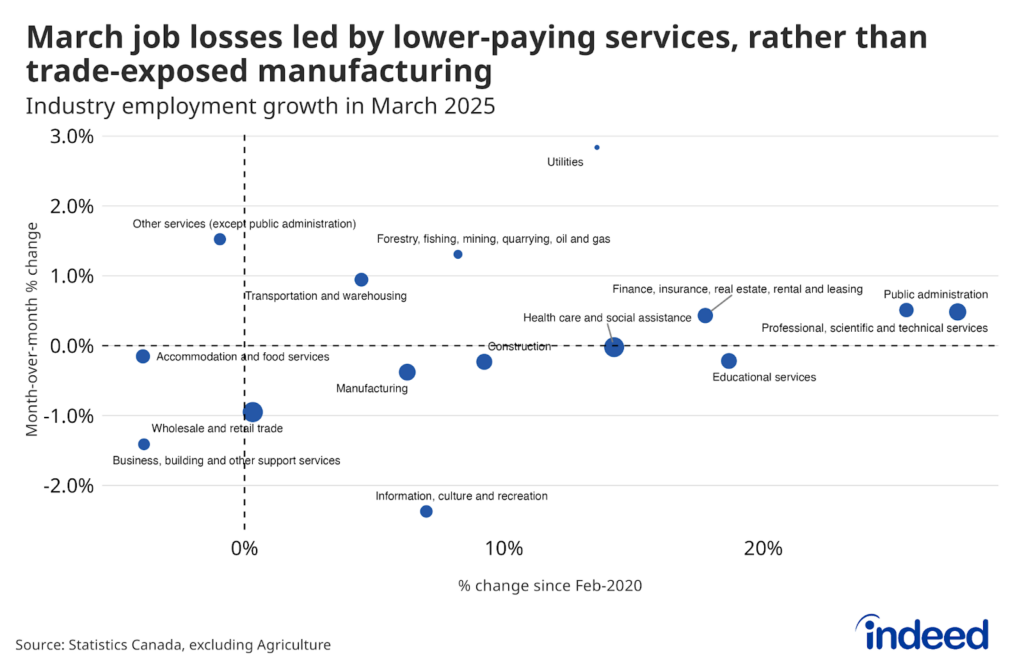

Despite the overall rebound, job postings remain weak in several pandemic-exposed sectors, such as food preparation and service, hospitality and tourism, and aviation. This fits with employment trends. As of November, sectors like accommodation and food service, as well as information, culture, and recreation are still far from February levels. These areas have also slid back since the COVID-19 surge this fall, a retreat that could extend into the winter.

It’s difficult to imagine these areas fully recovering as long as the health crisis remains. However, with vaccines eventually rolling out, demand for hotels, restaurants, and similar services could surge. Lifting the cloud hanging over these industries should be a major tailwind for overall employment growth, as they account for substantial share of the remaining net employment decline since February. Accommodation and food services alone accounts for 45% of the current gap.

Recovery of these sectors will also require people to jump at available employment opportunities. Job seeker interest on Indeed has shifted away from postings in lower-paying sectors, as well as those in roles not friendly to remote work. For instance, while postings in food preparation and service received 18% more clicks than the average Canadian job ad in February, by October they were getting 21% fewer clicks than the typical post.

We’ll be watching how job seekers respond as the health risks associated with such roles diminish. If employment and relative clicks per posting in sectors like food services, construction, and cleaning and sanitation remain down despite an end to the pandemic, it could be a sign that household supports like the Canadian Recovery Benefit are slowing the return of some unemployed people to work.

4. How severe is the permanent damage?

The longer a substantial employment rate gap remains, the greater the potential for persistent damage to the labour market, magnifying the importance of ending the pandemic quickly. This could play out in a few ways:

- Early retirements. Some laid-off older workers might retire earlier than they otherwise would. For instance, the labour force participation rate among women 55 and older is down 1.2 percentage points since February, more than most other groups.

- Stalled starts. Graduating during a recession has historically had lasting consequences, partly because it’s tougher to land entry-level, career-track jobs. Conditions look difficult for the class of 2020. Employment rates among post-secondary grads under 25 are down more than other youth, in contrast to those age 25-54.

- Self-employment struggles. Despite few job losses initially, the number of self-employed workers is now 4.7% below February levels. The share of the self-employed putting in less than half their usual hours has dropped, but also remains elevated, indicative of the challenges facing small businesses more broadly.

5. What will happen with wages?

Wages have been difficult to track during the crisis. One reason is that the concentration of job losses among lower-paying positions has substantially boosted the overall average. However, we can partially account for this effect by adjusting the underlying Labour Force Survey data to take into account the changing mix of jobs. (See methodology.)

After making these adjustments, hourly wages of 25-54 year olds have flatlined in recent months, compared with steady growth heading into the pandemic. With an uncertain outlook and unemployment still high, for many jobs, employers either haven’t felt much pressure to raise wages, or had the ability to do so. Employers project relatively subdued 1.2% wage growth over the next 12 months, down from 1.8% in February, according to the November CFIB business barometer survey.

The Canadian Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) program may be playing a part in keeping wages relatively steady. Weak revenue might have otherwise prompted some businesses to cut wages, but that downward pressure has possibly been offset by the government covering a substantial portion of their labour costs. How these policies play out in a broader economic recovery and interact with evolving labour market tightness will help determine the trajectory of Canadian wages in the year ahead.

6. What are prospects for the longer term?

The main story for the Canadian labour market in 2021 will revolve around how quickly the elevated number of unemployed workers can find jobs. This will be driven most importantly by the path of the virus. Whether the business climate encourages hiring and how government policy evolves will also be key.

The pandemic has also raised pressing questions about the future of work. In October, about one-quarter of employed Canadians were working from home, roughly double the pre-pandemic rate. This share is likely to fall as offices become safe again, but probably won’t return to the pre-pandemic baseline. How transformative this shift might be will depend not only on the number of people working remotely, but also on how many do so exclusively. Working from home a few days a week isn’t the same game changer as going fully remote.

People working remote exclusively may not have to live in the same city as their employer, and for certain roles, perhaps not even the same country. This increases opportunities for workers and businesses, but subjects both to greater competition. It also poses new questions for employers about how to manage a dispersed workforce, topics that are currently being deliberated.

The pandemic might also change business processes in ways that could affect the labour market. For instance, fewer people in the office probably means less need for workers to keep the workplace humming. Meanwhile, the surge in online shopping changes the retail hiring landscape.

A common theme in both the near term and the longer run is that it’s tough to see the shape of things to come as long as the pandemic persists. The sooner the fog lifts, the sooner we’ll be able to gauge how much of what changed in 2020 was temporary and how much was more permanent.

Methodology

We adjust for how changes in employment have impacted average hourly wages of employees of ages 25-54 by using the Labour Force Survey public-use microdata to hold the composition of workers fixed at their February 2020 shares of employment across three dimensions: industry, occupation (both at their two-digit classification levels), and job tenure (bucketed into three groups: six months or less, seven to 24 months, and over two years).