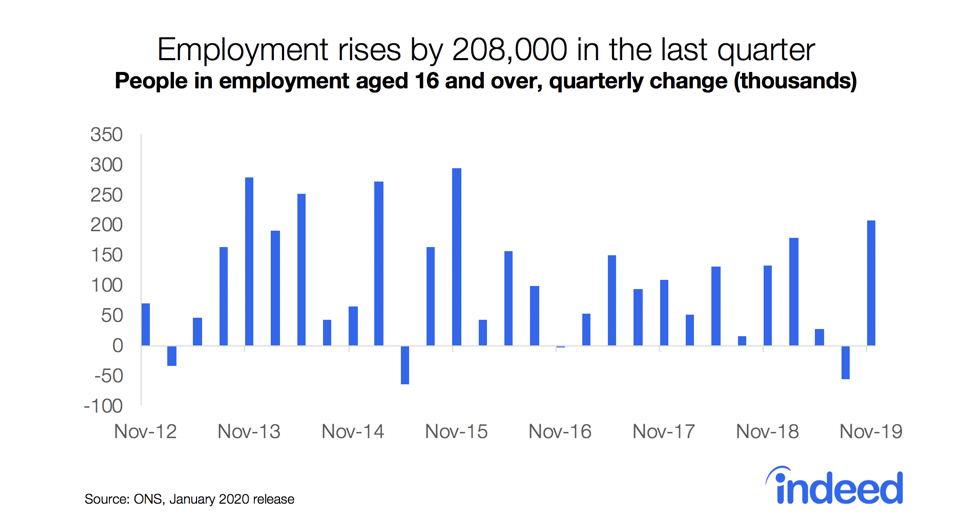

The booming UK labour market broke many records in 2018 and, on the surface, things look great for workers. An unprecedented three-quarters of the working-age population is employed, while the unemployment rate hit a 43-year low. The total number of unemployed people remains low relative to the number of vacancies. All this is good news for workers because rising competition for staff should help shift the balance of power between employees and employers in their favour.

It is not just the quantity of jobs, but also the quality that matters. By that standard, 2018 brought good news as well. Although zero-hours contracts get a lot of attention, their number is falling. Virtually all the employment growth over the past year came from full-time jobs, while the number of people stuck in part-time work because they could not find a full-time job is the lowest in nine years. Overall, fewer people say they want longer working hours than at any point since 2009. Better yet, financial rewards from work improved as well. Thanks to the tension between strong employer demand for staff and limited expansion in the size of the labour force, pay growth accelerated to a 3.3% annual rate.

On the other hand, the tight labour market is a rising source of frustration for employers and many businesses report hiring difficulties. The proportion of new hires coming from employment has risen above its level before the financial crisis of a decade ago. That means employers have to compete for recruits.

The year has been a disappointment in one other respect — improvements in workers’ living standards have not been as big as many have hoped for. That is in part due to Brexit. The process is still entangled in a political quagmire, with research suggesting that Brexit-related uncertainty may already have reduced investment and output even before the UK has left the European Union. At the same time, falling sterling has stoked inflation.

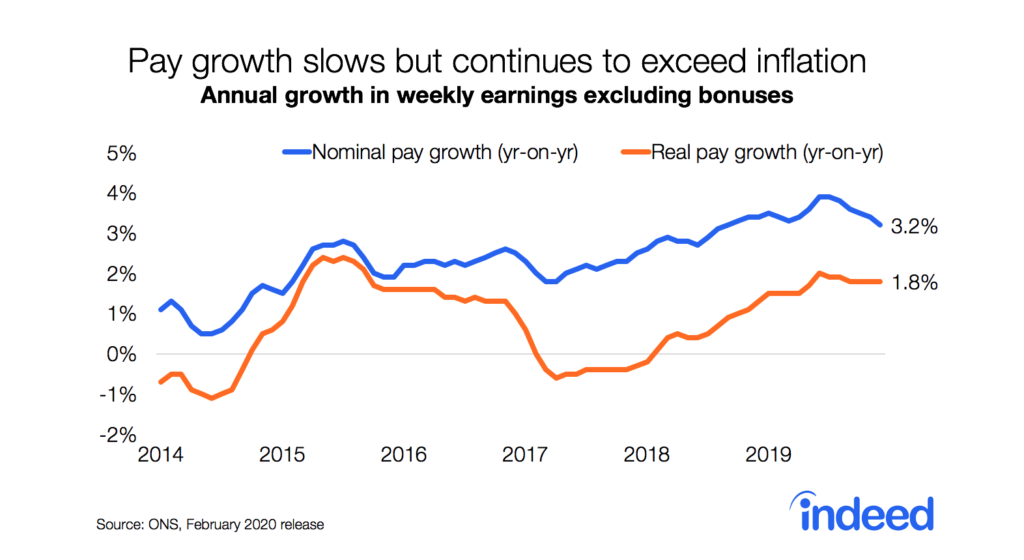

Even though pay is nominally growing at its fastest rate in 10 years, rising prices of goods and services have kept the purchasing power of the average employee’s weekly salary only £4.50 higher than a year ago — barely enough for a caramel latte. This is prolonging Britain’s lost decade of wage growth. If real wages had continued growing at the pre-crisis rate, the average employee would currently be earning approximately £130 a week more.

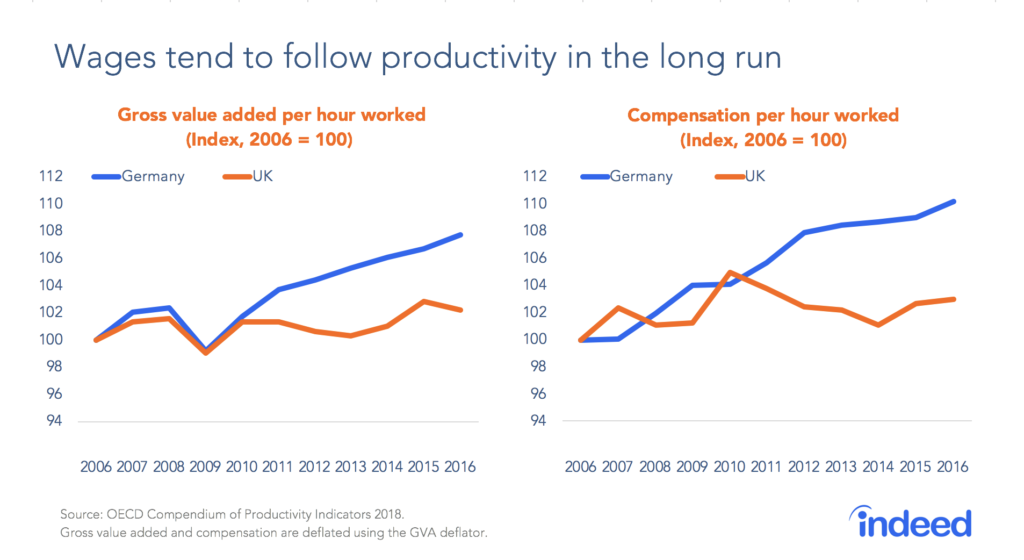

Stronger productivity growth is required for higher, sustained growth in real wages. And while productivity, measured as output per hour, now exceeds its pre-crisis peak, the growth rate of around 1% forecast by the Bank of England for 2018 and 2019 remains below the pre-crisis pace of productivity improvement. All this casts doubt on the post-Brexit economy’s ability to generate sustained gains in productivity and, as a consequence, higher living standards for years to come.

What’s next for the labour market?

Here are three things to watch as we head into 2019.

Wage growth. In real terms, we are unlikely to see sustained, rapid growth in pay until we see faster productivity gains. That is because rising productivity is one of the most important determinants of wage growth in the long run. The charts comparing the post-crisis experience of the UK with that of Germany illustrate this relationship. In Germany, the pace of productivity improvement recovered after the crisis, but not in the UK, with pay following productivity’s lead in both countries. Developments on the productivity front are something to monitor closely in 2019.

Brexit. Leaving the EU is likely to disrupt many sectors of the UK economy, including those that rely heavily on European workers. The magnitude of the disruption will depend on the details of the final Brexit agreement, which is making its way through a tortuous political process leading up to the March 29 deadline. In the longer term, the trading relationship between the UK and the EU after the Brexit transition period will be crucial. Will trade continue to be nearly frictionless or will it suffer economic and administrative barriers? Will migration policy support or hinder growth? The answers to those questions will determine the extent to which Brexit affects the economy’s productivity and thus the living standards of UK residents.

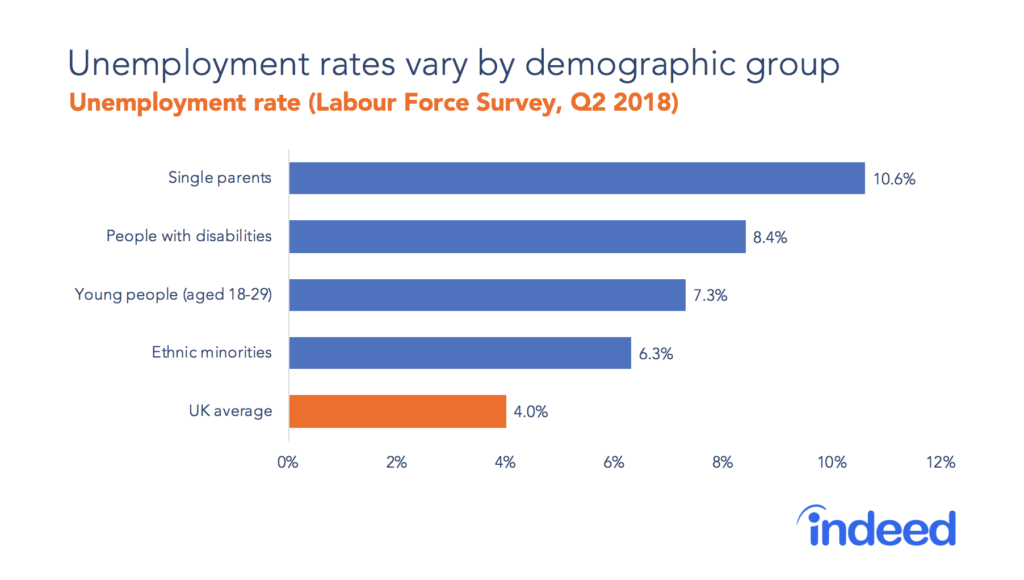

Hiring challenges. Low unemployment, falling migration and uncertainty about post-Brexit migration policy mean that businesses in many sectors are finding it increasingly difficult to hire staff. To recruit the workers they need, will employers tap more into under-utilised demographic groups? Young people, single parents, minorities and people with disabilities are less likely than average to be part of the labour force and their unemployment rates are above average. Whether employers manage to attract those groups into employment through higher wages or benefits — or whether they respond to hiring difficulties in other ways, like investing in automation — is a trend to watch in 2019.

How the labour market develops next year will partly depend on the exact form Brexit takes. As always, the devil is in the details. But low real wage growth and employers’ ability to attract underemployed groups into work are among the key things to watch regardless of how Brexit plays out.