When it comes to the British labour market, it may be hyperbole to use Dickens’ line about the best of times, the worst of times. Nevertheless, the market sent decidedly mixed messages in 2017. With the employment rate close to its record high, the jobs picture looks exceptionally strong despite a recent slowdown. But wage growth, adjusted for inflation, remains disappointingly weak after turning negative over the past year.

Meanwhile, Brexit’s impact is already being felt in at least one part of the labour market: The most recent net migration numbers showed a drop of over 100,000 people moving to Britain in the year ending in June 2017.

As 2017 draws to a close, the outlook for the UK labour market looks uncertain. Here are some economic signals we’re tracking:

- Job growth shifted toward full-time rather than part-time or temporary jobs over the past year–and that’s good news for British workers.

- Stagnant pay is squeezing worker living standards and signals are contradictory regarding the trajectory of future wages. On one hand, increasing labour market tightness could soon fuel higher wages. On the other hand, downgrades to the productivity outlook present a less optimistic picture.

- On top of that, a sustained decrease in migration, especially from the rest of the EU, may further strain the UK economy.

Let’s take a closer look at these signals to see if they provide clues about where the labour market is headed in the year to come.

More and better jobs

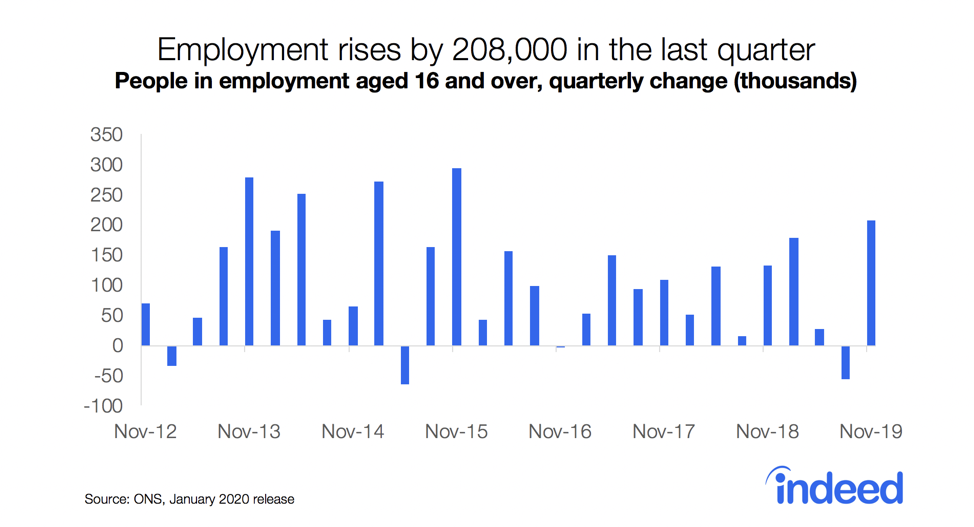

Over the past year, on a net basis, virtually all job creation came from full-time positions. The number of workers on temporary contracts kept falling, while self-employment grew at a much slower pace than in 2016. The number of people on contracts that do not guarantee a minimum number of hours–so-called zero-hour contracts–fell, though it is still high. In addition, higher-than-average growth in the employment rate of people age 25-34 in the year ending September 2017 probably points to broad-based labour force gains.

Indeed job search data confirms that, as the labour market tightens, British workers increasingly are looking for jobs with regular hours and predictable pay. Over the past year, the share of searches for “full-time” on indeed.co.uk has jumped a third, while the share of searches for “part-time” has increased only 8%.

With the unemployment rate at its lowest level since 1975 and the proportion of people working reaching a record high, UK employment trends were strong in 2017. However, the latest Office for National Statistics figures call for caution. The number of people at work in Britain recently dropped for two successive quarters for the first time since March 2013, while inactivity increased. That prompted some commentators to suggest that the “UK jobs boom” may be coming to an end.

The missing elephant in the room: pay growth

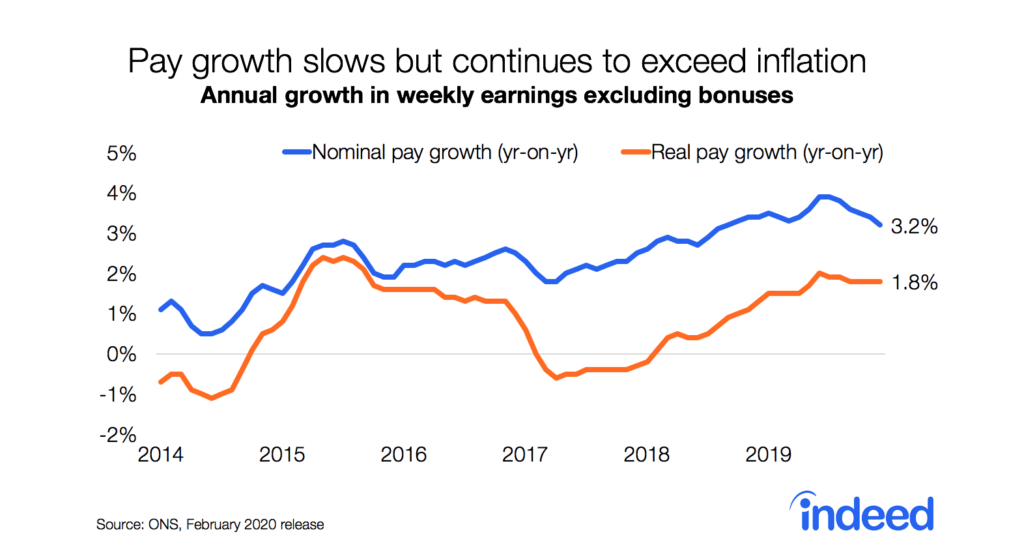

So far, strong job creation, a tightening labour market and the improving quality of available jobs have done little to boost the performance of wages. In 2017, rising inflation offset small nominal wage gains, continuing the extended pay squeeze on British workers. Real annual wage growth, excluding bonuses, turned negative in March and stands at -0.4% for the year. A decade of stagnating real wages means that workers in the UK are today earning only slightly more than they were in 2006 after accounting for changes in prices.

At least the hardest pressed are getting some relief. The fall in real wages is less severe at the bottom of the pay scale thanks to a boost from the National Living Wage. This is especially apparent in sectors like agriculture and support services, which are enjoying real gains. Nevertheless, for the overwhelming majority of British workers, salaries are falling in real terms, with the service sector taking the biggest hit.

Labour productivity–output per hour of work–is an important determinant of pay growth. Unfortunately, there is not a lot a room for optimism there, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) latest forecast revisions. OBR now expects productivity growth to pick up only a little and to remain significantly below its pre-crisis rate for the next five years–the biggest downgrade ever reported for this measure. The gap between output per hour and its pre-crisis trend would rise to 27% by the beginning of 2023, up from 21% today, if these projections are borne out, according to an ONS estimate. That means that today’s wage weakness may persist well into 2018.

Fewer people are moving to the UK

In the year ending June 2017, net migration to the UK fell by a third. A decline in EU net migration accounted for over three-quarters of the drop, the ONS reported. Indeed data on international job searches within the bloc of EU15 countries–the core group of the oldest EU member states–show that the share of searches directed at UK jobs now stands at 31.8%, down from 37.3% two years ago. That was the biggest drop in interest by European jobseekers registered in the EU.

Falling migration was especially pronounced in London and among EU-born graduates, an analysis by the Resolution Foundation found. Even though the UK hasn’t left the European Union yet, a mix of improved Eurozone labour market conditions, the falling value of the pound and Britain’s decreasing attractiveness as a destination for EU workers are already affecting the labour market. For better or worse, the future UK labour market will have to adjust to significantly lower levels of migration from the EU.