Today, migration to wealthy countries is on the rise. In fact, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reported that 4.8 million people moved to its member countries in 2015 — 10% more than in 2014. This is controversial due to the impact of migration on both origin and host economies.

For instance, countries that experience significant net emigration can in the long-run be exposed to the threat of brain-drain, a lack of economic dynamism and over-reliance on remittances from abroad. But migrants can be a boon for countries that attract them. Studies have shown that immigration accounted for half the growth in the working-age population of advanced economies between 1990 and 2015. Despite the potential for negative effects on the wages of native workers in similar jobs or with similar skills, and a possible increase in social tensions, both high- and low-skilled migrants have generally been found to raise productivity and GDP in the destination countries.

The positive contribution that immigrants can bring to an economy in aggregate is well documented. Most economic research shows that medium and lower skilled foreign workers boost the labor supply in countries where the local population is ageing quickly with, as a rule, a generally limited impact on wage levels. Even if some disagreement exists about how much native-born workers in similar jobs and with similar skills are hurt by competition with immigrants and the consequent downward pressure they may bring on natives’ wages (particularly in economic downturns) research on this topic has usually concluded that high-skilled workers from abroad end up raising native workers’ pay — as long as they complement domestic employees more than they compete with them.

Across the world, however, governments of countries that have historically benefited from openness and immigration, at least at the aggregate level, are increasingly viewing it more as a threat than an opportunity. For example, support for Donald Trump and Brexit (where concern over immigration is widely recognized as having played a role in voting outcomes) was stronger in areas with fewer immigrants but larger recent increases in the local immigrant population.

In this article we make no attempt to resolve these complex debates. Instead, we will analyze millions of cross- border job searches conducted on Indeed websites in 49 countries between April 1st and August 31st, 2016 to show how a country’s participation in the international labor market is an indicator of economic success as well as one of the main components of it.

Participation, we show, is part of a positive feedback loop in which prosperous countries that are taking an active role in the global exchange of job seekers tend to have higher incomes and a higher concentration of job opportunities. We will point to economic literature that suggests that this is in part the result of their participation in the exchange of workers and their talent, capital and ideas. Reducing a country’s level of participation is understandable when workers in many countries see (or at least perceive) increased competition from immigrants. However, there may be a negative risk in the long-term, as such an approach has the potential to break this virtuous circle — with a negative impact on both native and immigrant workers.

Countries with higher incomes participate more actively in the international labor market

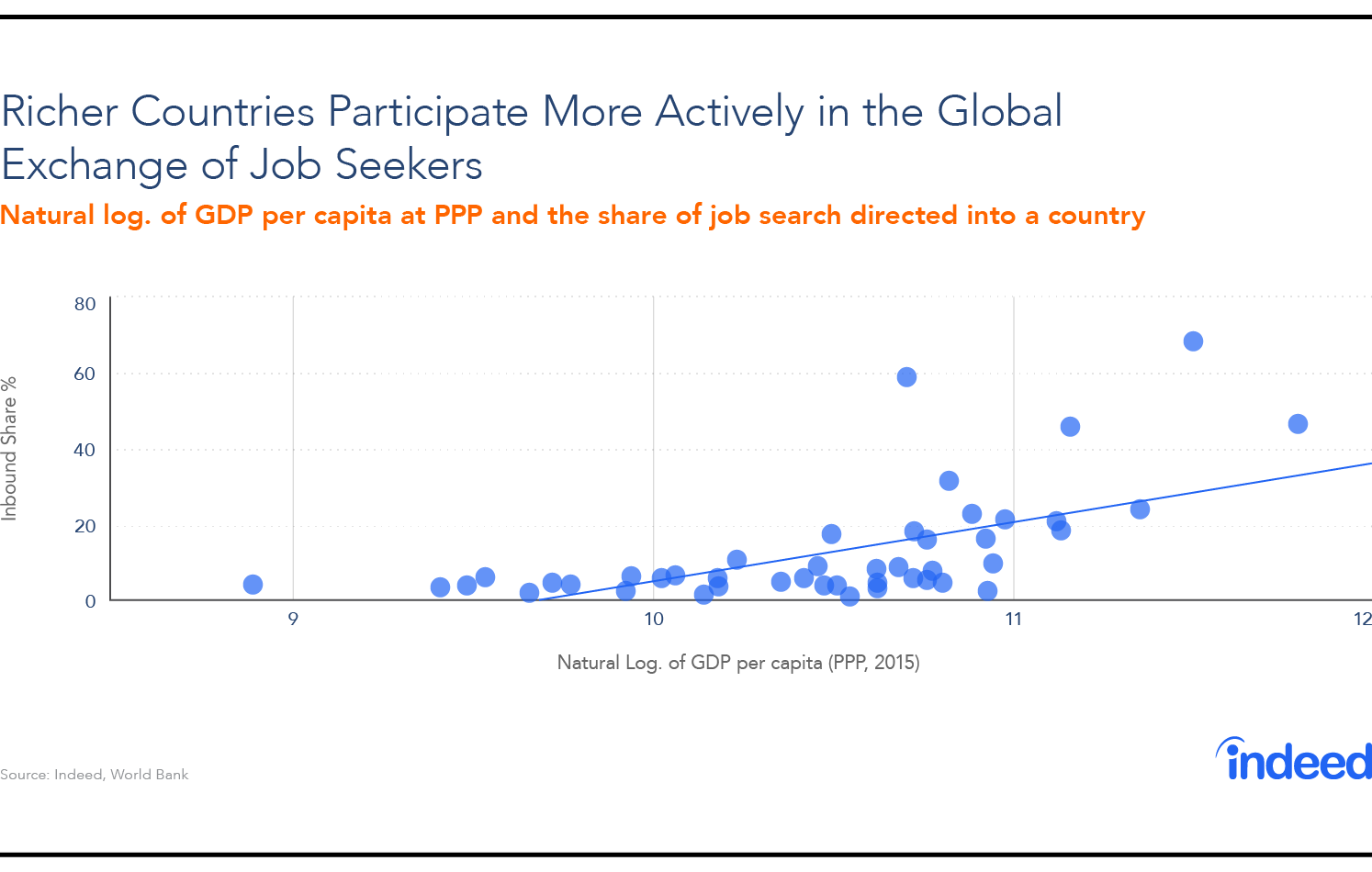

In the chart below we see that relative income (measured by GDP per capita adjusted by Purchasing Power Parity) is positively correlated with our measure of participation based on search traffic in and out of a country, which serves as a proxy of how much a country’s labor market is embedded in the flow of job seekers across borders.

Nations with higher incomes tend to be very active participants in the global exchange of labor as they both receive and send larger shares of cross-border job seekers. Hence, more than a measure of how much a country imports or exports job seekers, the flows of job seekers looking in and out of a country offer an indication of how embedded a given labor market may be in the global exchange of job seekers.

It is not hard to imagine why high income is associated with greater participation in the global exchange of job seekers. Richer countries have more work for job seekers of all skill levels, they offer better wages and standards of living, and so are attractive to foreign workers seeking a new location in which to live and work. The OECD group of mostly rich economies offers the best example: they constitute less than a fifth of the world’s population, but host two-thirds of high-skilled migrants.

Participation, however, is a two-way street, with job seekers from higher income countries more likely to search abroad as they are more likely to have the means, education (and passports) that enable them to take advantage of the available cross-border opportunities. However immigrants and emigrants are not the only beneficiaries. The economies that host them also gain from this movement.

Higher levels of participation in the cross-border flows of job seekers is not only a characteristic of a select group of wealthy democracies. Countries based on radically different economic and political systems — such as the resource-rich Gulf countries — have also significantly benefitted from foreign labor in recent decades.

In these countries, the high demand for labor at different skill levels combined with such factors as their small domestic labor forces, low taxation and high wages has resulted in the arrival of large numbers of foreign workers from both advanced and less-developed economies. As a result, their economic growth has been dependent on foreign labor and, as our data shows, they are associated with the highest shares of job search crossing their borders in our sample.

Opportunity and participation in the global labor market go hand in hand

The concentration of job opportunities is another important driver of a country’s participation in the global exchange of job seekers.

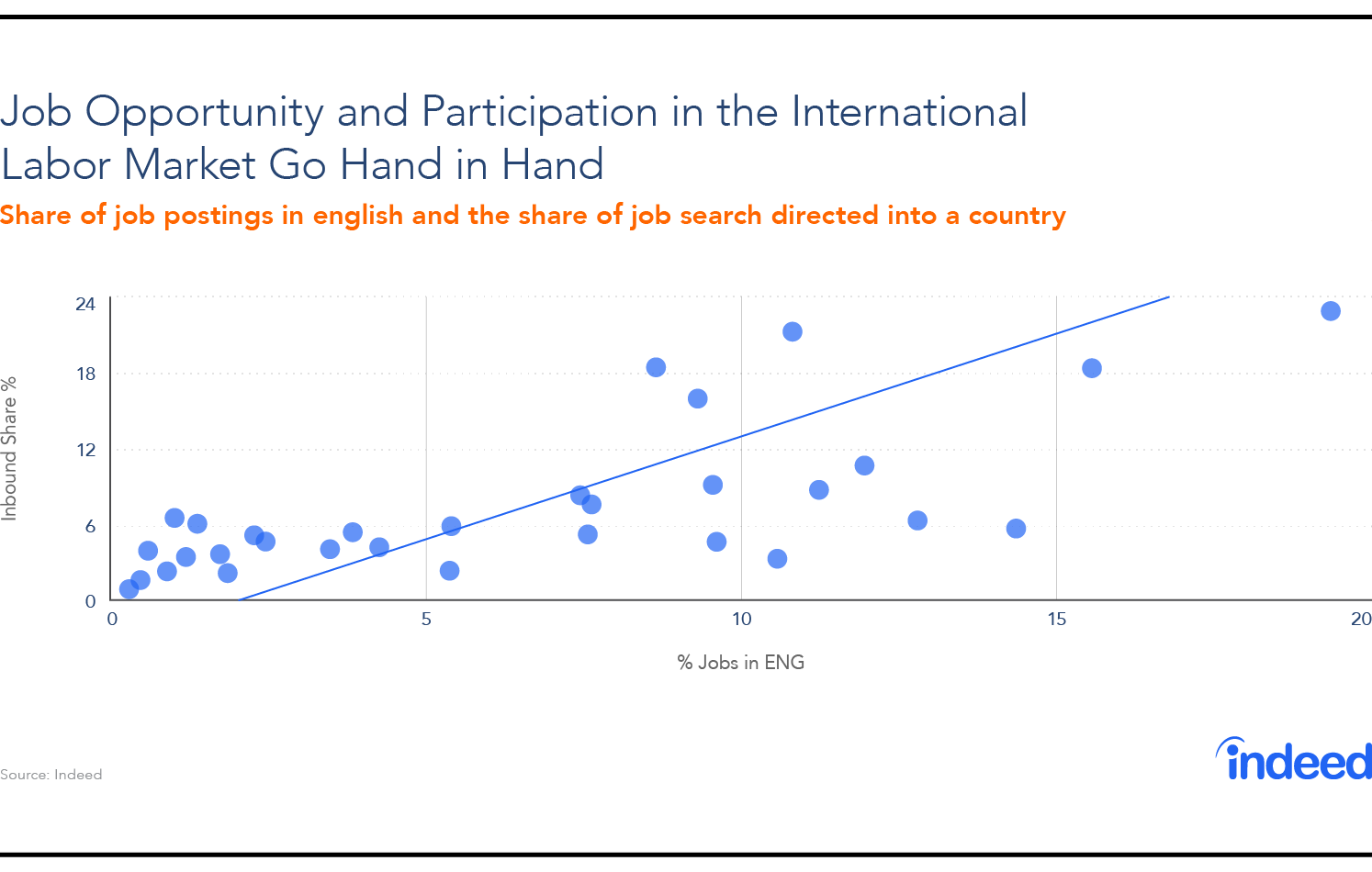

Previous research from the Hiring Lab has shown that job seekers are responsive to local economic conditions, with more people searching in locations where there are jobs available and fewer people searching in locations where opportunities are scarcer. Following a similar dynamic, we found that people on Indeed look for jobs in locations where opportunities open to foreign talent are most widely available, and since they may not always be fluent in any language other than their mother tongue and (perhaps) English, linguistic factors play an important role. In particular, job ads in English make it easier for candidates to consider and apply to jobs abroad and the prevalence of jobs advertised in English serves as an indicator of how open national employers are to international candidates.

A strong positive association can be found between the participation of a country in the international labor market and the number of job postings in English as a share of the total. Interestingly, the correlation remains even when we drop the English-speaking countries in our sample and only focus on countries where less than 20% of jobs are posted in English, as we see in the chart below.

Countries with a higher percentage of job postings in English, where the local language is not English, may be signalling their receptiveness to foreign workers. This indicator might also tell us something about the characteristics shared by cross-border job seekers.

According to a comprehensive report recently released by the McKinsey Global Institute, of the 247 million people who do not live in their country of birth 35% are high-skill migrants with tertiary education or above. This is often much higher than the share of university graduates in their home countries. Between 1990 and 2010, high-skill migrants residing in OECD countries increased by 130%. The fact that cross-border job seekers on Indeed tend to be attracted to jobs posted in English supports the argument that prospective migrants searching for jobs abroad tend to be more skilled than the average job seeker, as jobs that require English tend to be in international industries and are more likely to be white collar professions.

Evidence from Indeed data shows that international job seekers are more likely to show interest in relatively higher skilled jobs with respect to domestic job seekers. For example, EU-based job seekers searching for jobs on indeed.co.uk in October 2016 were between 2.2 and 2.7 times more likely to click on jobs that are classified by Indeed as Science, Analytics, Technology/Software, Marketing or Legal than domestic job seekers.

This suggests then any policies aimed at making it more difficult for foreign workers to take up a job in a country have the potential to reduce the pool of available qualified candidates for firms located in that same country. It is not clear how easily these gaps could be filled by training or upskilling natives. Policy makers should therefore consider the risks carefully.

Conclusions

Attractiveness and participation of a country in the international labor market are an indicator of economic success as well as one of its key components, as economic research suggests. Our analysis shows that countries open to the global exchange of job seekers are richer, more successful and have a higher concentration of opportunities open to international candidates.

This does not rule out the possibility that immigration may have a negative impact — in terms of increased competition and downward pressure on wages — on specific groups of the population or regions of a country. Yet, it is interesting to point out that not all prosperous destinations are equally attractive for potential migrants. A complex mix of factors — ranging from immigration policies to local economic conditions — affect the degree of a country’s participation in the global flows of workers.

Methodology

We measure participation in the international labor market with the “Inbound share” which captures the flow of job search coming from outside the country and looking for jobs in a country as a share of that country’s total job search traffic on Indeed. This measure is highly positively correlated with the “outbound share” which is why we consider this a measure of participation, not just attractiveness for in migration. For a more detailed explanation of our choice of indicator see the Appendix.