With only two weeks of 2016 left to go, it’s a good time to take a look back at what happened in the UK labour market over the past year.

Solid job growth along with a sustained decline in unemployment, pay rises for low earners and a continued steady supply of skilled EU workers all made the good news. However shadows are also looming: stagnant wages, declining productivity, a potential deceleration in economic growth and headwinds related to Brexit will continue to pose threats to the performance of the labour market in the coming year.

In addition, broader global trends in the world of work that have recently moved to center-stage in the debate on the future of labour may bring additional challenges. Above all, shifts associated with the increase in freelancing, contracting and other “gig” work, as well as the threat of job automation are expected to bring further uncertainty for workers in the UK and other advanced countries across the globe.

Let’s take a deeper dive.

A year of solid employment growth

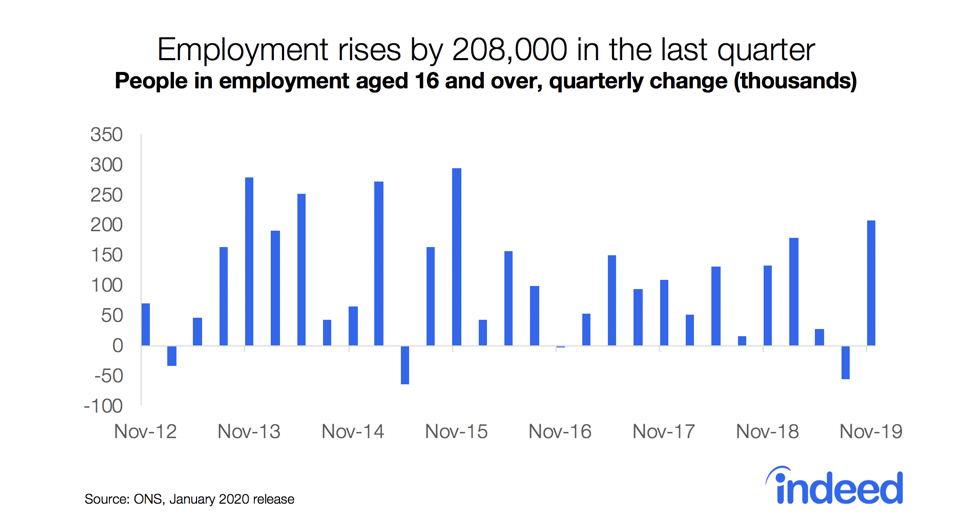

First, the good news: Aside from a few ups and downs, the number of people in work in the UK has steadily increased over the past five years. 2016 continued this trend and was a generally positive year for employment—even though the pace at which jobs were created eased somewhat with respect to previous years.

This may in part be due to the employment rate, which peaked at an all-time high in May 2016, remained at that plateau for months and then in October declined, but only slightly. In addition, the unemployment rate fell back to its pre-recession levels by the end of 2015 and has since fallen even further, reaching 4.8% according to the most recent figures from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) (August-October 2016).

Wages of the lowest-earners increased at the fastest rate in almost 20 years

The introduction of the National Living Wage (NLW) in April delivered a sizable pay boost to those at the bottom of the wage ladder. Between 2015 and 2016, weekly earnings for workers in the bottom 5% grew at a healthy rate of 6.2%—2.8 times faster than those of the median.

Although the NLW has not been met with approval from all sides, any potential detrimental effects on firms’ hiring decisions caused by rising labour costs have yet to materialise. Evidence suggests that—at least for now—most employers are choosing to absorb the extra costs by raising prices or accepting slimmer margins while only a small proportion have cut jobs.

In addition, even though NLW-induced wage gains for the lowest earners were not evenly distributed across regions, the policy has, overall, contributed to a slight narrowing of the wage gap both across and within regions, with positive repercussions for wage inequality.

The UK is still the destination of choice for EU job seekers and workers

Hiring Lab research published in March found that the UK is the top destination for job seekers in the EU. In fact, we saw that Britain receives about three times as much interest from jobseekers based in other EU countries as either of the next two most popular destinations—Germany and France. Even in the months following the Brexit vote, the UK remained a popular destination for job seekers across Europe. Job search patterns on Indeed reflect the official migration statistics: the latest ONS data covering the three months following the Brexit vote show that net migration remains around record levels. The inflow of EU citizens is also at historically high levels and there has been a significant increase in people looking for work, particularly from the EU.

Although this influx of foreign workers is controversial within the UK, the positive contribution that EU immigrants bring in terms of a boost to the labour supply is clear—in Q4 2015 the employment rate for those born elsewhere in the EU and living in the UK was 70%—well above the equivalent rates for those born in the UK and in non-EU countries (both 60%). Post-Brexit, a change in the EU-UK relationship aimed at lowering the levels of net inward EU migration could, however, change all this. The most obvious consequence of a “hard Brexit” would be to depress labour supply in the market with negative consequences for economic growth.

As employment peaks there are warning lights on the horizon

Now let’s take a look at labour market developments in 2016 that were less positive—those looming shadows I mentioned at the start.

While the UK’s employment performance has been remarkable—among the G7 economies, only Germany has seen faster prime-age employment growth between 2007 and 2017—some initial signs of a weakening are on the horizon. For one thing, the employment rate has declined between August and October after remaining level for the previous four months. This means that the latest two falls in unemployment (registered for the periods July-September and August-October) have been driven by an unwelcome increase in economic inactivity as the number of people who stopped looking for jobs and dropped out of the labour force is at its highest in almost two years.

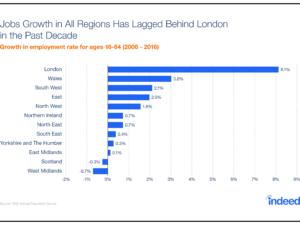

Also, labour market performance at the regional level has been much more varied. Job growth in all regions has lagged behind London, with the Midlands, Yorkshire and Scotland showing the poorest performances.

Wage and productivity growth: the missing pieces of the labour market puzzle

The most worrying signs on the horizon for the labour market are associated with the sluggish performance of wages and productivity. Both have been stagnating for some time, but the UK’s productivity performance is one of the worst among advanced economies. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), labour productivity growth was only 2% from 2010 to 2015 in the UK, the smallest increase in the OECD group after Hungary, Italy and Greece.

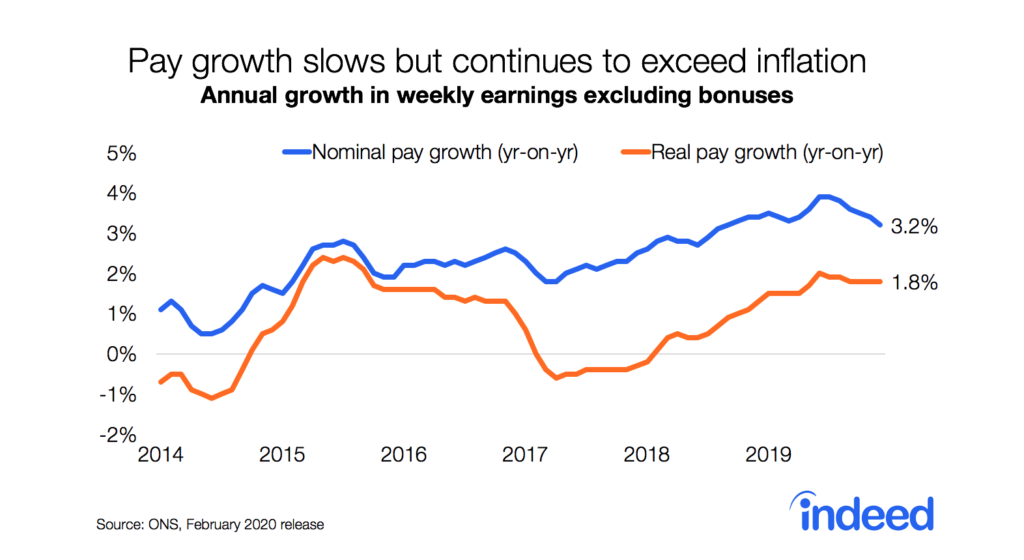

The performance of real wages has, to some extent, been even more disappointing. Average earnings after adjusting for inflation are still below their 2008 levels. This in itself is unprecedented in recent decades. Real earnings rose on average by 2.5% between 2001 and 2008, but they have declined by 0.7% since then. Growth could slow down even further in the coming year when CPI inflation is expected to move above the Bank of England’s 2% target, up from the current 0.9%.

In addition, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in its latest forecast revisions expects average real wages to still be slightly below their 2008 level in 2021. This has prompted some commentators to talk about a “a decade of lost wage growth” as British workers face their worst decade for pay in 70 years. Real wages in the UK were hit badly after the financial crisis and the OBR’s forecasts suggest the outlook has darkened again since the Brexit vote.

The disappointing figures for wage growth partly reflect weak productivity — the ultimate driver of wages—that is now anticipated to increase less quickly than was expected back in March. Similar experiences in many Eurozone economies—Germany above all—have prompted the European Central Bank’s governor Mario Draghi to state that “the case for higher wages is unquestionable”.

As Brexit looms, its impact on the labour market may be bleak

Uncertainty brought about by the Brexit referendum contributed to a dampening of hiring sentiment in the labour market. Even before the referendum, Indeed Industry Employment Trends, a monthly index of UK job postings, showed declines starting in February 2016, signaling a deterioration in British employers’ willingness to hire that is only just now beginning to materialize in official employment figures.

Indeed data also showed that in the 48 hours following the announcement of the referendum results, the share of UK jobseekers looking for opportunities in European countries and in other non-EU English-speaking countries was significantly higher than the average in the days prior to the vote. In the months that followed, interest in jobs outside the UK remained at elevated levels.

Whether or not such an increase in interest will translate into a surge in emigration to EU and other English-speaking countries along with a possible decline in EU citizens’ immigration to the United Kingdom remains to be seen. Even the most up-to-date official migration statistics date back to June and they do not show any significant impact of the Brexit referendum on inflows or outflows during the run-up to the vote.

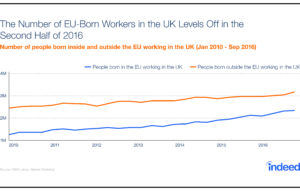

That said, one early indicator of sign of a possible impact of Brexit on the British labour market may be visible in the ONS November labour market release, which saw the number of workers born in the EU in employment level off, while the number born outside the EU increased, reversing previous trends. Similarly, the Department for Work and Pensions reported that the number of National Insurance Numbers registrations to EU nationals has flatlined over recent quarters, reversing the generally upward trend since 2010.

In its forecast, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects EU migration to decline much further. More specifically, it predicts that the post-Brexit drop could cost the UK economy £6bn a year—and this would just be in terms of the direct impact of having fewer workers. The downward revisions of the 2017 GDP forecast also point towards a weaker economic outlook that has the potential to negatively impact the labour market in 2017.

A year of mixed signals from the labour market

As the end of 2016 approaches, the UK labour market finds itself in better shape than most economists would have predicted even a few months ago. It continues to tighten and to deliver solid jobs growth, even as wages and productivity continue to lag.

With higher price inflation on the horizon, however, even a strong labour market may struggle to deliver the wage improvements badly needed by British workers. While there is still not enough evidence to indicate that Brexit has had a major impact on either the labour market or the economy just yet, it is also unlikely that the increasing uncertainty it brought will aid productivity growth in the short run.

Much will depend on the outcome of the negotiations that will shape the new relationship between the UK and the rest of the EU in the future. For the time being, however, a myriad of factors coming together may make for a bumpy road ahead in the British labour market.