Key points:

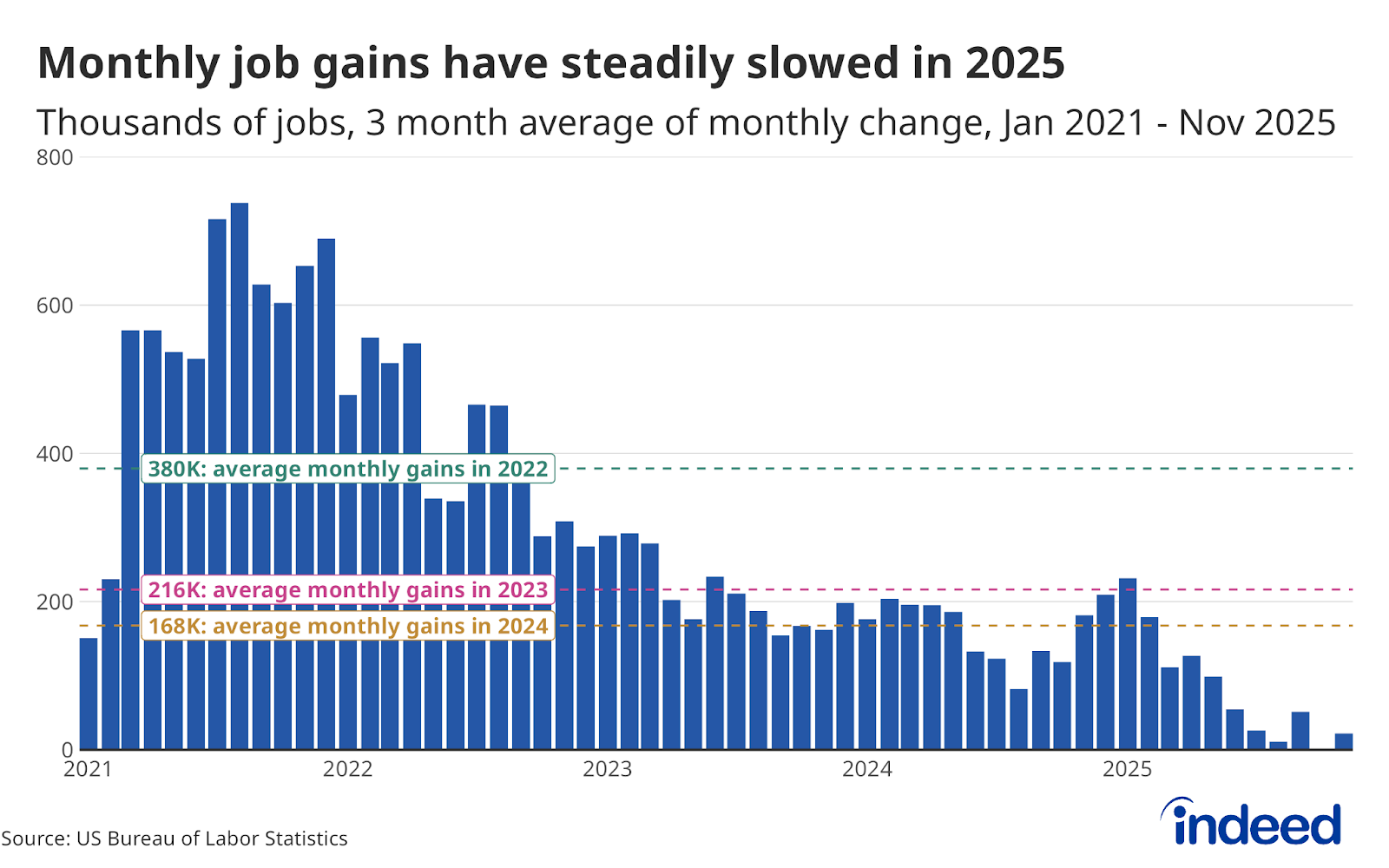

- Employers added 64,000 jobs in November, following a net loss of 105,000 in October, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- The unemployment rate rose to 4.6% in November. Unemployment data for October was not published.

- Average hourly earnings for workers rose by 3.5% year-over-year in November.

Today’s incomplete and unconventional jobs report may always need an asterisk attached to it, but it still paints a sobering picture of a job market that may officially be turning frigid after a prolonged cooling period. The combined two-month report shows notable declines in employment in October as tens of thousands of government employees who had remained on payrolls through the summer finally came off as their buyout deals took effect. Job growth rebounded in November, but was weak overall, with continued growth in healthcare and certain trades jobs, and weaknesses essentially everywhere else. Certain healthcare roles now account for virtually all of this year’s job growth, a worrisome concentration that is helping to push up unemployment overall as non-healthcare workers struggle to enter the market.

Today’s unique release contains payroll employment data for both October and November, but lacks October data from the household survey. This means no unemployment or labor force data will ever be released for the month, a first for the BLS. And the methodology used for both months was different from “normal” as a result of the government shutdown. The end of the federal government’s deferred resignation program led to the official separation of 162,000 federal government employees. Private establishments added 52,000 jobs in October, which was far less than was needed to offset the large federal employment loss.

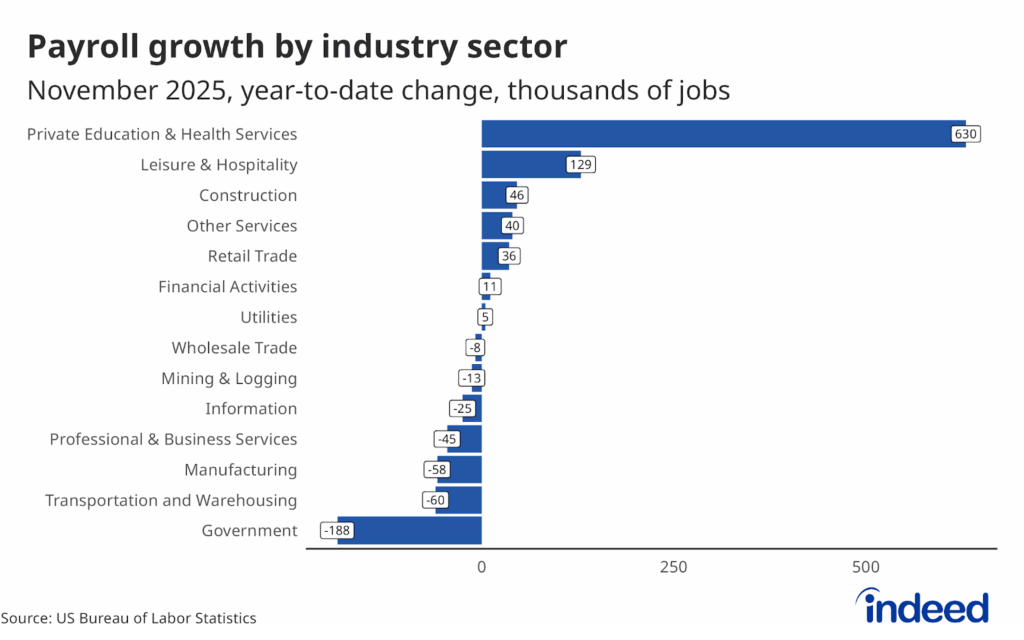

The available data show that job growth itself has become highly concentrated. The economy as a whole has added 499,000 jobs on net since the start of the year — and 630,000 of them have come from the private education and health services sector. Put another way, without this sector, the overall labor market would have actually lost 131,000 jobs so far in 2025. Needless to say, this limited job growth is very problematic, especially for workers in other sectors who don’t want or are not qualified for these jobs. Sidelined workers are showing signs of turning to temporary or gig work to get by — the share of workers with multiple jobs has risen to 5.8%, the highest level in more than 25 years, representing almost 9.5 million workers.

Manufacturing, transportation and warehousing, and financial activities jobs all saw declines again in October and November, a pattern that has become commonplace this year. It is difficult not to attribute at least some of this weakness to tariff policy, and potentially even more to the uncertainty surrounding it. Manufacturing sub-sectors, including machinery manufacturing, electronics manufacturing, and transportation equipment manufacturing, have each lost more than 10,000 jobs in the last year and are all relatively exposed to tariffs on both their final goods and the intermediate goods used in production.

Outdated data collection methods have been explicitly called into question by Fed Chair Jerome Powell lately, raising fears that recent job creation numbers could be overstated by around 60,000 per month. The BLS will reportedly update its so-called “life-death model” of business creation and demise in February 2026. Until we observe the new methodology and updated payroll estimates, we should remain guarded in our interpretation of these data. In a best-case world, the labor market continues its languid growth, with a small set of sectors generating a very large percentage of jobs. However, it is also possible that we have lost jobs in many of the months this year, and future revisions will present an even bleaker view.