Key points:

- Working-age migrants who moved to the United States in the past five years were almost 18 percentage points more likely to be employed than native-born individuals, while also being more likely to be actively seeking employment.

- Migrants reported more confidence in their ability to find a job within the next month.

- Migrants were systematically more positive about the future labor conditions of their industry and country. Still, the differences with native-born residents narrowed as migrants’ time living in the US increased.

Immigrants, especially those who have arrived in the US within the past five years, are more likely to be employed than their US-born peers, according to the 2025 Indeed Workforce Insights Report, a national population-weighted survey of more than 10,000 US residents. Immigrants’ optimism towards work and economic conditions is also more likely to be higher than their US counterparts — but only to a point. Over time, as immigrants face structural barriers, including language and cultural challenges and work authorization barriers, their optimism fades.

Almost two-thirds (65%) of working-age respondents born in the US reported being employed, compared to 83% of migrants who said they had moved to the country in the past five years. But interestingly, despite reporting high levels of employment, 30% of working-age respondents who have lived in the US for under five years also report that they are urgently and actively looking for paid employment; only 7% reported not seeking employment actively or passively. This is significantly less than those born in the country, 26% of whom indicated they are not looking for employment. Furthermore, working-age, foreign-born respondents who are currently employed full-time were nine percentage points more likely to be actively seeking jobs, potentially due to higher rates of underemployment or lower job stability due to work authorization issues.

This could also be an indication of the systemic lack of job satisfaction among immigrants, even those who have been here for a long time. Immigrants, regardless of how long they have been in the country, were uniformly more likely than their US-born peers to agree or strongly agree with the following statements:

- They are burned out by their work (42% vs 37%)

- Their work causes them a great deal of stress (39% vs 35%)

- Their work puts stress on their home life (36% vs 28%)

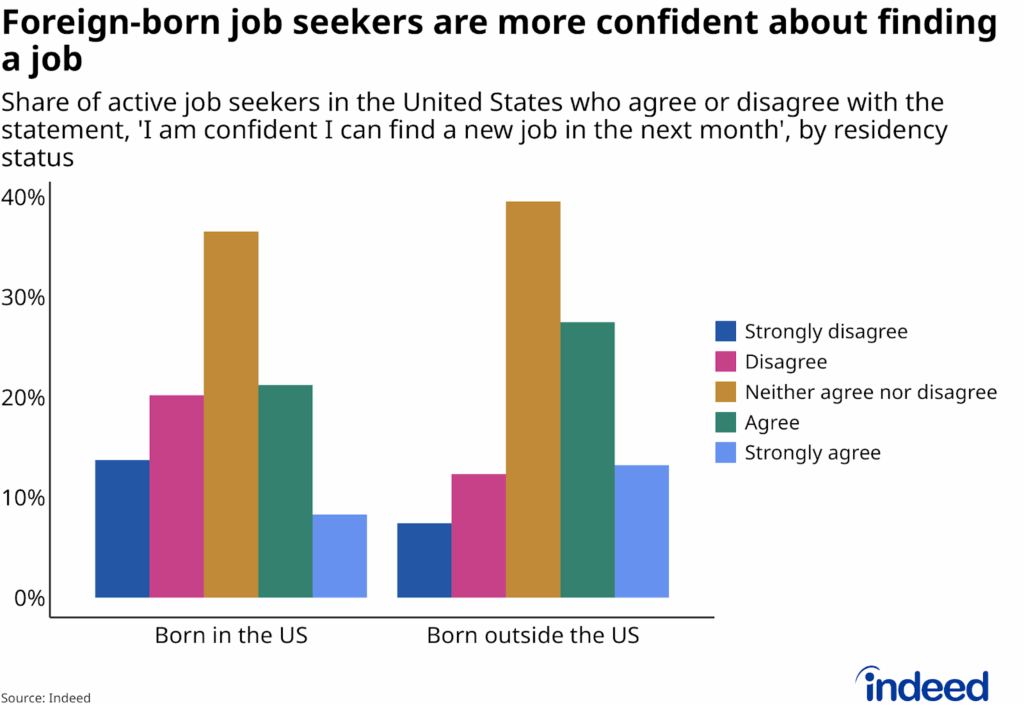

Interestingly, while employed migrants were less likely to say they feel secure in their current jobs, foreign-born job seekers were also more likely to express confidence in their ability to find a job quickly if needed. 39% of foreign-born respondents said they are somewhat or very concerned about their job security over the next 12 months, compared to 31% of native-born workers. This share was highest among recent migrants, with nearly half (49%) of them expressing concern about their job security.

However, the share of active job seekers born outside the US who said they agreed or strongly agreed that they were confident they could find a new job in the next month was 11 percentage points higher than the share of US-born workers who said the same.

Migrants in the United States (versus US-born workers) are more likely to agree or strongly agree with the following expectations about the next five years:

- More opportunity to get ahead and be more successful in my career (53% vs 42%)

- More upward mobility (49% vs 40%)

- Better work/life balance (54% vs 48%)

This optimism likely reflects not only confidence in the labor market but also a broader hope that conditions will improve as they integrate into life in the United States. The data also paints a nuanced picture of the migrant experience, wherein the hope for a better future is in tension with currently unstable situations.

Economic outlook

Foreign-born respondents were more likely to report a positive outlook for their industry’s labor market conditions in a year. Still, the discrepancy reduces as time living in the US increases. Roughly 40% of foreign-born respondents here for 10 years or less said they expect conditions in their industry to be better or much better in a year, far outpacing the share of similar native-born respondents that said the same. But among migrants here for more than a decade, just 28% said they expected conditions to be better in a year in their industry, similar to the US-born share (21%).

These trends differ by industry, however. In industries where migrants are overrepresented, such as industrial, manufacturing & technology, foreign-born workers were 22 percentage points more likely to report thinking their industry conditions would be worse or much worse over the next year compared to native-born workers. This could be because their overrepresentation in these industries gives them direct exposure to the slowing demand, and within these industries, they are more likely to take roles with higher layoff rates. For example, construction currently faces higher layoff rates than most industries, and migrants working in construction were 11 percentage points more likely to think their industry would be worse or much worse.

On the other hand, native-born workers in service roles — such as public sector & social services — were 10 percentage points more likely to report having a worse or much worse outlook of their industry one year down the line than migrants.

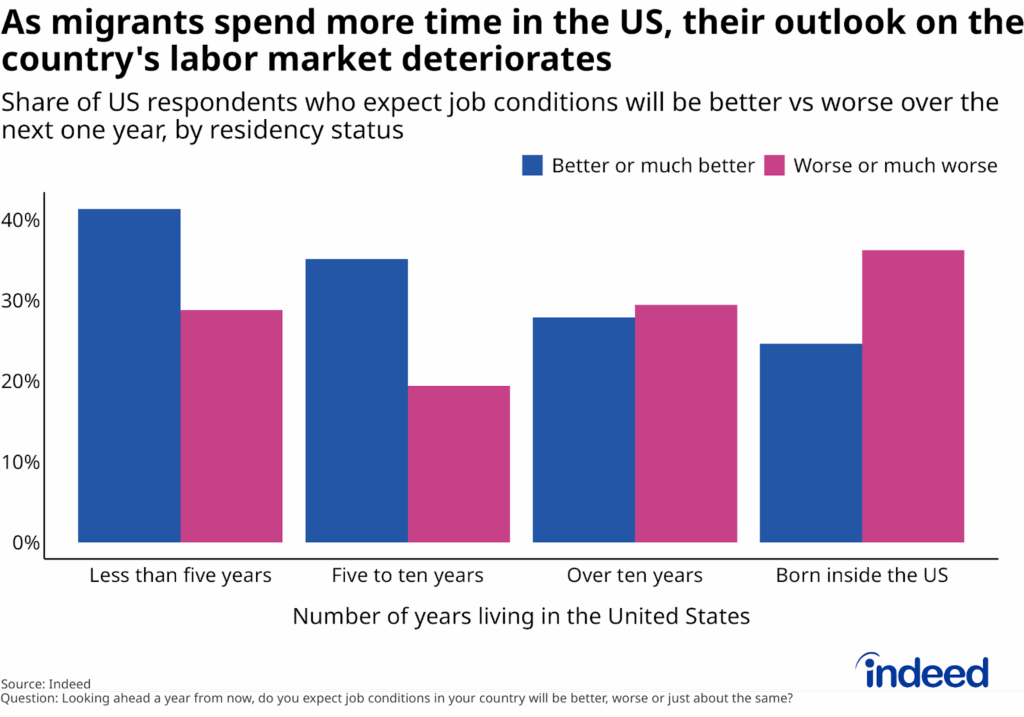

The same is true for broader labor market expectations. Foreign-born people are much more optimistic about job conditions compared to natives. Over 40% of migrants who have lived in the US for less than five years said they expect the overall labor market to improve over the next year, while only about 25% of US-born respondents shared that view. However, optimism declines as migrants spend more time in the country, converging toward the views of natives, and reverses after 10 years, with long-term migrants’ outlook turning more negative.

One possible interpretation is that newcomers who may not yet feel fully secure or satisfied in their current situation tend to look ahead with greater hope for improvement. Over time, however, this initial optimism gives way to a more tempered or even pessimistic view, as longer-term residents encounter the realities and structural challenges of the US labor market.

These barriers can include discrimination, credential recognition, and/or slower wage growth, all of which could dampen optimism over time.

Occupational barriers

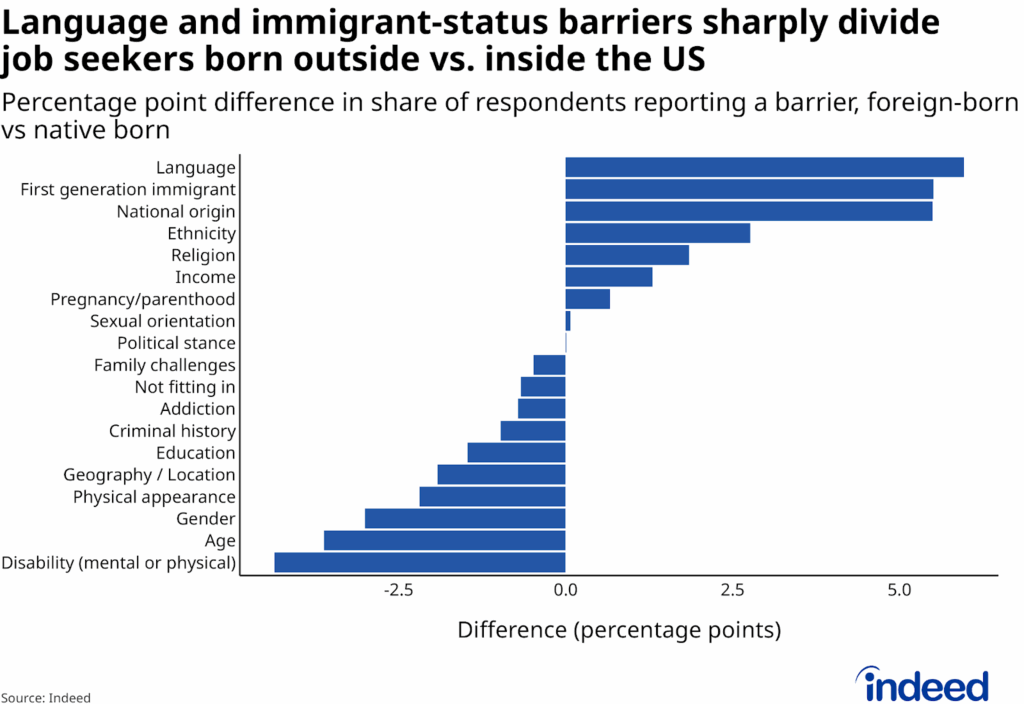

Foreign-born residents who are not employed face unique barriers compared to workers born in the US. They were more likely to note language, ethnicity, and religion as employment barriers, alongside their immigration status and national origin. Compared to native-born workers, they were significantly less likely to note barriers such as geography, gender, age, and disability.

Conclusion

While recent migrants in the United States display greater optimism about their future, this outlook often stands in contrast to current realities: foreign-born workers tend to report experiencing a less positive work culture and lower job security than native-born peers. Their initial elevated expectations may arise in part because of a lower “baseline,” and in part because ideals of the American Dream shape their optimism and belief in upward mobility and new opportunities, even if those promises are not always fully realized. For many, hopefulness reflects both a willingness to start from scratch and pursue long-term success, as well as an enduring faith that their risks and hard work will pay off in their new home, despite the challenges and setbacks they face along the way.

Methodology

This analysis utilizes data collected from an online survey, conducted for Indeed Hiring Lab by YouGov, across eight countries: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Fieldwork was conducted in May and June of 2025, with a total of n=80,936 interviews globally, and a minimum of n=10,000 interviews per market. This sample size provides a margin of error of ±1% at the 95% confidence level within each market.

For the United States, sampling was random and representative by age, gender, education, and region in all markets, and by race, aligned with the US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2022. Around 87% of respondents were born in the US, 11% were born abroad but had lived in the US for over 10 years, 1% had been born abroad and lived in the US for 5-10 years, and 1% had been born abroad and lived in the US for under 5 years. Working-age population refers to respondents who are between 18 and 64 years old.

Any percentage point differences referred to as “significant” in the text of this piece are statistically significant at the 10% level or better.