Key Points:

- US employers added 139,000 jobs in May and the unemployment rate stayed steady at 4.2%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Average hourly earnings rose by 3.9% year-over-year in May.

- Preliminary job growth from March and April was revised down by a combined 95,000 jobs.

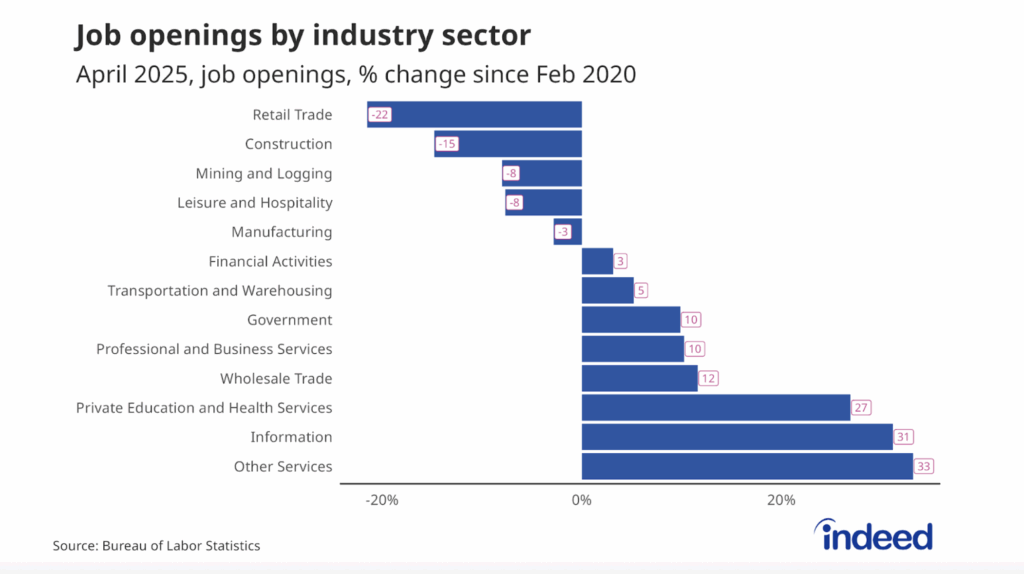

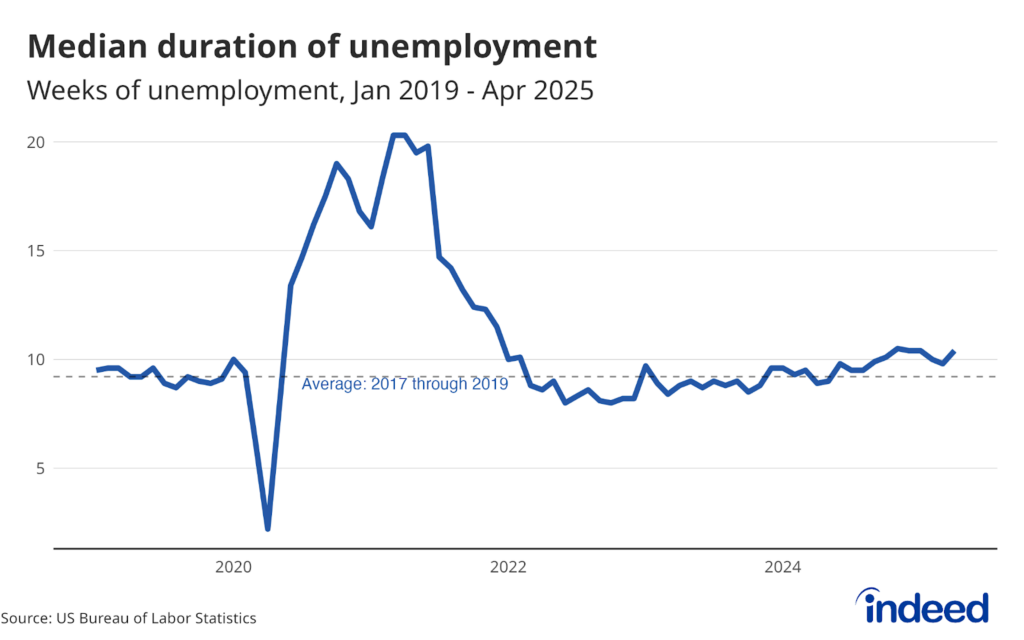

While the US job market continued to add a decent number of jobs in May, it’s notably cooler than it was even a few months ago, and continues to soften – to the point where there’s not much room for further slowdown before unemployment meaningfully starts to rise. And there are now clear trends in the data, not just vague signs, that even if the train is chugging forward, more and more people are getting left behind at the station. If you’re a doctor or a nurse or bartender, you’re probably feeling better in this environment than a software engineer or federal employee. Large downward revisions from prior months also took some of the shine off of unexpectedly strong data from earlier this year. This isn’t a bad report, per se, but there are clear signs of erosion just below the surface that may not be apparent just by looking only at the headline numbers.

Healthcare continued to lead job creation with 62,000 new positions, above the prior 12-month average of 44,000 jobs. Temporary help services, a bellwether industry for how employers feel about hiring, shed 20,000 jobs in May, a concerning sign of continued pullbacks in hiring. Federal employment continued to lose jobs in May, down 22,000 from the previous month. While the total loss in federal employment is below what some expected, the pace of decline has accelerated in recent reports and there are now 59,000 fewer federal workers than there were in January.

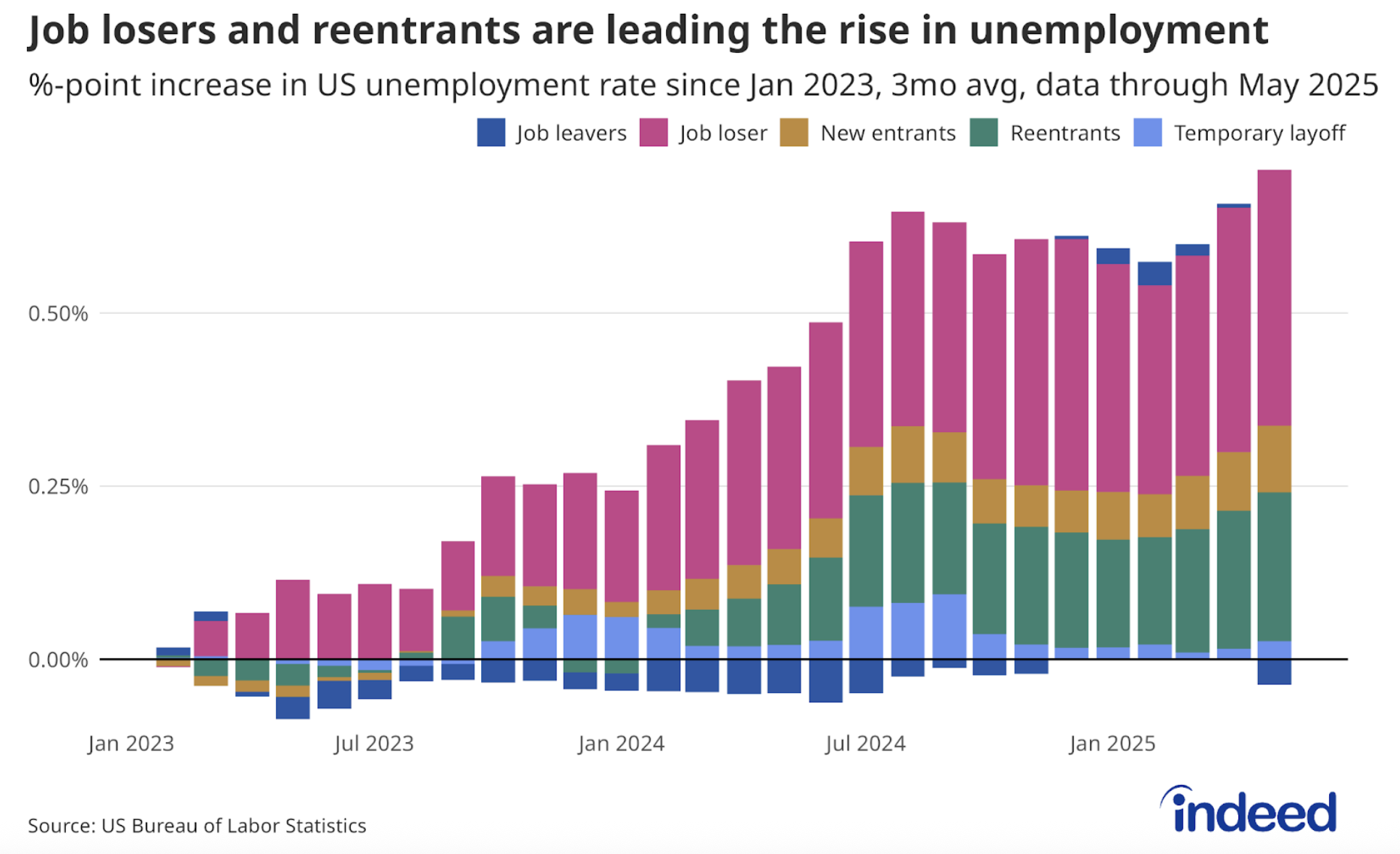

Those expecting some kind of dam burst or sudden reversal of ongoing trends would do well to recall Ernest Hemingway’s lessons about how bankruptcy happens: “Gradually, then all at once.” The steady erosion in the US job market cannot continue forever – at some point, there will just not be much left to give. In a low-hiring, slow-growth environment, employers can only hold onto their existing employees for so long before they too will have to be let go – increasing unemployment even as job opportunities continue to shrink.