Key points:

- Carer and aide, educator, and legal, social and welfare professions have outperformed other occupations in recent Australian episodes of economic weakness.

- Job losses for personal assistants and secretaries, machine operators and factory workers have been especially high during economic slumps.

- The COVID-19 crisis has been more severe than previous periods of economic weakness, with some occupations that normally hold up well devastated by lockdowns and other measures to control the epidemic.

The Australian economy hasn’t experienced a recession since the early 1990s. The COVID-19 crisis has brought an end to Australia’s record economic run, and that will have a profound and long-lasting impact on Australia’s job market.

During periods of economic weakness, some industries are typically more sensitive than others. For example, jobs in healthcare and education are more resilient in a slump than jobs for labourers or construction workers.

Using Australian Bureau of Statistics data, we examined which occupational groups held up best and worst during Australia’s last recession, which occurred in 1990-93, and the three extended periods of economic weakness since then (1996-97; 2008-09; 2013-14), which we call here slowdowns. A recession refers to a period of economic contraction, where output falls and unemployment rises. A slowdown is merely a prolonged period of slower-than-normal growth.

In this post, we refer to these four episodes collectively as ‘employment downturns’, which includes the three slowdowns, when employment grew less than 1% a year and the unemployment rate rose. We excluded particularly short slowdowns lasting three-to-four months, such as the brief 2000 and 2003 employment slumps.

While there is much to learn from these earlier episodes, the COVID-19 crisis is unique in many respects, particularly in its size and swiftness, the government-mandated lockdowns to control the epidemic and the economic support measures put in place. Some traditionally resilient industries have performed relatively well during the COVID-19 crisis, while others have been devastated.

Australia’s best-performing industries in a tough economy

Examining Australia’s last four employment downturns, we asked two questions to determine whether an occupation group performed strongly. First, did employment in the occupation increase or decrease? Second, did the occupation’s share of overall employment increase?

To rank occupation groups, we awarded one point each time a group registered rising employment and one point for increasing employment share. By taking each occupation’s average score for both of these measures, we determined which occupation groups performed best and worst in the four employment downturns. A perfect score of 4 means that both a group’s total employment and employment share rose in every downturn.

For example, to receive a perfect score in the 2013-14 slowdown, employment in an occupation would not only have to have been positive, but also have grown more than 1.1% throughout the 18-month period. By comparison, a perfect score in the recession is more difficult since occupation employment needed to have increased in an environment in which overall employment fell 2.7%.

Carer and aide, educator, and legal, social and welfare professional were the most resilient occupations in each of Australia’s last four employment downturns, with both employment and employment share increasing.

ICT professional also performed strongly during these periods. However, this occupation missed a perfect score because employment in it grew slower during the 2013-14 downturn than overall Australian employment.

Arts and media professional and sales assistant also rank highly. In each of Australia’s last four employment downturns, employment grew faster than the national average. However, employment fell in these occupations during the early 1990s recession, albeit to a lesser degree than jobs in the economy as a whole.

The 13 occupations in the table below, which represent around 30% of all occupation groups and accounted for 43% of Australian employment in 2019, all had scores of at least 3.

Occupations that are resilient in a weak economy have several things in common. Services that are commonly non-discretionary, such as education, healthcare and legal services, tend to outperform in an employment downturn. In addition, education, healthcare and care giving are financed primarily by federal and state governments, providing some insulation from market forces.

More generally, professional occupations outperform in a weak economy, a timely reminder that the burden of an employment downturn often falls disproportionately on people with less education and lower incomes.

Office and blue-collar occupations perform worst in a tough economy

Over the past three decades, six occupation groups received a score of zero. They can be separated into two main groups: office support workers and labourers/factory workers.

The personal assistant, secretary, clerical worker and support staff occupations have generally performed poorly during employment downturns, even mild ones. And a weak economy often hits manufacturing and production hard as well, slashing demand for labourers, factory process workers and machinery and stationary plant operators.

These occupations have steadily declined as a share of total employment over several decades. Technology has reduced the need for administrative staff. And the Australian economy has moved away from manufacturing and production in favour of services. Episodes of economic weakness may simply have sped up a decline already under way.

One group that stands out is CEOs and general managers. Those in charge often find themselves on the chopping block in a tough economy, either due to higher levels of business failure or because they are blamed for poor business performance.

These 13 occupations, each with a maximum employment downturn score of 1 out of 5, accounted for almost a quarter of Australian employment in 2019. Around 30% of occupation groups received a score of 1 or lower.

Why is the COVID-19 crisis different?

The COVID-19 crisis is unprecedented in size and swiftness. In just two months, April and May, Australian employment fell 872,000, or 6.7%. By comparison, in Australia’s recession of the early 1990s, employment fell 3.6% over 31 months. This time, many jobs have been sacrificed via lockdowns on economic activity and social distancing, in stark contrast to other employment downturns Australia has experienced.

The COVID-19 impact on jobs could very well be different from previous employment downturns. Occupations in areas such as hospitality, entertainment and sport — normally solid performers in a tough economy — have been devastated amid shuttered restaurants, theatres and sporting venues.

The effects of COVID-19 may also be more volatile than those of a normal employment downturn, depending on what kinds of restrictions are in place and when they are lifted. Government intervention has distorted the market forces that typically drive employment trends during periods of economic weakness. Changes in government policy and the introduction and removal of stimulus or support measures could play a big role in job creation during and after the COVID-19 crisis.

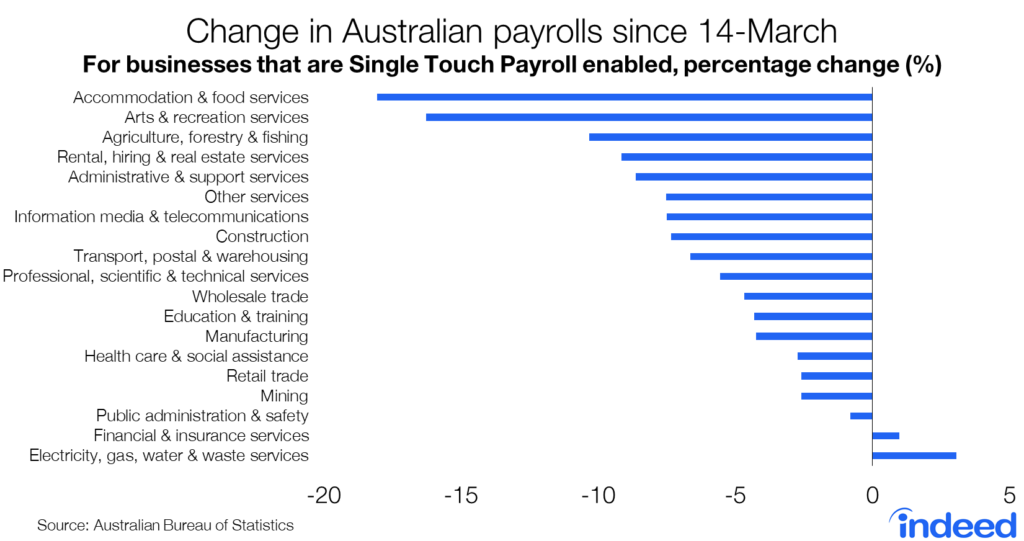

Focusing on industry payrolls, which measure jobs by industry rather than by occupation, also shows how unique the current crisis is. Only two industries, finance and insurance and utilities, have higher payrolls now than before the crisis.

Employment fell everywhere else. Between 14 March and 11 July, payrolls plunged 18% in accommodation and food services and 16% in arts and recreation. Jobs in these industries traditionally hold up well during employment downturns.

Other normally resilient industries, such as education and healthcare, have done better. The factors that drive employment in these areas, such as public spending and demographic trends, have remained in place despite widespread lockdowns. However, education has experienced considerable uncertainty, particularly around school openings, that is unlike a normal employment downturn.

Construction, normally an underperformer in a tough economy, held up surprisingly well early in the crisis. Construction was largely untouched by restrictions in economic activity. However, unlike most other sectors, employment continued to decline through June and into July.

Historically, around 30% of Australian sectors have performed well under tough economic conditions. This time though, employment has fallen more sharply and rapidly than in previous recessions. Government-mandated lockdowns and support measures have played an important role in both job losses and creation.

Yet even in this most difficult of circumstances, some industries are proving more resilient than others. The utilities industry has performed strongly, showing that employment in essential services offers a high degree of job security during this crisis. Meanwhile, there is also greater employment in finance and insurance than there was pre-crisis.

As the economy emerges from lockdown, employment trends will evolve. Will the labour market begin to look more the way it does in a normal recession? Or will the impact of COVID-19 leave scars that will take a long time to heal?

Methodology:

An employment downturn was defined as a period when employment contracts or grows less than 1% a year and the unemployment rate rises. Falling labour force participation was considered as a cross-check. We examined employment slowdowns in addition to recessions because Australia has had only one recession over the past three decades. In addition, occupational group data from before 1986 are limited. Particularly short downturns, such as those in 2000 and 2003, were excluded.

The employment downturn score was calculated by measuring how each occupation group performed in an employment downturn. If employment in an occupation increased in all four employment downturns, then that occupation received a score of 4. Similarly, if an occupation’s employment share rose in all 4 employment downturns then that occupation received a score of 4. The average of these measures was used to calculate a final score.

The analysis of business payrolls involves broader industry categories than does the occupational employment analysis due to limitations arising from the recent creation of business payroll data to measure the labour market impact of COVID-19. Data on industry group employment won’t be available until 25 June 2020.