Key points:

- Part-time work has dominated job growth in Australia since the onset of the global financial crisis more than a decade ago.

- While some of this is desirable, likely reflecting greater demand for work-life balance, the increase in part-time employment is overwhelmingly due to a weak economy that has failed to create enough full-time jobs.

- Part-time work has been forced on Australian workers, primarily younger workers aged 15-24, with almost every industry relying more heavily on part-timers than they were a decade ago.

In Australia, half of all employment growth over the past decade has been of the part-time variety. Of course, work-life balance and flexibility are increasingly important to many workers. Yet working part-time isn’t always a choice. Weak economic conditions have forced thousands of workers, typically younger ones, into part-time roles even though they want to work full-time.

On the plus side, workplace flexibility has created a more inclusive labour force, allowing thousands of women and older Australians to join the workforce. Women in particular benefit from part-time and flexible working arrangements after childbirth, when it may be difficult to handle a full-time schedule. And older workers, instead of going cold turkey as they transition to retirement, often choose to shift to a part-time schedule.

Full-time workers may also be benefiting from a better work-life balance. Fewer Australians are working overly long hours. Average full-time hours are declining as excessive hours become less common. And fewer workers say they are overworked. That means not just more time to spend with family and friends—it lowers stress and improves mental health.

Unfortunately, fewer hours and increased part-time work haven’t been a boon for everyone. In fact, some of those working part-time are doing so involuntarily. A troubled economy over the past decade has forced many Australians into part-time roles they may not want. This is particularly true for younger workers. For example, around three-quarters of the rise in part-time work among younger workers aged 15-24 reflects weak economic conditions rather than a preference for part-time work over the past decade. One saving grace—part-time workers are working longer hours than in the past.

Analysing data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), we found:

- Both younger workers and older workers have a stronger preference for part-time employment now compared with a decade ago, perhaps reflecting a greater desire for workplace flexibility and work-life balance.

- Nevertheless, the main driver of rising part-time employment has been subpar economic conditions, which have forced many Australian workers into part-time or insecure work.

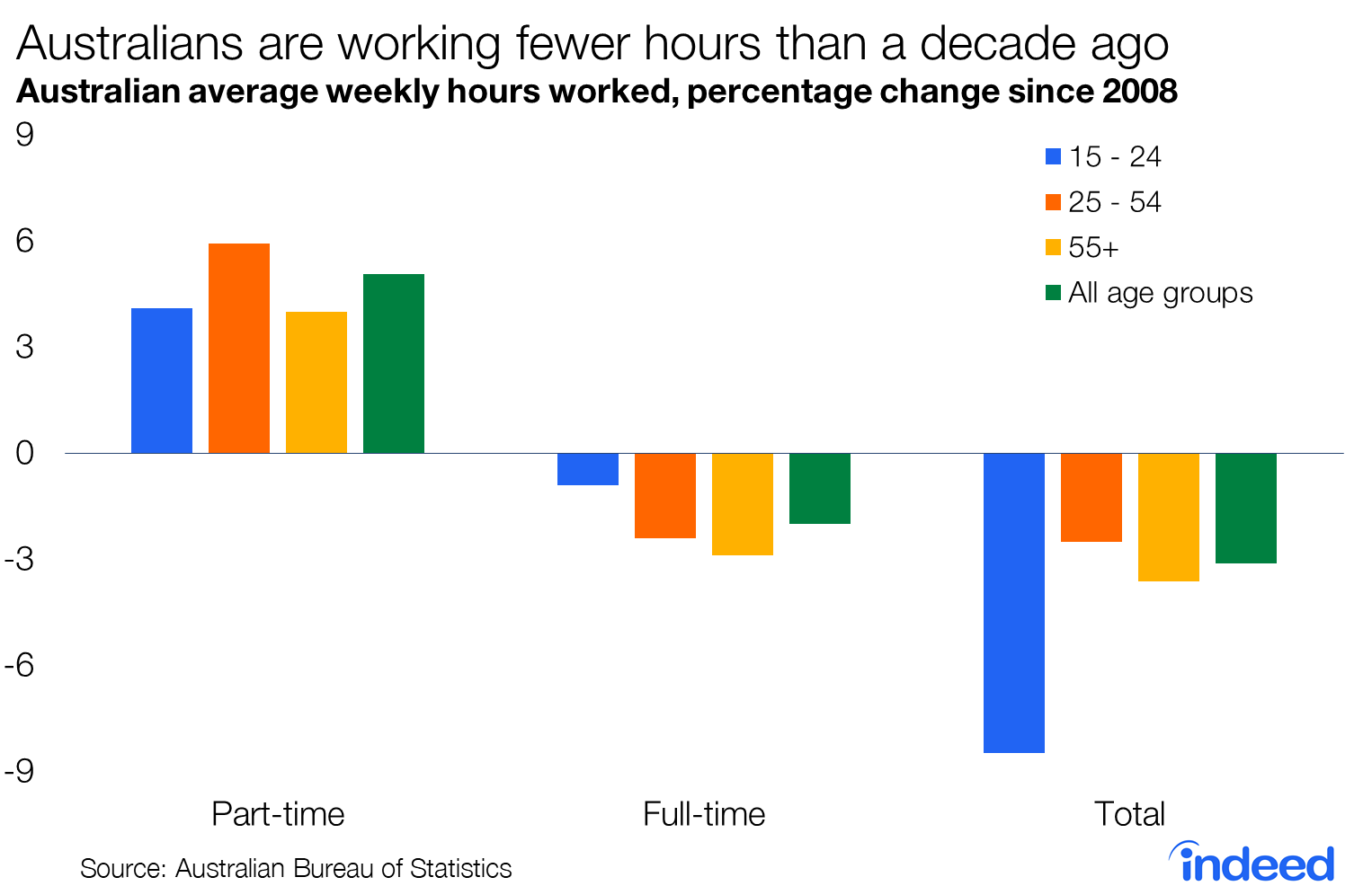

- Some of this damage has been offset by longer hours for part-time employees. Average weekly hours worked by part-time employees have increased 5% over the past decade.

- Almost every industry and occupation is relying on part-time workers more than in the past. This is particularly evident in youth-oriented industries such as retail and hospitality.

The average Australian is working fewer hours

Amid the shift toward greater part-time employment, average hours worked by Australian employees has declined 3% over the past decade. But the trends among part-time and full-time workers are distinct. Part-time employees on average are working 5% more hours per week. At the same time, full-time employees are working 2% fewer hours.

These patterns are apparent across all age groups but have been particularly dramatic for younger workers aged 15-24. For these workers, average weekly hours are down 8.5% over the past decade, driven largely by a sharp rise in part-time employment.

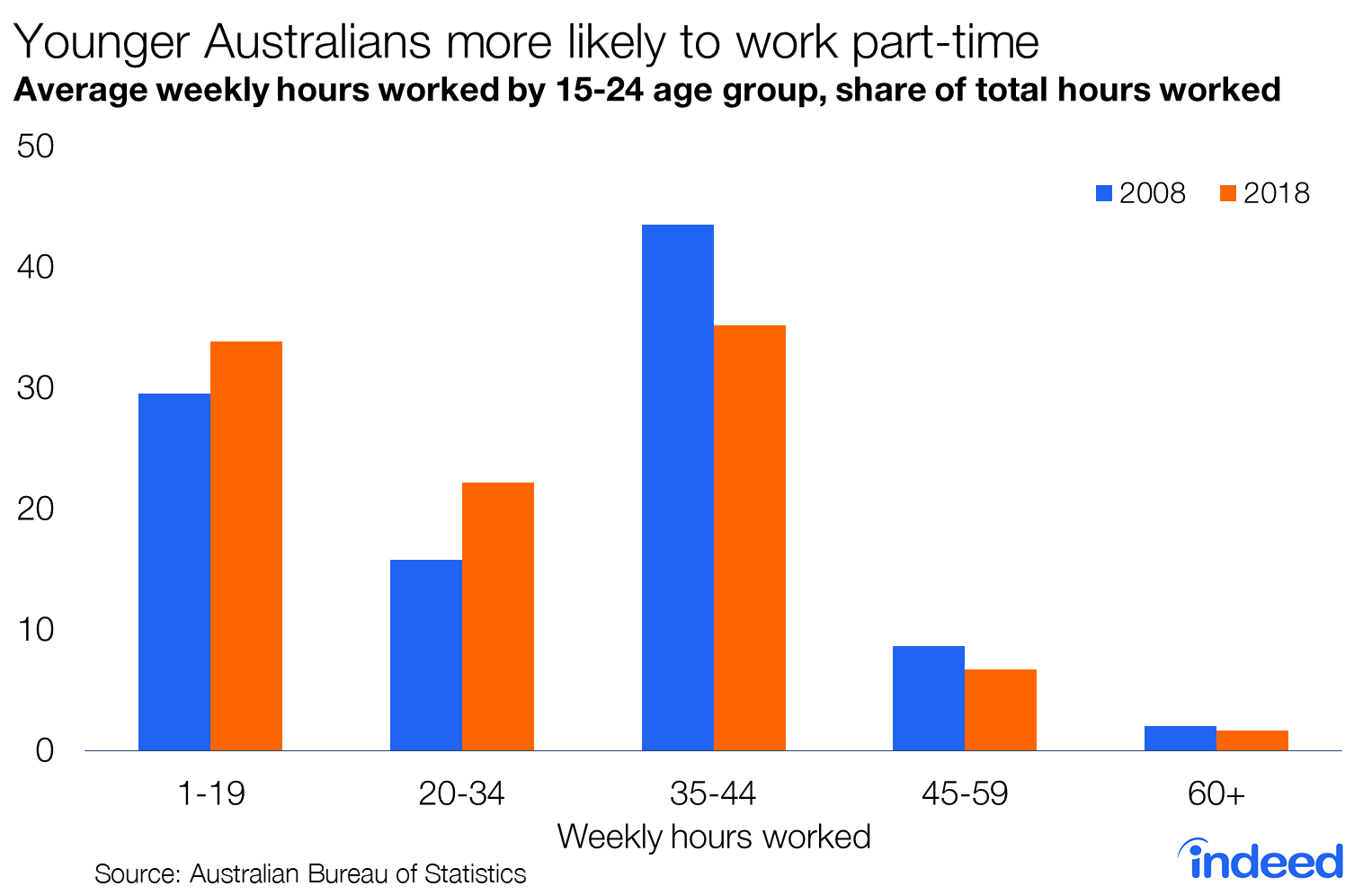

Younger employees are clustered in two distinct groups. Around 56% are working fewer than 35 hours a week, a group largely composed of students combining work and study. A 35 hour work week is the conventional dividing line between full-time and part-time work. Another 35% are working 35 to 44 hours a week. By comparison, just 45% of younger Australians worked part-time a decade ago.

While the shift among younger workers may partly reflect greater interest in university education, the job-market experiences of young Australians have overall been poor. Almost 18% of younger workers consider themselves underemployed, working part-time but preferring to work longer hours, compared with 11% a decade ago. To the degree that this shift toward part-time employment has been forced, it has disproportionately affected younger employees. Indeed, the part-time employment share among workers over 34 has increased only modestly. And many of those workers may have benefited from no longer working excessive hours.

Part-time work is involuntary for some workers

While some workers choose to work fewer hours, others have no choice about a reduced work schedule. In Australia, involuntary part-time work has driven the strong growth in this category of employment over the past decade.

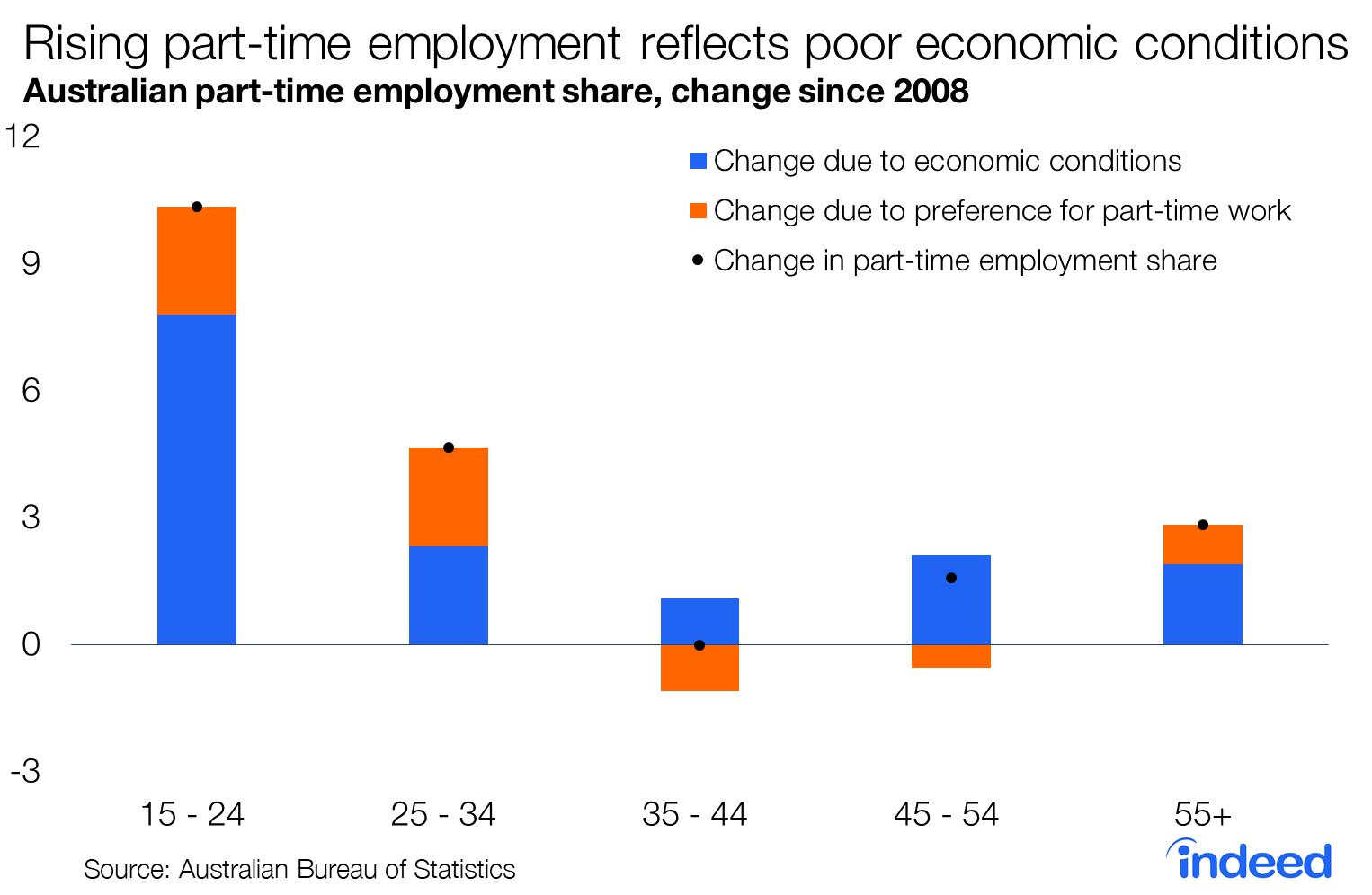

Since 2008, poor economic conditions explain around three-quarters of the increase in the part-time employment share among workers aged 15-24, according to calculations derived from ABS data. A lackluster economy helps explain half of the part-time increase among workers aged 25-34 and almost two-thirds among workers over 55. The remainder represents an increased preference for part-time work—probably due to a combination of study and childcare for younger workers and a transition toward retirement for older workers.

Underemployment among Australian workers in the 35-44 and 45-54 age groups has increased noticeably despite a relatively small increase in their part-time employment share. Workers in these age groups often have school-age children and hefty mortgages and want safe, secure, and full-time work. Their preference for longer hours has increased over the past decade, perhaps because of stagnating wages and rising mortgage debt.

Although younger and older workers increasingly prefer part-time hours, which may be due to the benefits of flexibility and work-life balance, this isn’t the primary driver of part-time employment. This is overwhelmingly an economic story, with weak conditions forcing thousands of Australians into part-time and often insecure work.

Almost every industry and occupation is employing more part-time workers

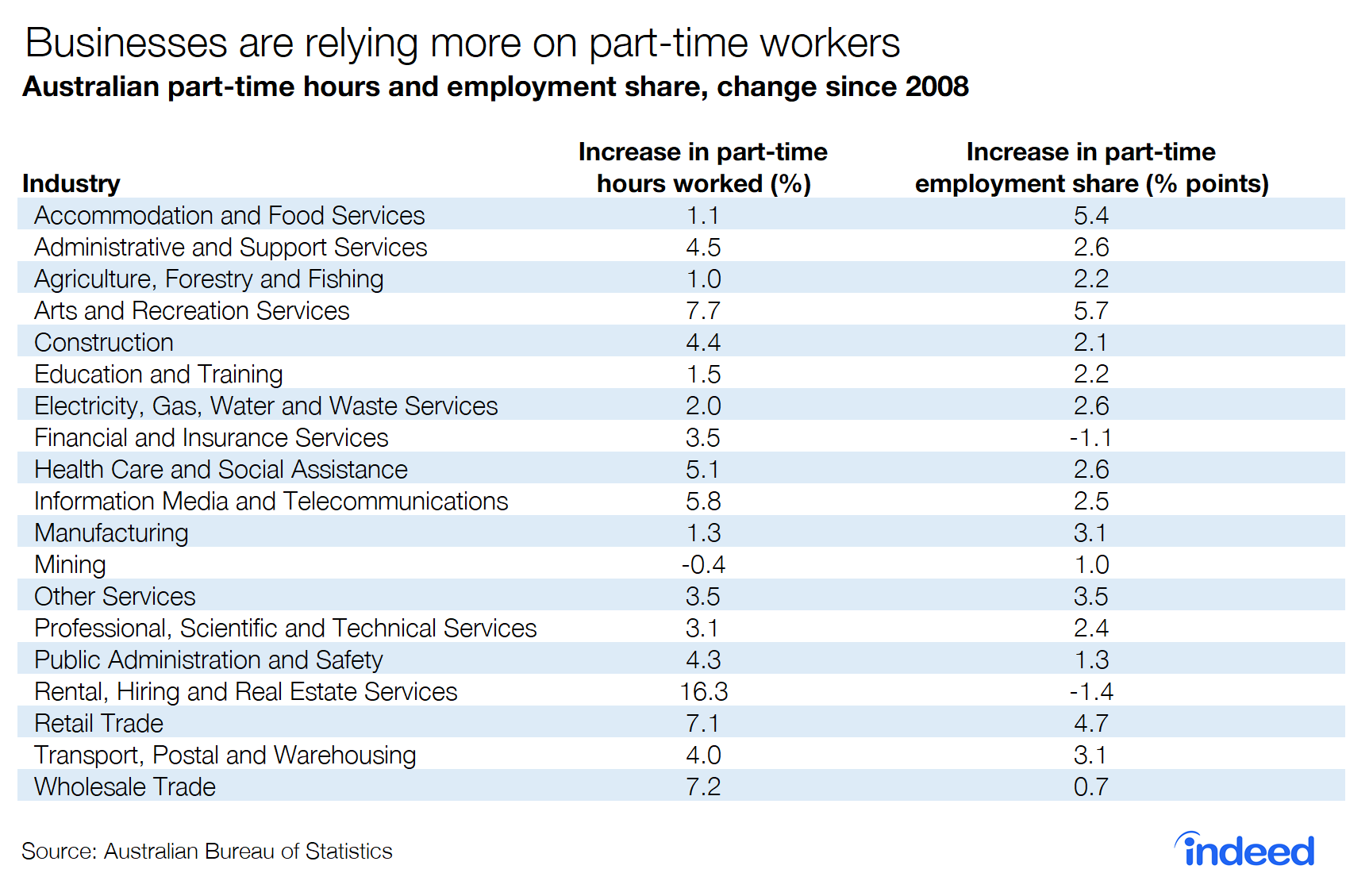

Businesses across the country are relying more heavily on part-time workers, even those not normally associated with the practice. The part-time employment share is rising in all but two industries—finance and real estate. The increase has been led by two industries long associated with part-time or casual work—retail and hospitality. In the accommodation and food services industries, 60% of workers are employed part-time, up from 55% a decade ago. And around 51% of retail workers are employed part-time, rising from about 46%.

At the same time, the number of hours worked by part-timers has risen. Only in one industry—mining—are part-time workers working fewer hours on average than a decade ago. In other industries, the part-time gains have been huge. For example, in real estate, part-timers are working 16% more hours than a decade ago. Part-time hours in arts and recreation, wholesale trade, and retail trade are all over 7% higher.

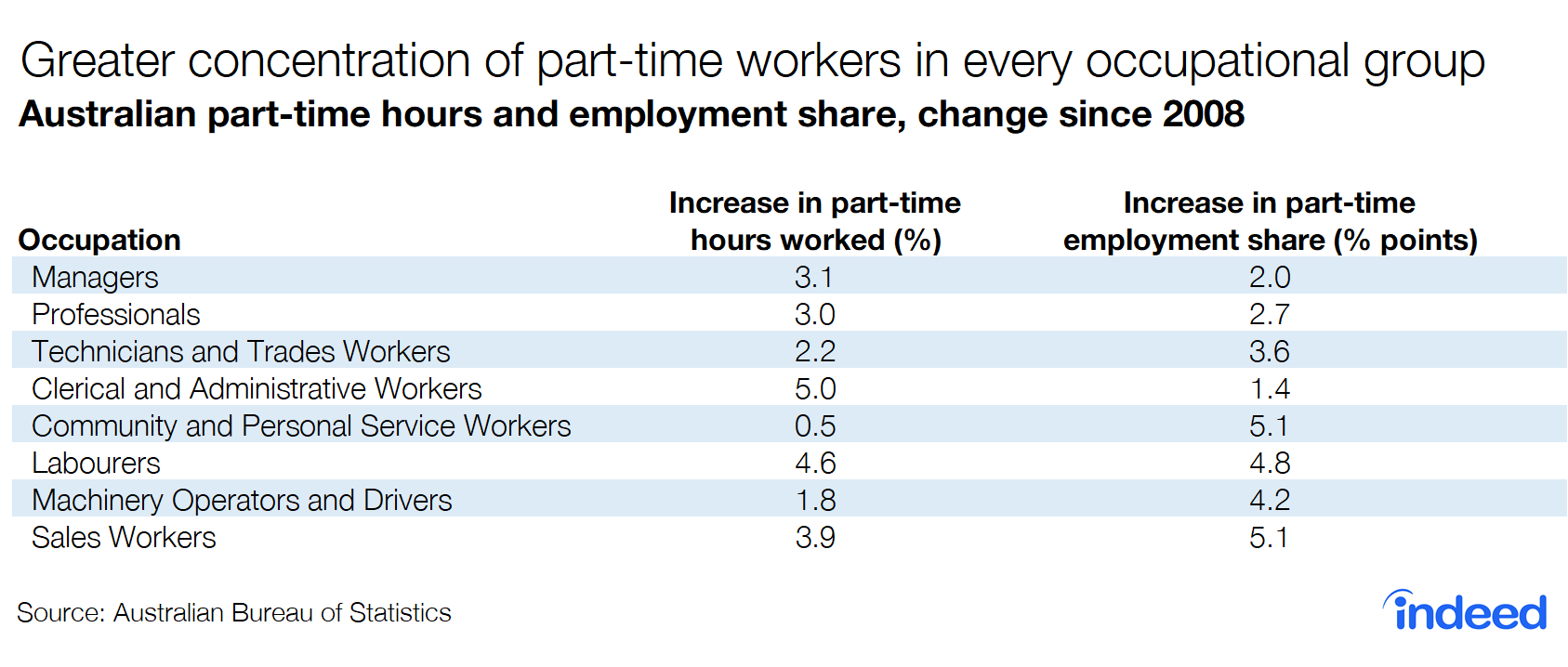

Looking at occupation rather than industry yields a similar result. Every occupational group has experienced an increase in part-time employment share and average hours worked by part-time employees.

The rise in part-time employment share has been most pronounced among sales and community workers, both up around 5 percentage points. Part-time workers are also increasingly used in traditional blue-collar occupations, such as labourer and machinery operator. Even occupations where part-timers are not typically found, such as managers, are increasingly going part-time.

Although the shift towards greater part-time employment is widespread across industries and occupations, it is still concentrated among younger workers. This group has seen a sharp increase in part-time employment share since the onset of the global financial crisis more than a decade ago. Younger workers face an economy in which jobs increasingly are part-time and insecure, regardless of industry or occupation. Over the past two years, Australia’s labour market has started to create more full-time opportunities and that may help reverse the long-term trend toward part-time and insecure work. Full-time hours and more job security in a tighter labour market would be a great boon to job seekers.

Some workers have benefited from fewer hours

Part-time schedules are a benefit for some workers and a detriment to others. But for those working full-time, there is a clear good news story—a steady decline in the number of Australians who say they are overworked. Today’s greater emphasis on work-life balance and flexible working arrangements represents a shift from long, and often unhealthy, work schedules.

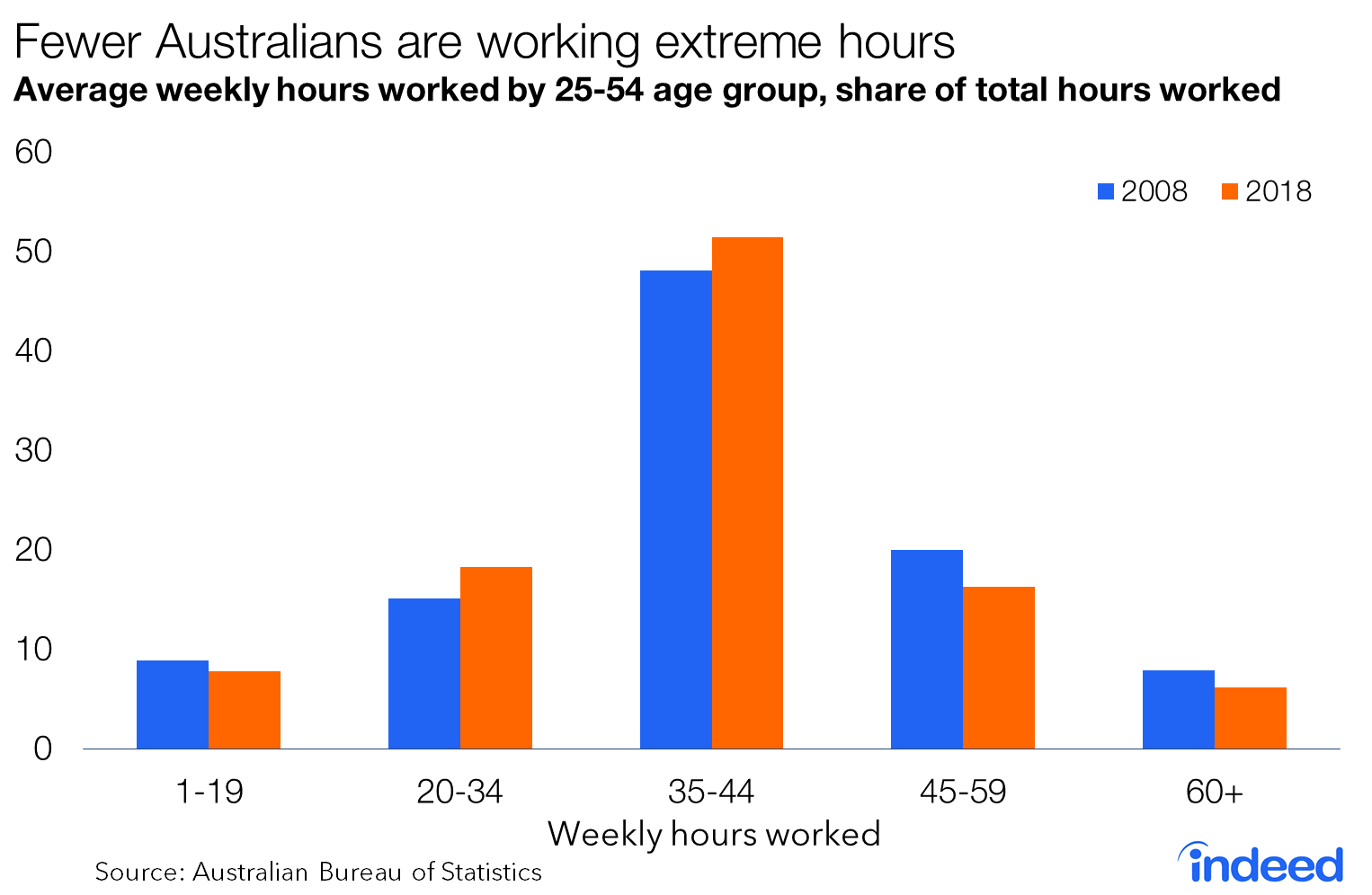

Currently around half of all employees aged 25-54 work a typical full-time schedule of 35 to 44 hours per week. Surprisingly, this is higher than a decade ago despite the increase in part-time work and illustrates an important overall trend: workers today are less likely to labor excessive hours. In 2018, around 23% of employees worked longer than 44 hours a week, down from 28% a decade ago.

In other words, Australian employers are not simply paying lip service to work-life balance. It is reflected in the demands they place on staff and the hours they expect them to work. Full-time workers across the board are shifting toward fewer hours. In 2015, 23.7% of men and 22.4% of women considered themselves overworked, according to the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia’ Survey, down from 27.6% of men and 25.3% of women in 2008.

Nevertheless, employers shouldn’t pat themselves on the back. Australia still ranks poorly among OECD countries in excessive hours of work and amount of leisure time. Keeping up with our global peers will require an even greater commitment to flexibility and work-life balance. The great challenge for Australian employers is achieving that without creating an army of workers dissatisfied with their hours and lack of job security. That balance hasn’t yet been reached—not by a long shot—particularly among younger workers.