Key points:

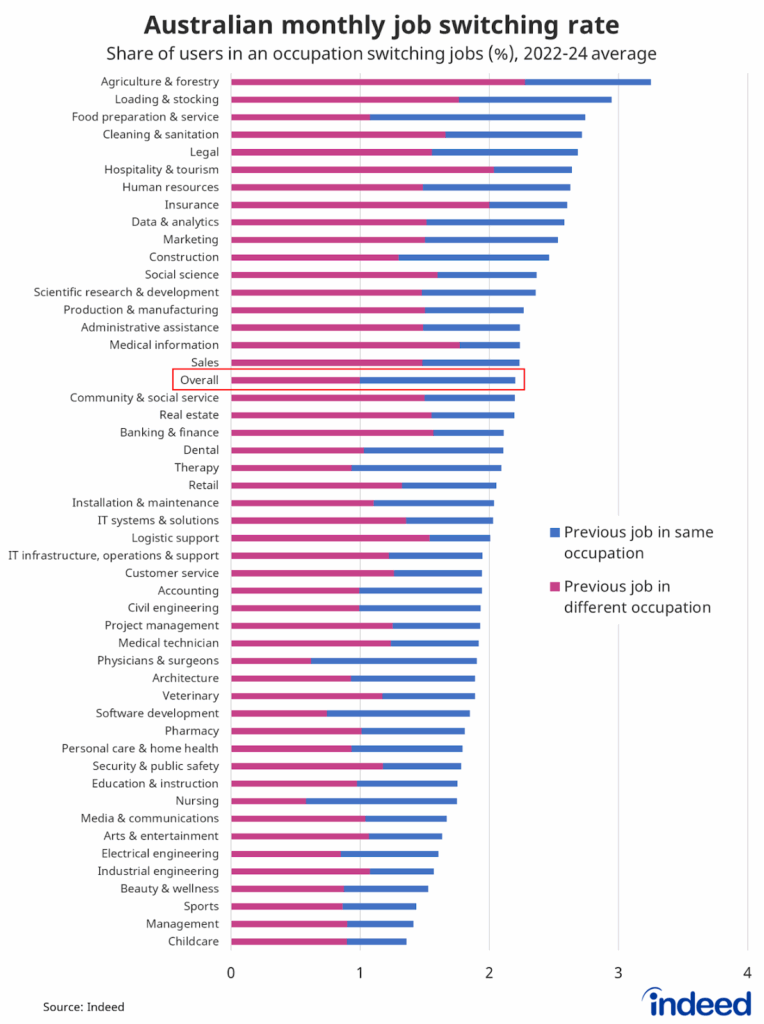

- Job switching is most common in occupations such as agriculture & forestry, loading & stocking and food preparation & service. By contrast, it tends to be lowest in childcare, management and sports occupations.

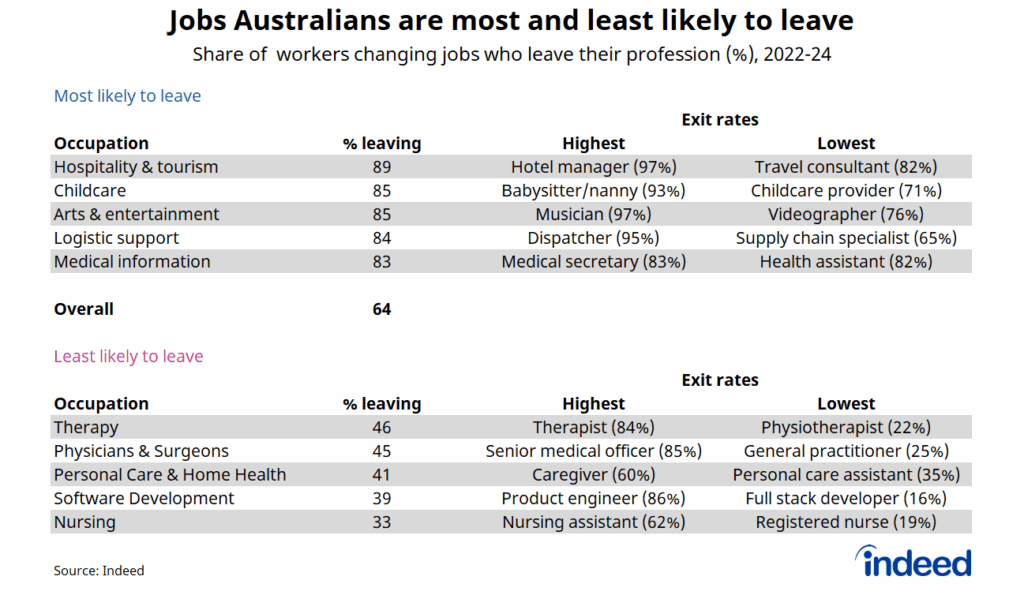

- Workers in nursing, software development, personal care & home health and physicians & surgeons are the least likely to leave their professions.

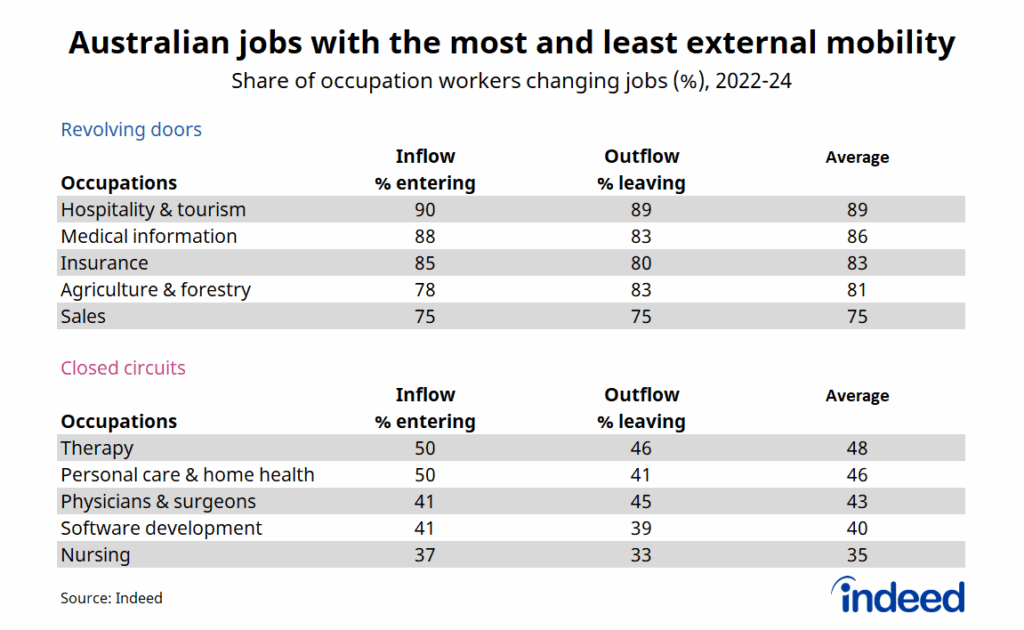

- Occupations such as nursing, physicians & surgeons and software development operate as ‘closed circuits’: they rarely attract outside talent, but also rarely lose workers to other occupations. Others, such as hospitality & tourism, are more of a ‘revolving door’ where large numbers of workers enter and leave the occupation regularly.

For more information, check out our companion piece to this analysis, with interactive diagrams and downloadable charts.

Australians change jobs for many reasons. Higher pay or career advancement are obvious motivations. Some jobseekers might want to reduce stress, improve job security or enjoy greater work-life balance. Others might be motivated by a bad experience in their current job or external factors, such as redundancy, health or relocation.

Around 1.1 million Australians changed jobs over the past year, according to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, with a total of 2.4 million starting their current job. Around 680,000 Australian workers changed their career path, leaving their previous occupational category, with two-thirds achieving that via changing employers (the remainder found new opportunities internally).

Using Indeed’s data, we tracked career pathways based on the jobs that users record on their resumes, identifying where talent comes from and where it goes. Every month, around 1 in 45 Australian users on Indeed with an uploaded resume change jobs. Some occupations find it much easier than others to attract external talent. Similarly, workers are more loyal to some occupations than to others. Both of these trends highlight that Australian job switching trends are similar to those in the United States.

An important caveat to this research is that job switching rates are likely to be higher on Indeed than in reality since Indeed is a job matching platform. Users looking for a new job are more likely to engage with the website compared to those happily employed.

Occupations where job switching is most and least common

Between 2022 and 2024, around 2.2% of Indeed users in Australia (1 in 45) switched into a new job every month. Yet job switching rates varied considerably across occupations.

New entrants were most common in agriculture & forestry, where around 3.3% of workers switch into a new job every month. The switching rate was also elevated in loading & stocking and food preparation & service. More frequent job switching likely reflects a combination of lower pay and a larger share of entry-level jobs. These jobs are often viewed as a stepping stone in a person’s career and typically attract younger candidates who have higher job mobility.

By comparison, greater workforce stability is typically found in occupations such as childcare, management and sports where users are less active. In these three occupations, just 1.4% of workers switched jobs in the average month, more than a third below the national average.

Overall, around two-thirds of occupational categories had a job switching rate below the national average.

Some occupations also prove more attractive or accessible to outside talent. Agriculture & forestry, hospitality & tourism and insurance, for example, all attract a high volume of job switches from external jobseekers. That’s also the case for medical information and loading & stocking occupations.

These roles often have lower barriers to entry or involve more generalised skill sets that overlap with other occupations. This allows for easier career transitions than roles such as nursing, physicians & surgeons and software development, which involve more specialised skill sets or extensive education and training.

The jobs that Australians don’t want to leave

Some jobs also seem to inspire greater loyalty than others or are simply more difficult to leave. This could be due to work-life balance, pay and conditions, passion for the work or even just an unwillingness to ‘waste’ your education by moving on.

From 2022 to 2024, nursing was the occupation category that workers were least likely to leave when taking on a new job, with just one-third of job switchers leaving the profession. Within the nursing profession though, the likelihood of leaving varies considerably, from 62% for nursing assistants to 19% for registered nurses.

The leaving rate was also low in software development (39% of job leavers left the profession), personal care & home health (41%), physicians & surgeons (45%) and therapy (46%). There is a clear healthcare theme among those most loyal to their profession.

A common, though not universal, thread among these occupations is a high barrier to entry, with workers needing to gain considerable experience, education, qualifications and training in order to enter the profession. That long-term commitment might signal the passion that these workers have for their chosen career, the sacrifices that they have made or even that they don’t want to ‘waste’ that investment by leaving the industry.

At the other end of the spectrum are occupations that people often treat as a short-term rental rather than somewhere they plan to stay. In hospitality & tourism, 89% of job leavers from 2022 to 2024 left the profession, ahead of childcare (85%), arts & entertainment (85%), logistic support (84%) and medical information (83%).

Many of the roles within these categories are junior or entry-level positions. Working in hospitality is often the first job for many young Australians, but rarely where they stay long-term. Within arts & entertainment, around 97% of musicians who change jobs leave the profession, perhaps because their dream to “make it big” was never realised.

Closed circuits versus revolving door

Looking at entry and exit rates (along with the overall volume of job switches) reveals two distinct patterns: some occupations are ‘closed circuits’ where it is difficult to enter but also rare to leave, while others resemble a ‘revolving door’ that attracts a lot of talent from elsewhere, but that talent doesn’t stick around for long.

Nursing and physicians & surgeons are clear examples of closed circuits, and the job switching rates in these occupations are well below the national average. These roles attract relatively little outside talent, with new entrants requiring extensive education and a specialised skill-set before entering the healthcare sector. But on the flip side, they also lose relatively little talent. Other healthcare professions, such as personal care & home health and therapy, exhibit the same trends.

The tech sector is another one with high barriers to entry, limiting who can enter the profession. However, once you’ve experienced tech salaries, it’s often hard to leave.

By contrast, hospitality & tourism, medical information, insurance, agriculture & forestry and sales all exemplify revolving-door occupations. Job switching rates are high — well above the national average — with the occupations attracting plenty of external jobseekers. However, they are also losing a lot of workers to other professions.

Conclusion

Job mobility varies considerably across the Australian job market and that can have real implications for recruitment and staff retention. While around 2.2% of Indeed users change jobs in an average month, that number ranges from 3.3% of users in agriculture & forestry and 1.4% in childcare.

High-turnover jobs often serve as entry points for junior workers, providing valuable work experience, but retaining those staff is often difficult. Low-turnover jobs face a different challenge: attracting outside talent is harder, making training and development crucial to filling roles when vacancies arise.

Ultimately, retention is much easier in some occupations than in others. Nurses, doctors, chefs and tech workers may change employers, pursuing better conditions or greater opportunities, but they rarely leave the profession altogether.

Methodology

We identify job switches based on the start and end dates of work experiences communicated on individual resumes. We limit our analysis to profiles in which the job start and end dates include the year and the month, rather than only the year. We focus on the 2022–2024 post-pandemic period.

A job switch is any job start preceded by another work experience. We define the job switch rate as the ratio of the number of job experiences starting in month t that were preceded by other job experiences on the resume, divided by the total number of job experiences in the dataset that include month t. The occupation switch rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of job experiences starting in month t, with previous experience in a different occupation, divided by the total number of job experiences in the dataset that include month t.

The occupational exit rate among job switchers is calculated as the ratio of the number of experiences in category i, which are followed by a job experience in a different category during period t, divided by the total number of experiences in category i that precede a job experience in period t. The calculation is based on switches from one stable job to another (>6 months tenure in both jobs) to avoid capturing seasonal jobs or internships, with a maximum gap of 6 months in between.

If the occupational exit rates of job switchers appear high, there are a few important caveats to remember. First, since Indeed is a job matching platform, individuals in long-term, stable employment relationships who don’t actively search for jobs are less likely to be represented in our data. Second, resume-writing conventions may differ across occupations and job types, affecting how experiences are reported. For instance, self-employment and freelance work may be reported by summarizing multiple short-term engagements under a single, continuous role, only distinguishing a new experience if it represents a significant shift. Third, some occupational categories — such as management or administrative assistance — are more likely to attract talent from a broad range of occupations. This can inflate apparent switching rates into and out of those roles.